Meet ‘Mr Ranthambhore,’ The Forest Officer Who Showed India How to Protect Tigers

One lesson that forest officers today can learn from Fateh Singh Rathore’s life is that their loyalties should only be with the forests – and not politicians or superior officers.

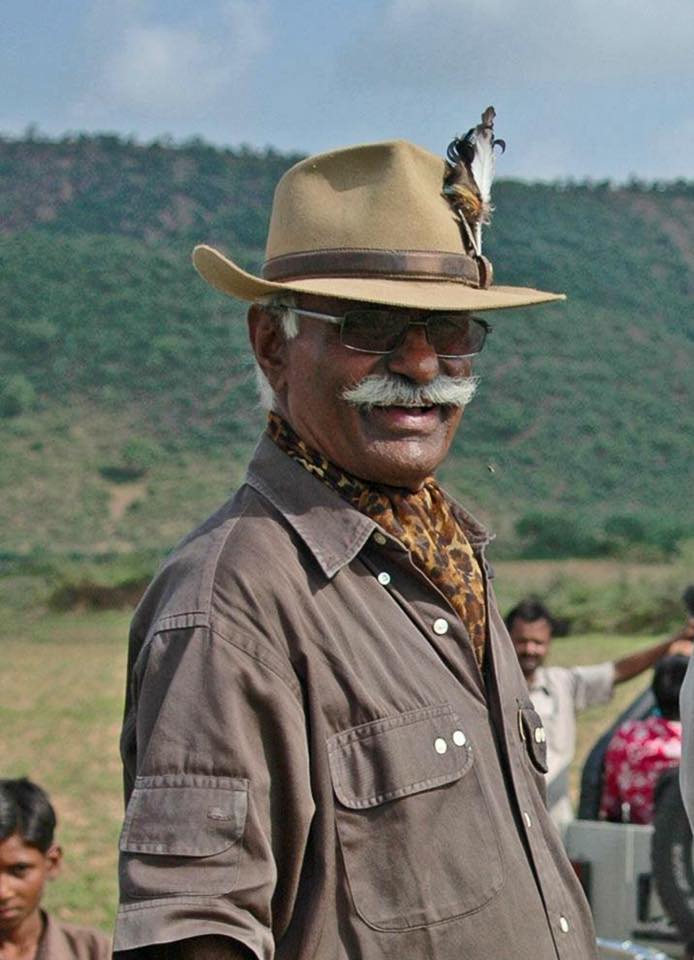

When the history of tiger conservation in India is written, there is one figure whose indelible contributions will never be forgotten. Known for his trademark long handlebar moustache, olive-coloured safari hat and dashing dark glasses, the late Fateh Singh Rathore remains the principal architect behind the success story that is the Ranthambhore National Park.

In February 2011, when the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) presented its lifetime achievement award to Fateh for his stellar conservation work, Divyabhanusinh Chavda, the then president of its India chapter, stated that “Ranthambhore became the place which brought the tiger to the consciousness of people the world over” because of him.

As a ranger, warden and field director at one of India’s best-known tiger preserves, Fateh’s work in Ranthambhore, which emphasised on the natural regeneration of the habitat, constant engagement with local communities living in its vicinity that went way beyond consultations and an abiding love for the creatures who inhabited this dry deciduous forest — became the blueprint for what a successful tiger conservation strategy looks like.

Speaking to The Better India, Bittu Sahgal, the founding editor of Sanctuary Asia, who knew Fateh closely for over four decades, talks about a time in the early 1970s when there were barely any tiger sightings.

“When we saw a piece of tiger droppings (faeces) once in 10 days or even fresh pugmarks, we would come back to Fateh’s Jogi Mahal home, sit around a campfire under the great banyan tree and celebrate the fact that we had hard proof that tigers were actually walking Ranthambhore’s coming-back-to-life trails,” says Bittu.

From a time when the national park saw just transient tigers passing through, today it boasts of a population of over 70. Even after his near 10-year stint as Field Director (1978-1987) and post retirement from the Indian Forest Service, he continued to tirelessly work towards ensuring that both the national park and communities living in its vicinity thrived.

