From Servants to VP Nominee: How Indian Immigrants Climbed The American Ladder

We know about the countless contributions of Indian Americans. But do we know about their struggle to become equal citizens in America?

Going by historical records, the first Indian emigrant arrived in the US in 1790. Early on a number of Indians found work mostly as house help in the homes of sea captains working for the East India Company.

“Only a trickle of other Indian merchants, seamen, travelers, and missionaries followed, amounting to a total population of less than a 1,000 by 1900,” writes historian John P. Williams, in his book, Journey to America: South Asian Diaspora Migration to the United States (1965–2015).

Today, Kamala Harris, a second generation Indian American, is the vice presidential nominee of the Democratic Party for the upcoming US general elections.

Like many minority communities who first came into the United States, Indian immigrants too had to deal with widespread xenophobia, structural racism, violence and an unempathetic judicial and political system. For decades, America was the land of the free and home of the brave, but only for its white constituents.

But many Indians, who had made their way to this land of opportunity, were never going to take this injustice lying down. They fought for their right to become US citizens, make this country their home and even established alliances with other minorities like Mexican- and African-Americans.

Early Struggles

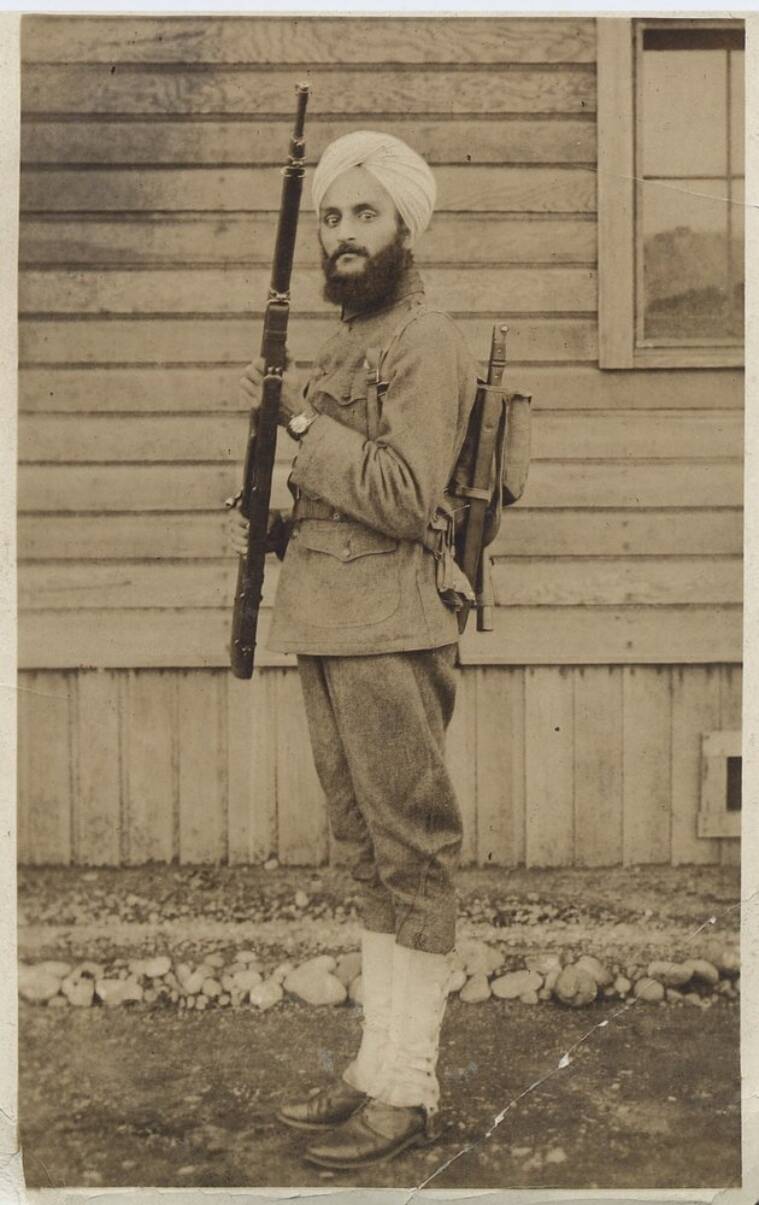

“By 1910, the number of Indian immigrants slowly rose to 3,000, having settled on the Pacific Coast as agricultural workers. Many were Sikhs from Punjab seeking better fortunes in the West. Additional immigrants would come and work on the Western Pacific railroad and take employment in the lumber mills of Washington State…In the early twentieth century, hundreds of South Asians, mostly Sikhs but also many Muslims, came to North America from Punjab—the vast majority of them former soldiers who had served in the British colonial army in East Asia. While many Indian laborers came as ‘sojourners’ rather than as settlers; they lived frugally, and their sole objective being to return to Indian with their savings. Instead of returning home to a farming economy under severe stress due to British colonial practices, they sought their fortunes in various settlements on the West Coast, between Vancouver and San Francisco,” writes Williams.

