Why Thousands of Chhattisgarh Adivasis Protested This Forest Officer’s Transfer

“In these parts, a forest officer is considered a big deal and often seen as unapproachable to the common people. But DFO Dhammshil would walk and cycle into the jungle, meet people there, explain government schemes to them and emphasise that this jungle belongs to them, and not the government.”

When Ganveer Dhammshil, former divisional forest officer (DFO) of Keshkal division in Kondagaon district, Chhattisgarh, was transferred out earlier this month, thousands from different tribal communities came out in protest against the local MLA who engineered the move. The matter had reached Chief Minister Bhupesh Bhagel’s office.

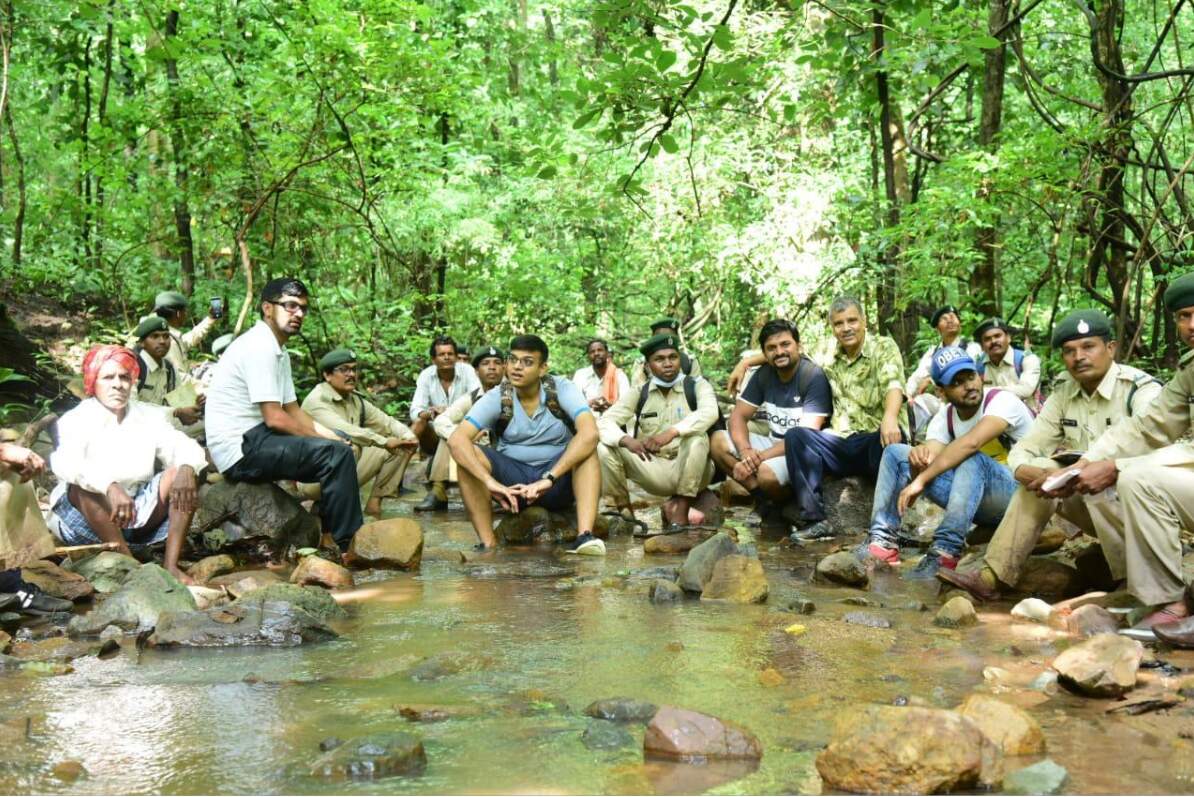

“Everyone here is devastated about his transfer. He was the first officer to genuinely address those of us at the grassroots. He would walk, cycle or trek and visit our villages deep in the jungle. While addressing us, he would sit with the common people on the ground instead of a chair, and listen to us. More importantly, he helped us understand our rights as forest dwelling people, what we can do with the resources at our disposal, and how to strengthen our livelihoods. He ensured that all our work with the forest department was conducted with the utmost transparency,” says Parshuram Salam, a resident of Themli village and member of the local Joint Forest Management Committee.

