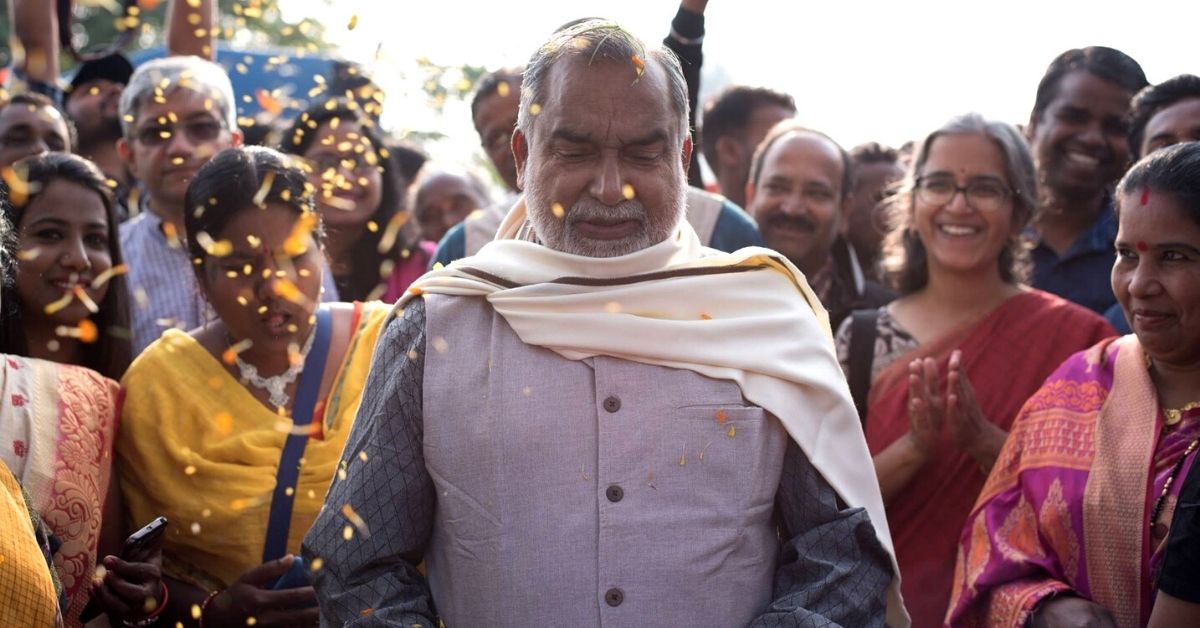

Revered by Nobel Laureates, This Unsung Hero Has Uplifted 2 Million Lives in Odisha

Joseph Madiath was a mere boy of six when he organised the labourers at his father’s rubber plantation. And he hasn't stopped since!

Joseph Madiath was a mere boy of six when he organised the labourers at his father’s rubber plantation in Kuttanad, Kerala, demanding better wages on their behalf. Sent off to a boarding school soon afterwards, Joseph got himself expelled from the institution for creating a students’ union that protected the rights of the students.

At college as well, he came under scrutiny for vehemently advocating for students’ rights, amid a tumultuous political situation in the country.

Today, destiny’s troubled child, Joseph, is a messiah for over six lakh people in Odisha, most of whom hail from remote, underdeveloped tribal districts. He has been closely associated with multiple Nobel Laureates, adopting their discoveries to improve the lives of the rural poor, through this non-profit organisation Gram Vikas.

In an exclusive conversation with The Better India, 69-year-old Joseph revisited his inspiring journey so far, recalling the poignant stories of social inequality that stirred him as a child, as well as the villagers who once resisted his efforts to introduce toilets in their homes.

Appalled by caste discrimination in childhood

Born just three years after Independence, Joseph was an ordinary village boy who grew up running around the village roads and listening to his grandmother’s riveting stories of social discrimination.

In his childhood, he also learnt about his grandfather, a cultivator, sharing lunch with labourers who ate a gruel of rice from a hole dug in the soil. That was apparently the norm of lunch meant for the working-class minorities.

Even Joseph himself was not allowed to play with young children from certain sub-castes in front of everyone.

Appalled by such deep-rooted casteist discrimination around him, a young Joseph grew up to be a rebel with a cause.

The rebel hero who saw the real face of India on pedals

After recurring stints of organising people and conflicting with authoritarian systems throughout his school and college days in Calcutta and Chennai, Joseph decided to embark on a cross-country bicycle tour.

He was inspired by Mahatma Gandhi famously travelling across India in a third-class compartment to see the real face of the country.