On the East Coast, however, a different set of immigrants from the Indian subcontinent were making their presence felt. These were Muslim traders from Bengal who set up shop in the 1880s as sellers of ‘exotic products’ like rugs, performs, and embroidered silk, amongst others.

In his book Bengali Harlem and the lost histories of South Asian America, writer Vivek Bald presents a remarkable finding. “As they accessed white consumers with fantasies from India, their pathway into and across the United States was a pathway through working class Black neighbourhoods,” he writes.

One neighbourhood where these immigrants cohabited with African-Americans was Treme in New Orleans, popular for its music and culture.

“Here some of the Bengalis married and started families with African-American women, who were part of recent Black migration into the city, or with Creole of Colour women who had deep generational roots in Treme,” writes Bald.

The next wave of immigrants from India followed were those who had escaped from British steamships during World War I. Indian maritime workers who manned the kitchens and engine rooms of these ships escaped to cities like New York, Baltimore and Philadelphia in search of better pay and working conditions. Most of these workers were from present-day Bangladesh, Punjab, Kashmir and NWFP (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). In cities like New York, they found work in the low-paying service economy as elevator operators, cooks and dishwashers.

When these immigrants found their way into America, they were subjected to racism. Similar to current discourse about immigrants taking away jobs from ‘Americans’ (a term that means different things for people on different ends of the political spectrum), then too, there was opposition to Indian immigrants as they accepted lower wages for menial jobs.

When hundreds of Punjabi workers arrived in California and the Pacific Northwest, they were met by white civil society groups and labour unions demanding they be sent back.

In December 1907, the Asiatic Exclusion League, an anti-immigrant organisation, came into existence in San Francisco. It was earlier called the Japanese and Korean Exclusion League, but with the growing inflow of Chinese and other South Asian immigrants, they changed their name. This organisation would go on to lobby members of the United States Congress to introduce harsh anti-immigration law and use violence as a means to ensure there was no rise in the Asian population across the West Coast.

Apart from this, immigrants had to face racist attacks too. One such violent attack was in the town of Bellingham in Washington, where white mill workers rounded up Indians from their homes and jobs in September 1907.

A decade later, Congress passed the Immigration Act of 1917, which was popularly known as the Asiatic Barred Zone Act. This piece of legislation prevented all Asians from entering the US unless they found jobs with high educational requirements.

According to Williams, as a result of this Act “1,700 Indians were deported while 1,400 left voluntarily”. The next body blow for Indian immigrants came in 1923, when the US Supreme Court passed its ruling in the United States vs Bhagat Singh Thind case.

Thind had fought in the US military during World War 1, and sought American citizenship. However, the court denied his request. Prior to his application, “very few foreign-born Indian immigrants had become US citizens by exploiting ambiguities in the pseudoscientific race theories of the time, by claiming ‘north Indian Aryan’ ethnicity and hence membership among Caucasians and ‘free whites’,” notes Williams. The court closed this loophole stating “he would not be considered ‘white’ in the eyes of the ‘common man’ despite scientific race categories, and was therefore also ineligible for citizenship,” states Immigration History.

Following the judgement, the government stripped Indian immigrants of their citizenship even though they had already been naturalised and also blocked any pathway towards naturalisation.

“Some immigrants returned to India, unable to bear the racism and limited opportunities. As a result, the Indian population in the United States dwindled to 2,405 by 1940,” write authors Sanjoy Chakravorty, Devesh Kapur and Nirvikar Singh, in their book The Other One Percent: Indians in America. The few who came were primarily students.

Fighting Back

Following the Supreme Court’s Thind ruling, six Asian Indian civil rights organisations were created to fight for citizenship. These organisations were the Hindu Citizenship Committee, the Indian Association for American Citizenship, the Indian National Congress of America, the Indian Welfare League, the National Committee for India’s Freedom and most importantly the India League for America.

