From Goalpara to Star Trek & Beyond: Meet Adil Hussain, The Complete Actor

“When I see the history of Indian film industry, apart from Danny Denzongpa, who was mostly given negative roles because he looked different, when have you seen faces from our part of the world?”

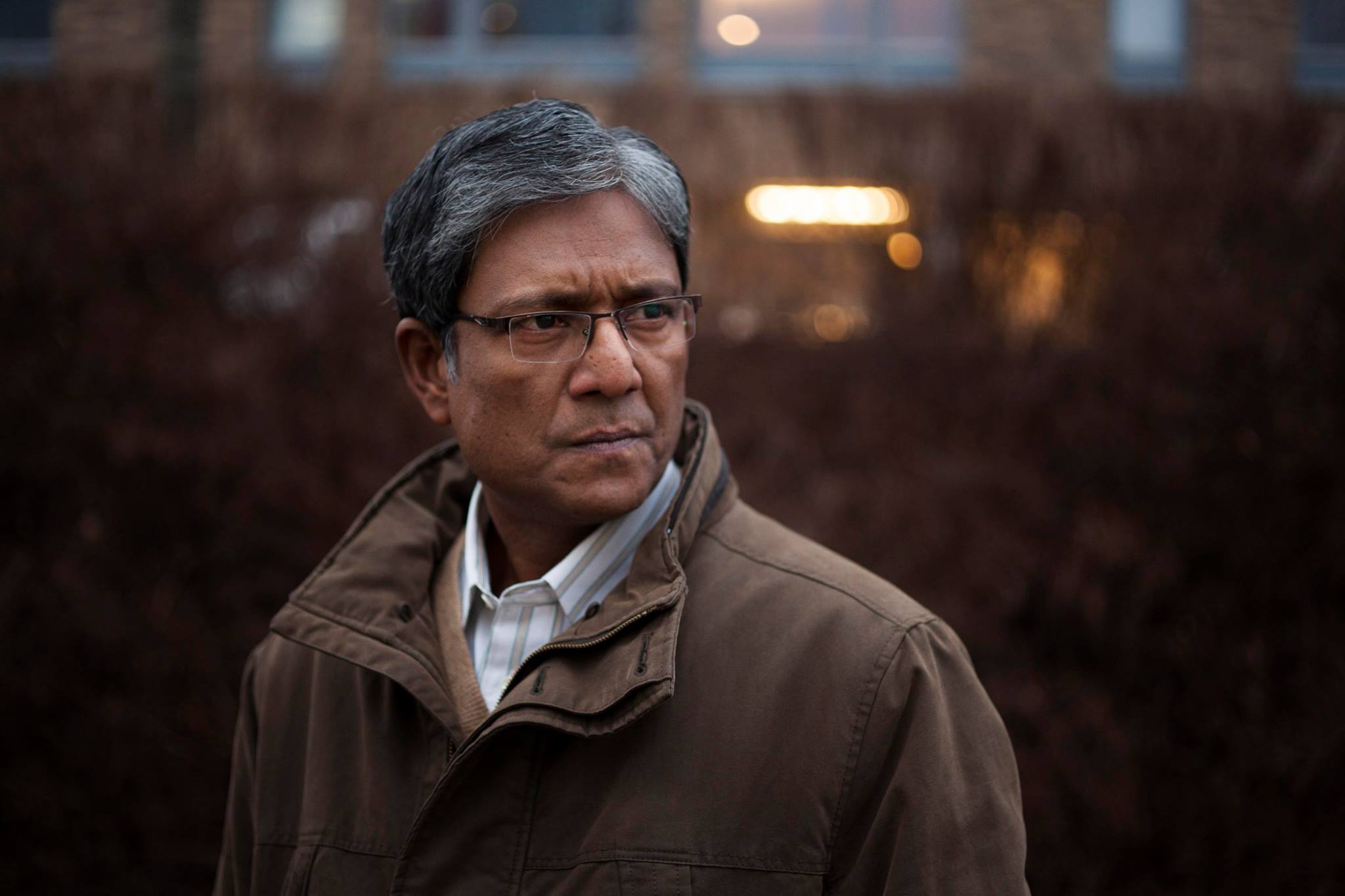

When you talk about Adil Hussain, the first thing that comes to mind is the sheer range of characters he can embody. He can seamlessly pull off playing characters ranging from a suave Commissioner of Police in the Netflix web series Delhi Crime to a rickshaw puller scrounging for a living in Ranchi in the Prakash Jha-directed film Pareeksha.

Speaking to The Better India over a video call from Scotland, where he is shooting a film, Adil describes how he captured the accent, demeanour and behaviour of a good-hearted rickshaw puller from Ranchi called Buchi Paswan, who does whatever it takes to ensure his son, Bulbul, has access to quality private school education.