Krishna Dutt Upadhyaya, a 65-year-old journalist and social activist from Keshkal tehsil, who has covered events here for the past four decades, also agrees.

“I have seen such an honest officer in the forest department for the first time in my life. A man with genuine passion for the people, he would start his day at around 4am, plan things for the day and visit habitations in these dense jungles. He ensured that 100% of the taxpayer money meant for the underprivileged reached them. For example, the forest department would earlier issue payments in cash to local labourers and villagers for a variety of forestry work like plantation, weeding, construction, collection of minor forest produce, etc. This process was rife with corruption. As DFO, he made online payments mandatory so that all the money owed to them would flow directly into their bank accounts. Earlier, instead of paying the entire sum, these contractors would take a commission. For every work involving the forest department, he would share receipts so villagers would know how their money was being spent,” says Upadhyay.

Besides his integrity and honesty while dealing with people, what local activists like Upadhyay argue is how approachable the former Keshkal DFO was to the people.

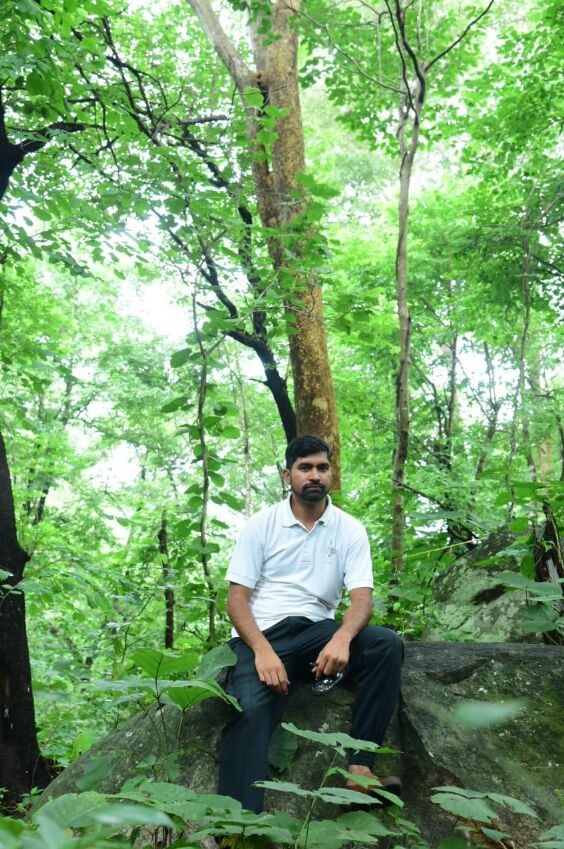

“In these parts, a forest officer is considered a big deal and often seen as unapproachable to the common people. But DFO Dhammshil would walk and cycle into the jungle, meet the people there, explain all government schemes to them and constantly emphasise that this jungle belongs to them, and not the government. In instilling this valuable sense of ownership into those from the local Gond or Pardhi tribal community, he has pushed them into the frontline of conservation work,” he adds.

Unfortunately, protestors from the Adivasi community couldn’t stop the eventual transfer of their favourite officer, who, in the span of barely six months, transformed their lives. Today, Dhammshil is the DFO in Durg district. However, locals are now demanding that the new DFO posted in Keshkal and the forest department follow the same system of transparency Dhammshil put in place, and continue the work he started.

From humble beginnings

Thirty-two-year old Dhammshil is an Indian Forest Service officer of the 2013 batch. The son of a small farmer from Amgaon village in Bhandara district of Maharashtra, his education was largely funded by scholarships, which culminated in a fellowship from the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR) to obtain his MSc in Forestry from the Tamil Nadu Agricultural University in Coimbatore.