It was the India League for America, once a non-profit comprising private individuals discussing Indian literature and philosophy, which morphed into an effective political lobbying entity under the aegis of Sirdar Jagjit Singh, when he took over as its president in 1941. Singh had moved to New York in 1926 from Rawalpindi, and “established a business supplying luxury Eastern imports to the city’s elites”.

Despite great odds, he ensured the India League for America became the voice of the 4,000-member strong Indian community in America, and heavily lobbied Congress.

Fortunately, for Singh, a few mitigating factors began working in his favour.

“World War Two and the U.S.’s alliance with India brought new changes and beginnings. South Asians in the U.S. lobbied politicians to revise the immigration laws and to build support for Indian independence,” notes Erika Lee, writing for South Asian American Digital Archive. In his proposals, Singh makes a strong case for why Indian should not be excluded from American society.

“The people of India have no desire to ask for any special privileges or treatment. They do not seek unrestricted immigration into the United States, but they do wish and ask that the stigma of inferiority be removed,” he wrote.

“Democratic and freedom loving Americans are certainly not shedding their blood for the continuance of racial discrimination, racial intolerance, racial superiority, which are Hitlerian theories and must result in wars,” he added.

Another central figure in this battle for Indian immigrants was Mubarak Ali Khan, who had settled in Arizona’s Salt River Valley back in the 1910s. Along with some other farmers from the Indian subcontinent, he had converted fallow lands stretching hundreds of acres into thriving fields growing rice. His rationale for greater inclusion of Indians in American society was a little different.

“It sought naturalisation rights for the roughly three thousand Indians who were estimated to have settled in the United States prior to the Supreme Court decision of 1923….most of these immigrants were farm and factory labourers – exactly the population of ‘undesirable aliens’ that the 1917 immigration Act had sought to keep out of the country,” writes Bald.

In March 1945, both men testified before the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization of the US Congress, pushing their proposal for citizenship. They spoke extensively about the contribution of Indian immigrants in academia, science, medicine, agriculture, infrastructure building and participation in the War effort. Another Bengali from New York City, Ibrahim Choudhury, who was representing South Asian workers along the East Coast, encapsulated that argument in a letter he wrote to the House Committee.

“I talk for those of us who, by our work and by our sweat and by our blood, have helped build fighting industrial America today. I talk for those of our men who, in factory and field, in all sections of American industry, work side by side with their fellow American workers to strengthen the industrial framework of this country…We have married here; our children have been born here…I speak for such as myself, for those of my brothers who work in the factories of the East and in Detroit…I speak for the workers and the farmers of our community whose lives have been bound to this country’s destiny for 23 years or longer,” states his letter.

Finally, after much lobbying, President Harry Truman signed the Luce-Celler Act of 1946, which allowed South Asians to apply for admission and become naturalised US citizens. “All immigration, however, was subject to the discriminatory national origins quotas that were still in place, and India’s quota allowed only 100 people in per year,” writes Erika Lee.

From hereon, the movement for greater inclusion of Indian Americans, rode the wave of the Civil Rights Movement. It was the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 which really opened the floodgates for the arrival of Indian immigrants into America.

As Lee writes, “Inspired by the Civil Rights revolution in American society, the 1965 Immigration Act explicitly abolished the discriminatory national origins quotas that had regulated entrance into the country since the 1920s. It explicitly prohibited discrimination on the basis of race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence in the U.S. government’s decisions to issue immigrant visas. Instead, the law established a new preference system based on professional status and family reunification.”

Indian-American comedian Hasan Minhaj even makes a reference to this point in one of his sketches earlier this year while speaking on the murder of George Floyd. “We’re in this country because of protest — because of the Civil Rights Movement. The only reason so many of us are here is because of The Immigration Act of 1965. That law rode the wave of the Civil Rights Act of ‘64. Think of the chess moves. Martin [Luther King] gets Lyndon B Johnson to sign that sheet of paper, and little do we know, MLK CC’d us on that email of progress.”

By 1980, the Indian immigration population in the US was 206,000. As of 2018, the number of Indian immigrants in the United States is 2.65 million.

By any stretch of the imagination, this is a remarkable story, which many of us back in India don’t really know about. From working in menial jobs, either in railroads or hard labour in lumber mills, to now being represented in almost every facet of American life, Indian Americans have come a long way.

Feature Image: In June 1946, president Harry Truman signed the Luce-Celler Act that paved out an immigrant quota. (Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons)

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.