“With great training, you understand physical and inner flexibility or adaptability to different body languages. That’s the fundamental training of an actor. When I say inner flexibility I mean the flexibility of your ideas, beliefs, emotions, worldview and morals. As an actor, you have to let go of them so that you can move from one role to the other in the spectrum of characters between Hitler and Jesus Christ. All of us fall within that spectrum,” says Adil.

However, he also grew up watching rickshaw pullers as a young child growing up in the small town of Goalpara, Assam, as the youngest of seven children in his household. In Goalpara, the prime mode of transportation was cycle rickshaws. His next door neighbour had rented out their hut to a rickshaw puller from Bihar.

“I remember his name, smell and demeanour. His name was Noor Mohammed Bhai, and he used to give me free rides. I would even go with him to the mechanic shop to fix his rickshaw. As far as the accent goes, I grew up listening to so many people from Bihar, who would come for work in Assam and still do till this day. They would do the odd jobs that Assamese people wouldn’t, which is actually hard work,” he recalls.

What Adil could also relate to was the economic hardships that his character in Pareeksha, Buchi Paswan, undergoes. “We grew up in a very humble household. We had land but very little cash. My father was a school teacher, who gave up the job, and became a Muslim marriage registrar with no fixed salary at all. There were days when we ate dry rotis and tea without milk since we couldn’t afford it,” recalls Adil.

Also, his father could only afford to pay for the college education of two of his eldest sons who studied law in Guwahati University. In 1982, when it was Adil’s turn to go to college, his father had retired and could only give him Rs 250 to study philosophy at B Borooah College, Guwahati.

“This amount was nothing even back then. Thus, playing the role of a poor rickshaw puller wasn’t very far from either my reality or the people I observed around me. Also, I have always been very curious and interested about accents. Since Class 7 onwards, I was a mimic actor who performed on stage. So, I had a good ear for accents as well,” he says.

Early Days on Stage

During his time in college, Adil started acting in college plays and performing as a satirist in street plays. He also mimicked popular Hindi film actors in between the performances of a local street theatre group engaged in political satire called the Bhaya Mama Group.

“There were four of us in the group and it was fearless political satire. Some people even say that we were covertly responsible for the fall of two State governments. We criticised the hell out of these governments, but with a lot of love, respect and humour. We knew these politicians very well, often referring to them as ‘Dada’ (Elder Brother). It was like criticising my elder brother for things he was doing wrong. We had the courage to do it,” says Adil.

In their pieces of political satire, they had a lot of characters to create the drama. Adil was responsible for the mimicry part and also two characters that they made up. In their performances, the Bhaya Mama Group would speak about the prevailing socio-political conditions and comment on them. The structure of the narrative, however, was based on a traditional folk form called Oja-Pali, which satirists would perform in front of kings and queens in ancient times. These performers would comment on the political situation through a melodious presentation, and would even criticise kings and queens.

So, the narrative of the Bhaya Mama Group’s performances was based on the Oja-Pali folk form, but instead of singing, they spoke. The narrative revolved around two characters — Gogoi and Bhaya Mama. While Bhaya Mama asked questions, Gogoi answered, and then they would call different characters on stage and interview them.

“It was so much fun. I did this for five years until I left for the National School of Drama in May 1990. During this time, I did a lot of mimicry and invented many new characters. Simultaneously, I did films, theatre, television, radio plays, street plays, video films and tele films. You name any form or discipline of the performing arts, and I have done it. However, when I began looking at myself, I realised acting is a serious craft that I needed to learn. Fortunately, when I landed at NSD, I already knew my weaknesses as an actor. So, my questions were very different from other actors who didn’t do as much,” he says.

In Delhi, Adil began his stage career, while also continuing to receive training from some of the most distinguished figures in Indian theatre including Khalid Tyabji and Dilip Shankar.

What did he learn from his gurus?

“It would take months for me to articulate what I learnt from them, but I will give you a little insight. The actor’s instrument is the body and whatever is within it. It’s imperative to understand the instrument you’re playing. While a guitarist has her guitar, she has to tune it and keep it clean for future performances. For the actor, the player and instrument are rolled into one. I have to understand how this instrument works. How do emotions work? How do nerves work, how each and every muscle has its own memory, and how breath is related to emotions. You breathe in a certain way because you feel in a certain way. When you’re angry, your breath is the first thing that gets affected. If you see something outside which is undesirable, the breath is the first thing which gets affected. That breath leads you to feel in a certain way. It’s about acquiring an intimate understanding of these dynamics,” he says.

After NSD, he studied at the Drama Studio London on a Charles Wallace India Trust Scholarship for a year before returning to India in 1994.