Having said that, credit for the success of Ranthambhore and its popularity must also go to his protege, fellow conservationist and close friend Valmik Thapar.

“Valmik had a major role to play in the resurrection of Ranthambhore. While Fateh did work on the ground, Valmik served as his sounding board and brought national and global attention to the tigers of Ranthambhore through books, films and media buzz, including international media. Valmik also managed to draw considerable political support for Ranthambhore. Sanctuary Asia magazine, which I have now edited for four decades, was born under the famous banyan tree there. Sanctuary then conceived and produced 30 weekly documentaries and docu-dramas including 2 on Ranthambhore. There was no clutter of channels then and through Doordarshan we managed to get 30 million viewers over a period that stretched for almost a year,” adds Bittu.

Early Days

Born on 10 August 1938 in the Chordiyan village of Jodhpur district, Rajasthan, Fateh was the eldest of 11 children, and known for his “mischievous, cheerful and exuberant nature” according to biographer Soonoo Taraporewala. His father, Sagat Singh, was a police officer who also oversaw the family property near Jodhpur.

After graduating from Rajputana University in 1960, he worked odd jobs before his uncle, who had become the Deputy Minister of Forests in Rajasthan, offered him a job as a forest ranger in what was then the shooting reserve of Sariska. It was at Sariska where he found his calling in life encountering not just his first tiger, but also learning the art of tracking animals from an old forest guard there who stole morsels of meat from tiger kills.

Incidentally, the first tiger Fateh ever saw was the one shot by the Duke of Edinburgh in January 1961, for whom (alongside Queen Elizabeth II) he had organised a tiger hunt in an area which would later become the Ranthambore National Park.

After his posting as game warden at Sariska, he worked at the Mount Abu Game Reserve from 1963 to 1970. The next major landmark came when he was sent as part of the first batch of forest officers to be trained at the Forest Research Institute, Dehradun, in 1969.

Six of the nine-month course at FRI was dedicated to field work, and under the able guidance of Saroj Raj Choudhury, also a legendary forest officer, Fateh learned the finer nuances of wildlife conservation. Choudhury took the young Fateh alongside other recruits all over India from the Rajaji National Park in Uttarakhand to the Gir Forest of Gujarat closely observing all sorts of wildlife.

“Fateh knew he was a favourite with Choudhury. He soon got into the habit of sleeping with his shoes on, because he could never tell when Choudhury would turn up to take him trekking a moment’s notice, having recognized the keen interest and potential of the young man,” writes Soonoo in her book Tiger Warrior: Fateh Singh Rathore.

Ranthambore Beckons

After the course, Fateh was transferred to Ranthambhore in November 1971 as a Ranger, and then upgraded to the post of Warden. However, what followed was a time of great change in the wildlife conservation landscape of India.

While the population of tigers was estimated at around 40,000 at the beginning of the 20th century, excessive hunting and poaching had resulted in a significant drop, and in the early 70s opinion was unanimous that the tiger population had drastically gone down.

Consequently, the decade saw the enactment of the Wildlife Protection Act (1972), the establishment of Project Tiger (1973), signing onto the Stockholm Declaration (1972) and Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of Wild Fauna and Flora (1973).

In April 1973, Prime Minister India Gandhi established Project Tiger starting with nine reserves to “protect and restore natural habitats of tigers and to track and protect the remaining wild tigers in India” and chose Kailash Sankhala as its first director, who, in turn, handpicked Fateh as a member of its first team.

“When Ranthambhore was chosen among the nine, most people thought nearby Sariska Tiger Reserve would be a better bet since it had more proven tigers and was relatively well-established. But Fateh and Kailash Sankhala took Ranthambhore on as a challenge, believing that two stars in Rajasthan’s firmament would be better than one. Ranthambhore became Fateh’s life. He definitely chose a tough battle. His life in Ranthambore soon became both a challenge and love affair,” recalls Bittu.

The Long Road

More than a highly qualified forest service officer, he was a local who came to know the terrain even better than the villagers who once lived inside what is now Ranthambhore’s core area.