After joining the Indian Forest Service in 2013, he spent two years training at the Indira Gandhi National Forest Academy (IGNFA), Dehradun, following which he joined the Chhattisgarh cadre. Back in 2017, he had a short stint as DFO of Keshkal division in Kondagaon district, which is adjacent to Bastar. As fate would have it, he was posted there again on 23 June 2020. Here are some of the initiatives he started during his second stint which lasted five-and-a-half-months.

Vermicompost manufacturing

Long before his posting there, three women self-help groups with 10-12 members each from the Gond community were running vermicompost manufacturing units next to forest nurseries where the forest department would prepare seedlings. However, what these women didn’t have was the training to brand and market these products. Also, as a result of a communication gap with the forest department, these SHGs weren’t getting paid on time.

“We had scientifically calculated how much they should invest into purchasing raw material and the price for each kilogramme of vermicompost. We came to a price of about Rs 8 per kg. With many plantations under our jurisdiction, the forest department requires a lot of vermicompost. Thus, the department buys it from them and there is ample demand for their product. I ensured they were paid on time. We had even made plans for proper unit-based packaging in 2 kg, 5 kg and 10 kg bags, which could one day be bought in Raipur and other nearby cities as well. This was in the pipeline until I was transferred out, besides plans of starting another manufacturing unit,” says Dhammshil.

Gobar Gas Plants

There are two facts that one needs to understand. One, it’s a common practice among members of the Adivasi community to collect firewood from the forest for cooking and heating purposes. Two, every year, the forest department embarks on timber felling operations in selected pockets of the forest. That timber is then sold in an auction to the highest bidder, which includes private contractors in the construction business.

As standard practice, 20% of the revenue generated from selling this wood is given to the joint forest management committee (JFMC), consisting of members from the local community, who protect and manage nearby forests. Some JFMCs earn anywhere between Rs 10 to Rs 40 lakhs annually from the sale of this timber, depending on how many trees were felled in a given area. But this corpus fund remains untouched or poorly utilised.

“After a series of discussions with members from different JFMCs, we arrived at a decision by consensus that we should decrease the pressure on our forests, but not at the expense of the local community. By installing gobar gas plants, they can, in one fell swoop, save money (instead of buying expensive LPG cylinders), time and their forests (instead of collecting firewood) as well. The JFMCs then sent their respective proposals for the construction of gobar gas plants. We distributed these biogas plants bought with the corpus of money available to each JFMC and piloted this in five villages first,” recalls Dhammshil.

Operations are about to commence in these five villages, while he sanctioned the construction of 250+ gobar gas plants. CREDA (Chhattisgarh State Renewable Energy Development Agency) will construct these plants. Some of the money has also been spent on setting up digital learning centres in village schools, giving them computers, projectors and digital blackboards. These digital education initiatives were sanctioned in five government schools.

Once this pilot takes off, other villages will definitely join in, he claims.

Planting of fruit bearing trees

The decision to plant fruit bearing trees like cashew, coconut and custard apple across different villages is to ensure the villagers keep on earning money even after the traditional paddy farming season is over. Keshkal division, which comes under Kondagaon district adjacent to Baster, offers suitable climatic and soil conditions for these fruit bearing trees.

“Before distributing seedlings to these communities, we divided Keshkal into a number of clusters for each fruit-bearing species depending on the climate and soil suitability. We proposed this idea of growing fruit-bearing trees to the JFMCs so that they may reap the benefits of earning additional income three to four years down the line. In the 18 villages of the Mari region on the Bastar plateau, we distributed 10,000 seedlings of cashew in the recent monsoon season. These seedlings were given and distributed free of cost by the forest department. The JFMCs of that area were given the responsibility of protecting these seedlings. This is the first time the forest department has taken such an initiative. I also sanctioned the distribution of 15,000 coconut seedlings to Sidavan and another village. Planting of these seedlings will happen in the next month or so. I got transferred out before seeing it through,” he says.