Besides receiving much acclaim for his theatrical performances, which included the Edinburgh Fringe First award in Scotland, he also trained actors at the Society for Artists and Performers in Hampi (2004 to 2007) and was also visiting faculty at the Royal Conservatory of Performing Arts in The Hague, Netherlands, and NSD.

However, during this time, he also began acting in more mainstream film productions like the period drama Iti Srikanta opposite Soha Ali Khan, which was in Bengali.

He also did a series of Assamese films and small roles in the Hindi Film Industry like Vishal Bharadwaj’s Kaminey (2009). However, it was his role in the 2010 film Ishqiya, where he acted alongside high-calibre Hindi actors like Naseeruddin Shah, Arshad Warsi and Vidya Balan, when he got the attention of more mainstream filmmakers.

Since then, he hasn’t looked back performing in landmark films like English Vinglish opposite Sridevi (2012), Lootera (2013), Umrika (2015), Delhi Crime (2018) and even mainstream films like Agent Vinod, Kabir Singh and Force 2.

Of course, there are his mainstream films in other regional languages as well like Assamese, Bengali, Tamil, Marathi and Malayalam. But it’s his international projects that garnered him greater recognition like in Italian director Italo Spinelli’s Gangor, Mira Nair’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist, Ang Lee’s Life of Pi and the Norwegian film What Will People Say, which was Norway’s entry to the Oscars in 2018.

But what was that transition like from serious theatre to mainstream films? What is the difference between acting on stage and in front of a film camera?

Listen to how he articulates that difference in this clip.

“Adil is someone who has spent a long time developing his craft, and as a consequence, knows and understands it very well. It’s a massive deal for artists from the Northeast to see a person from a small town like Goalpara, reach the heights both in national and international cinema. Another thing which is very impressive is how he keeps himself fit. It takes a lot of effort to stay fit and remain good looking on screen like he does. In my opinion, he is the complete actor,” says fellow actor Kenny Basumatary, who worked with him in the 2014 Assamese film Raag directed by Rajni Basumatary.

Acting in Multiple Languages

Adil has starred in films spread across a multitude of languages, although he claims to be fluent in only four languages.

Thankfully, he says, the scripts come beforehand, and so one understands each and every word spoken. As an actor, one learns the nuances of the dialect, accents and the rest.

“When it comes to French films, for example, they pay you well, give you time to learn the language and pay for those lessons as well. So, you have the time, you sit, learn, prepare, go to the set and enjoy the process. Language and accents are among the most mysterious phenomena in human civilisation. When you speak a language, you understand a community’s psychological state of being. When you speak a language, the accent and sound, it makes you feel a certain way. So, my training as an actor is also to discover the meaning of the word through its sound. When you utter the word with the right phonetics, you also feel the meaning rather than merely understand it intellectually. It bypasses your intelligence and becomes an experiential understanding rather than an intellectual understanding and I am way more fond of the former,” says Adil.

Cultural Differences

When asked about the difference between acting for domestic filmmakers versus the likes of Ang Lee and Mira Nair, Adil does not delve into direct comparisons, but answers the question in terms of how one sees the world.

In this regards, he talks about his father, Zaharul Haque Md Muhiuddin, who despite living in a small town all his life was among the most ‘liberal persons’ he had ever met. Adil speaks about one particularly valuable lesson he learnt from his father, an atheist, when he was in Class 5.

“I came home one day telling father that my Arabic teacher wanted me to shave the hair inside my nose, armpits and pubic hair, whereas science books spoke of how nose hair blocks dust and saves us from viruses. When I asked him what I should do, he told me not to trust either science or religion, but find out for myself. His philosophy was experiment, find out whether it’s true or not and then accept it, but otherwise doubt everything. Similarly, he told me later that I could marry whoever I liked from whatever community and how she’ll be accepted by the family regardless,” he recalls.

In terms of cinema, Adil believes that when a creator’s worldview is broader, more liberal and can approach the truth from multiple dimensions and perspectives, then one makes a better film which will have a global impact. Attitudes like his father’s in the domestic film industry, he believes, are the exception, rather than the norm.

“We have a bunch of unbelievably talented people working on our films, but in terms of orientation, the culture of filmmaking, those who fund the films, and their dominance and dictations that directors and writers have to take into account even while conceiving a film, is a big problem. If a screenwriter writes a scene thinking who’ll produce it, they’ll start climbing down the ladders of their creativity to present a ‘more acceptable’ version. So, they stop thinking, imagining and doing things which will be way more meaningful, multi-layered or multi-dimensional. Thus, these films end up adopting a binary narrative rather than a multi-layered one. This difference exists not because of the lack of creativity amongst our filmmakers, but the traditional production culture that we have,” he says.