“Fateh rarely spent much time at his office in Sawai Madhopur, preferring to be with his tigers and his team in the heart of the forest. He led his team from the front, walking trails, fighting forest fires and chasing herds of cattle out of the fragile forest. Standing with him on the upper reaches of the hills was a lesson in conservation. A map in hand, he would peer through his binoculars from vantage points and say, ‘That is where we will build an anicut to improve water availability for herbivores.’ However, carpet bombing the forest with one waterhole after another wasn’t for him. He wanted some areas to remain dry so that chinkaras (Indian gazelles) and other arid zone animals were able to thrive too. By improving the three key lakes, he managed to localise tigers and other wild animals, and this to a great extent reduced human-animal conflict. When he saw monkeys up in trees he would say ‘look at my free labour. They plant trees by scattering fruit seeds without being paid to do so’,” recalls Bittu.

Among the soundest pieces of advice Choudhury gave him was to ensure the texture of the land never changed, and that the roads should skirt water only at a few points, so that animals could have undistributed access to it.

“The roads were to be planned through all kinds of terrain, winding routes, on which the maximum speed should never exceed thirty kilometres an hour, Choudhury would tell Fateh. This sound guidance was followed meticulously, and the results manifested themselves brilliantly as the forest regenerated and animals returned to their habitat,” writes Soonoo.

What he also did was localise the tigers by organising baits.

“To localise the tigress with cubs and prevent it entering villages, he would tie a bait like the way Jim Corbett used to do to locate his man eaters. If he did not do this, the tigress and her cubs would all die from poisoning or trapping in nearby villages. Fateh was instinctive. The slightest sounds would cause him to halt in his tracks. There is not a trail his men walked that he did not know, even at night. After spending 30 minutes with a tigress and her four sub-adult cubs, we once had to walk five kilometres in the dark of night from Milak Talao to Jogi Mahal because our vehicle stalled. He knew his forest better than poachers,” says Bittu.

However, the toughest challenge standing before Fateh in 1973 was to relocate 16 villages inhabited in the core area of the Ranthambhore National Park. These communities were all inside living with their cattle and ploughing most of the land that would have normally offered grazing land for the deer — a key component of tiger food.

“This was creating additional pressure on the forest park with the people living outside suddenly seeing more mature grasslands where they could take their cattle grazing. My father zealously protected the park, but he began to realise more and more that keeping people out of the park using force was not something that was going to last,” says Dr. Goverdhan, Fateh’s son, in a 2016 documentary.

“He went about his task (of resettling villages outside Ranthambhore) using a great deal of patience and tact, finding out from the villagers what they would want as compensation. Project Tiger ensured that the villagers were compensated with better land outside the park area, with five additional bighas of land being given to every male over the age of 18. They were also provided with money to build houses and dig wells, and were in addition given a health centre and a school, facilities that they had never had in the past…Once the villages were moved out, the forest began to regenerate on its own, becoming the incomparably beautiful Ranthambhore National Park, and in 1976, Fateh finally saw his first wild tigress there, naming her Padmini after his elder daughter,” writes Soonoo.

By 1976, he had managed to relocate 12 villages. However, the process wasn’t easy on him by any stretch. In an interview with Sanctuary Asia, Fateh recalled, “The people hugged the trees and wept. I was crying with them because, inside me, I knew they were paying the price for something they may never understand.”

“In those days, the objective of Project Tiger was to separate man and animal. In fact, there were about 25,000-30,000 cattle inside Ranthambhore at one point and it took a long time to ensure that livestock was moved out or they would leave no grazing for wild herbivores. Fateh’s logic was impeccable. He said if we ensure that herbivores have abundant food, water and shelter inside the forest, farms would be relatively safe from crop or livestock losses. But that is not to say there was no conflict,” says Bittu.

These tensions almost cost him his life. Fateh was almost killed in August 1981, when a group of 50 villagers attacked him. They brutally beat him up with sticks and left him for dead. He had to spend three months in the hospital.

“In August 1981, a group of disgruntled men from Uliyana village attacked me and left me to die with multiple fractures and a head injury. The villagers were angry as they could not take their cattle for grazing or cut firewood from the protected area of the forest,” he recalled in this 2011 interview.