Community-based eco-tourism project

There are three objectives of any community-based eco-tourism project — educate tourists about their natural surroundings, learn about local communities living in and around these forests and sustain their livelihoods, which in the process protects the forest.

In the Mari region, where he had distributed the cashew seedlings, Dhammshil had found a couple of cottages for tourists built by the department that were lying abandoned. Upon seeing the stunning natural beauty of the region, marked by dense forests and rolling hills, he felt the site would be ideal for an eco-tourism centre.

Barely a few weeks later, on 26 September, the forest department opened the Tatamari Eco-Tourism Centre, which lies at an altitude of 2,150 feet above mean sea level, to tourists with the necessary precautions put in place for COVID-19. Located just 2 km from Keshkal, Dhammshil considers this as the ‘flagship project’ of his short tenure there.

Spread over 150 acres, this region has a variety of flora and fauna, and according to Dhammshil, this is the first eco-tourism initiative in Keshkal.

“In this project, I sought to involve members of the local Pardhi tribe, a community with a long legacy of hunting. There were 20 families of the Pardhi community living in the vicinity and I sought to convince them to give up hunting and engage themselves in the ecotourism project. Embedding their local practices, these youngsters have found work as guides for trekkers who can see 16-17 waterfalls in a 20 km trek into the forests, instructors on how to use bow and arrows they earlier used to kill wild animals or birds, and performers of local dances and other rituals. Besides, we set up eco-cottages made of only mud, wood and stone, night camping facilities, an activity corner for young children, and a cycling trail through the forest that can take you Manjhingarh,” he says.

“With this, he has helped in saving animals, while also giving employment, respect and dignity to members of this persecuted tribe,” says Upadhyay.

“We also take tourists through these parts to understand tribal food habits, delicacies, local dances and other cultural events that tribal communities here undertake. Soon, tour operators began approaching us, asking how they could collaborate with the department. All the income generated from these activities goes to the local tribal communities. Funding for the centre came from the district mineral fund, local communities and the forest department. Tribal youths were given training in hospitality, housekeeping, guide work and scientific knowledge of the local flora and fauna for the Tatamari centre. Dhammshil sir was about to do the same for three other potential centres as well, before his transfer order came,” says another local forest officer, who wishes to remain anonymous.

Other Initiatives

During his tenure, Dhammshil issued 25 Community Forest Resource Right (CFRR) certificates to gram sabhas across the Keshkal division. The possession of a CFRR certificate helps contain outside encroachment on forest land and gives local communities the right to manage and protect the forest in a meaningful way.

Another initiative is the recruitment of young children, who would often kill birds with catapults during their free time, as ‘Chidiya Mithans’ (Friends of Birds).

“In every village, we recruited the children responsible for killing these birds as their protectors instead. Two children were recruited from each village. With assistance from expert ornithologists, we trained these children, who from Class 7 and 8, on how to spot them as well as on the importance of a particular species to the local biodiversity. Under my tenure, we recruited about 60 such Chidiya Mithans to the cause,” says Dhammshil.

Finally, during his tenure, he established a central control room for grievance redressal that residents from all villages can access.

“Anybody could call the DFO or Range officer or SDOs to file any grievance. I also organised a workshop for all the JFMCs, for which about 700 people turned up. During this workshop, I explained to them the role of these committees, how they should draft proposals to government officials, the rights and benefits they are entitled to, how they can utilise the money at their disposal to ensure greater livelihood security and how they can better benefit from the forest, among other things,” he says.

“In his letter seeking Dhammshil’s transfer, the MLA claimed that some of the other officers working there were not happy with his style of working. These must be officers who never wanted to work in the first place or earn money in corrupt ways. After his transfer, we have lost hope because for politicians we are nothing but votes. When it comes to fulfilling our demands, they go missing. We cannot even explain in words what this one officer has done for us and our forests,” says the president of a JFMC, who wishes to remain anonymous.

(With inputs from Nisha Dagar)

(Edited by Divya Sethu)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167