Even when discussing some of the finest actors he has worked with which include Naseeruddin Shah, Irrfan Khan, Tabu, Sridevi and Vidya Balan, he harks back to the stark cultural differences that lies when working with actors on the set of a domestic project vis-a-vis an international one.

“When you talk about international actors, there is a particular culture that they bring with them while creating in a particular environment. There is this extreme priority given to human to human connection between the actors. Take the example of Gerard Depardieu, the Amitabh Bachhan of France, who I worked with in Life of Pi. He never cared about who I am, or where I have come from. All he cared about was that I was a human being and an actor. He treated me as his equal. In Star Trek: Discovery, a CBS All Access web series, the lead actor Sonequa Martin-Green treated me like her equal. The first thing she did when we met on set was give me a tight hug. She said ‘I’m so looking forward to working with you, Adil’. That broke all boundaries or hang ups we generally face in India. We face these hang ups in India because there exists a feudal system not just in the film industry but in every household. That feudal attitude is ingrained in us, which reflects in our films and every sphere of life,” he says.

Representing Cinema From The Northeast

Despite his wide appeal, Adil never misses a chance to appear in films based in the Northeast. Following him on social media, it’s hard not to see how passionately he waves the flag for cinema in the Northeast.

From Bhaskar Hazarika’s independent Assamese horror film Kothanodi (2016) to Wanphrang Diengdoh’s debut Khasi film set in Shillong called Lorni – The Flaneur (2019), he has delivered stellar performances.

In Lorni – The Flaneur, Adil plays an unemployed detective in Shillong who gets involved in a case about missing family ornaments. While the film is largely in Khasi, it’s interspersed with English and other languages spoken in this multi-ethnic city. He takes a chance on these essentially low-budget films because of the stories they’re telling written by filmmakers who possess a kind of vision not always seen in mainstream cinema. Moreover, he believes cinema from the Northeast can seriously bridge this cultural gap.

“We know what Bombay (Mumbai) looked like since our childhood through films starring Amitabh Bachhan, Dilip Kumar and Randhir Kapoor. We know about the Sun-n-Sand hotel in Juhu sitting in Goalpara. We know Bombay culture and the way they talk. The more you see a place, its people and culture on screen, the more you familiarise and accept them. When I see the history of Indian film industry, apart from Danny Denzongpa, who was mostly given negative roles because he looked different, when have you seen faces from our part of the world? Cinema is a very powerful medium for people to educate and familiarise them with different cultures. Across the Northeast, we have such talented people,” he says.

“He has definitely brought greater attention to cinema from the Northeast. A person like him can ideally occupy himself with big Bollywood or international projects, but he regularly comes back to do Assamese films as well. Those films automatically become bigger when he stars in them,” says Kenny Basumatary.

What can be done to strengthen cinema in the Northeast?

For Adil, the biggest hurdle remains the lack of knowledge amongst the authorities about what role art plays in human society. Art is a powerful tool and gives people an avenue to express themselves.

“When you can express yourself, you become a lighter person. You don’t hold grudges or seek revenge because you have expressed yourself and that somebody has listened to you, seen your work and recognised you. Expressing yourself through art makes you an emotionally lighter person and more accommodating. The lack of understanding of the role art plays in society amongst the people who hold the reins is criminally bad. We need institutions that can skill aspiring artists. We need a lot of work in educating our filmmakers on how to write a script. I know this because I keep reading scripts from different parts of the world. We need proper film institutes where people from different parts of the world can teach. I don’t see a difference in talent, but just in terms of orientation and guidance. With that sorted, you’ll see many more marvellous films from the Northeast,” he says.

“The way he conducts himself in public is one of the things I have admired. He is a very generous person as well with his time and knowledge. But what I admire the most is the way he interacts and carries himself with such dignity, patience and generosity,” says Kenny.

Education for All

His point about the need for better education harks back to that moment in Pareeksha, where one character, who is the only college graduate in the basti, talks about how he could never make much of himself without the necessary guidance. And for those who haven’t watched the film, Adil wants them to take home the gross inequities of our education system.

“Back in our days, there were only government schools. These schools attracted good and passionate teachers. Not wanting to generalize here, but quite often I have seen that those who become teachers at government schools today haven’t found anything better to do. There are no other jobs available for them. They are also paid very little. On the other hand, the focus on private schools is growing all the time and the elite class don’t worry about the rest because their children are going to the best schools. I believe that school and college education should be made tuition-free for everyone. I am sitting here today in front of you because I got a free education. The current inequities of our education system is depriving our nation of this amazing pool of talent,” he says.

And that answer in some ways captures the beauty of talking to Adil Hussain, who always connects the dots between films and real life.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.