Despite the anguish, he was determined to not just produce results but also engage with villagers, eat at their homes and talk to them. “The forest and all its creatures were the creation of the gods, he (Fateh) argued over the village fires. Did not the goddess Durga, the slayer of demons, herself ride a tiger? No man had a right to disturb that divine creation. The forest must be left to grow back,” writes author Geoffrey C. Ward in Tiger-Wallahs: Encounters With the Men Who Tried to Save the Greatest of the Great Cats.

Battling Poaching

Besides compensation for resettlement, there were limited resources for actually cracking down on poaching and ensuring that the village economy more than just survived.

“Fateh’s friends and supporters would beg or borrow money when he needed it to keep tigers safe. Even money given to the State Governments from the Centre would go to Rajasthan exchequer and would often not be used for wildlife. Forest guards and wildlife were not quite high on the priority list for officials. Most guards lived in the surrounding villages and Fateh did all he could to ensure that they benefited from jobs and livelihoods created to protect the park. He wanted the village economy to be freed from dependence on forest biomass alone. Often money went towards repairing roads and protection trails. Other times it was for the creation of anicuts and other water harvesting systems including step wells from days of yore. He had no sympathy for poachers who would be sent to the police lockup instantly. But through all this, even when tensions were high, he would sit over tea with villagers or share a meal in their villages, while trying to explain why the forest and its wildlife had to be saved,” says Bittu.

Nonetheless, he also took a much more nuanced socio-economic approach to tackling poaching, and a lot of that work happened after he left the forest service in 1996.

“Fateh Singh’s approach to the poachers was unique, and very typical of him. He realised that the people who actually kill the tigers are not the ones who profit from the deed. They are very poor nomadic hunter-gatherers from the Mogiya tribe. Knowing that poaching cannot be curbed by jailing the poachers for a few days and then letting them off on bail to continue their occupation, he has been trying in the recent past to rehabilitate them by offering them an alternative livelihood,” writes Soonoo.

Tiger Watch

After his 10-year stint at Ranthambhore came to an end in 1987, he was appointed as the Field Director of the Sariska Tiger Reserve at the request of then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi, who wanted him to replicate the same success there.

However, that didn’t happen because he came up against a district administration immune to the needs of tiger conservation.

“Just two years later [after my posting there], the collector, all of a sudden, allowed villagers to take their cattle into the park for grazing. More than 20,000 cattle entered the park, threatening the wild animals there. I resigned my job as a mark of protest. Soon I came to know that 16 tigers were missing. I became an eyesore for the forest department. I could understand their follies. I spoke the truth and was quite outspoken. They had every reason to hate me,” he says in a March 2011 interview.

Little surprise that more than a decade later, in December 2004, the disappearance of tigers from the Sariska Tiger Reserve made headlines.

Fateh retired from his official duties in 1996. In the following year, he established the non-profit Tiger Watch, which is today led by his protege Dr. Dharmendra Khandal. One of the primary things he wanted Tiger Watch to do was rehabilitate the Mogiyas, and improve the relationship between them, and the park.

“The Mogiyas are a small community living in the interiors of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh. Their major source of livelihood is poaching and they are so desensitised to the act of killing from a very young age that bringing about a change in mentality of the community was one of the most difficult tasks,” shares Dharmendra speaking to TBI.

However, their efforts to help the Mogiyas only picked up speed after 2004, when a survey conducted by Tiger Watch found that led to the shocking discovery of 18 missing Tigers from Ranthambore. These poachers were the foot soldiers of a vast nexus of wildlife criminals that crossed international boundaries.

“With the help of informants turned and procured from within the Mogya (Mogiya) tribe and active assistance from the local police force, Tiger Watch conducted several raids, and managed to clamp down on several poaching gangs operating in and around the Ranthambhore National Park,” says the Tiger Watch website.

“Tiger Watch initiated the Mogya (Mogiya) Rehabilitation and Education Programme which sought to bring the tribe into the mainstream by ensuring that the next generation received an education and were thus weaned away from poaching. The first to enroll in the programme were the children of the very poachers arrested in Tiger Watch raids with the police. The community, among other things, now has its first ever university graduates,” it adds.

Dharmendra says that busting the poaching racket at Ranthambhore was only the first step to a larger change. And that had to come with education. In 2006, they started the Mogiya Hostel for the community children near the tiger reserve.

Talking about the hostel, Meethalal Gurjar, a teacher, says, “These kids come from very difficult backgrounds, and it is our job to help them have a choice and stay motivated throughout. Sometimes there is a bit of tension from the families, while other times, they are supportive. A lot of them are pushed into the business of poaching by their parents, so this hostel is their safe space to help them navigate through all of that to come out successful.”

Working with the Mogiyas resulted in the Village Wildlife Volunteer Programme.

“Led by a man called Hanuman Gurjar, the 50-member team of village youth help monitor tigers. Overseen by Tiger Watch and the forest department, these pastoral herders are given a monthly stipend and smartphones with memory card adaptors for the camera traps which allow them to report their findings every morning to Tiger Watch via WhatsApp. They operate out of villages in an unofficial buffer zone on the peripheries of the 1,700 square kilometre tiger reserve and have become an unprecedented source of liaison between the forest department and local communities,” notes this GRIN News report.

They also play a critical role in mediating between forest authorities and local communities in the event a herder loses his cattle to a tiger kill to ensure accurate compensation.

Besides initiatives like Tiger Watch, Fateh, along with Dr. Goverdhan also began conducting healthcare camps in the villages through the 1990s, which eventually resulted in the establishment of Sevika Hospital in Sawai Madhopur in 1997.

Today, it’s a super-specialty hospital that specifically caters to low income communities in the surrounding villages. Similarly, the Fateh Public School was also started to deliver quality education to children living in the surrounding villages back in 2001. Both the hospital and school are run by Prakratik Society, a non-profit started by Dr. Goverdhan.

Legacy

Fateh passed away on March 1, 2011 at the age of 72 after suffering from a bout of lung cancer at his home in Sawai Madhopur, and the legacy he leaves behind is immense.

Visit the website of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), a global agency with 134 member nation states, today and there you will find what Fateh knew back in the 1970s – loss of species will make the Indian subcontinent unliveable.

“Scientists and economists have discovered today that forests control the climate, forests harvest water. Species ranging from butterflies and bees to tigers and turtles are the gardeners of Eden. Fateh hated the idea of ‘planting trees’. Why should we plant trees when monkeys, birds and wild pigs do a better job of it by eating fruit and then scattering seeds with their excreta, he never tired of saying,” says Bittu.

When Sanctuary launched its Kids for Tigers educational outreach programme in 2000, Fateh master minded an incredible village contact programme for the magazine.

It started with a Kids for Tigers Festival in Sawai Madhopur that drew in almost 25,000 visitors from near and far. He brought in hundreds of village children who marched through Sawai Madhopur town. One such child was 11-year-old Govardhan Meena from Rawal Village, who is now in his 30s and married with kids of his own.

“Govardhan is now the virtual Pied Piper of Ranthambhore with over 15,000 kids from 45 villages in his vanar sena. These kids are taken into the forest that Fateh nurtured all his life. Many of their parents are now dependent on income from tourism and also from jobs created to protect wildlife. Govardhan does this through storytelling, tiger fests, slide and film shows in their villages. The tiger, he explains, is just a symbol for all of nature,” says Bittu.

One lesson that forest officers should specifically learn from his life is that their loyalties should lie only with the forests and not politicians or superior officers.

“Fateh lived a full and very rich life. His life was entwined with Ranthambhore. In between when he cracked down too hard, ‘the system’ struck back. When he was in advanced stages of cancer he was even prevented from entering the forest he loved, but then his son Govardhan Rathore and Belinda Wright of WPSI, managed to get him to take a last ride into the forest for which he had devoted his whole life. He just wanted to make sure that Ranthambore as a child grew up to be a strapping young adult that could actually survive without him. That was his abiding passion,” he notes.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.