“In nearly a year, I cycled through the remote villages and hamlets of India. I was taken aback by the poverty and misery of so many people, especially the people in tribal villages,” he says.

While paddling his two-wheeler, Joseph would dream of working for the betterment of these people one day. Joseph returned to college a changed man — one who organised student volunteers to help the society.

In 1971, when war between India and Pakistan broke out, hordes of refugees from Bangladesh poured into the Indian side of the border, in Bengal. The government sought volunteers to manage the refugee camps and provide relief to them. Joseph created the Young Students Movement for Development — a forum of student volunteers who happily served the ones in distress.

“At that time, a cholera outbreak happened among the refugees in Calcutta. My team was assigned the one task rejected by all — to offer a dignified end to those who succumbed to the epidemic. I would carry the dead bodies in the truck and bury them,” Joseph recalls.

Coming to Odisha…..

The same year, a catastrophic cyclone tore through the coastline of Odisha in October. Back in the day, the state was least prepared for the calamity. Thousands of people were displaced from their homes and needed immediate relief.

“By that time, the refugee relief in Bengal was fairly under control with global help pouring in for them. So, with a team of 40 student volunteers, I travelled to Odisha to help the cyclone survivors,” shares Joseph.

The stark poverty and misery of the coastal state affected Joseph. He also realised that the periodic occurrence of such natural disasters had demoralised the people, who now felt dependent on relief resources instead of starting their lives anew.

In Patamundi block, Joseph organised a cooperative society which motivated the people to cultivate at least two crops a year. The alluvial soil in the region was highly conducive for the same. However, he was met with resistance from the people who asked him to leave when they learnt he was unwilling to be a relief donor forever.

Around the same time, he got a proposition from the then collector of Ganjam district, who invited his team to help support the Adivasi population. “In our analysis, we saw that the tribals were the most marginalised people in the state. We gladly accepted the opportunity, and set up a new organisation — Gram Vikas — in 1979, in Moguda village.” By that time, Joseph had set his mind to stay in the state amidst the lesser privileged communities.

…..And making the state his home

The administration instructed Joseph to train the tribal people in animal husbandry and dairy development, so that they learn modern life skills and can integrate into mainstream society. However, when Gram Vikas volunteers went door to door in the tribal pockets, they learnt that the Adivasis there considered milk extraction from animals a grave sin.

Their forest-based culture respected all animals and believed that an animal’s milk should be reserved only for its offspring. With the first setback, the volunteers decided to consider other ways for their upliftment.

“We realised that the people were in such impoverished state mainly because of unscrupulous money-lenders and landlords, who duped and deprived them often. With the central government promoting the moratorium on bonded labour at that time, we tasted our first victory in the land by securing the tribal lands illegally snatched by these landlords and lenders,” narrates Joseph.

Gradually, Gram Vikas’ operations expanded to other areas of Odisha. Next, they convinced the tribal communities to give up cutting trees for firewood, and use biogas for cooking instead. The Gram Vikas institutional building had installed the first biogas plant in the entire region. Impressed by their success, the government of Odisha once again sought their help to set up similar plants in different underdeveloped villages. Gram Vikas representatives trained engineers, technicians and local people, who collectively managed to set up 59,000 biogas plants in nine years across the state.

Creating Gram Vikas

Today, Gram Vikas has 400 active volunteers, and has positively impacted more than six lakh people in the past four decades. Indirectly, they have impacted more than two million lives.

From biogas to sanitation, water supply to solar power, Joseph and his brigade of Good Samaritans have transformed village after village both in tribal and non-tribal belts.

While conducting a meticulous survey of the living conditions in 100 villages, Joseph realised that the most pressing problem affecting people was ill-health. Recurrent disease outbreaks, stemming from the abysmal attitude towards human waste disposal was responsible for the same. Raw faeces flowed directly into water resources from where it would be collected for drinking and bathing purposes.

Joseph informs, “We created MANTRA — Movement & Action Network for Transformation of Rural Areas through which we wanted to ensure that every family in the village had a toilet and bathing facility at home. Irrespective of their financial status, people should have access to safe water for drinking, coming to their homes from a central overhead tank through pipelines.”

Despite initial objection from people due to conditioning towards primitive habits, Gram Vikas managed to make MANTRA objectives a success. Later, they also helped electrify several villages using solar power. And this is where Joseph’s interaction with Chemistry Nobel Laureate Michael Stanley Whittingham must be mentioned.

“We worked with Michael to see how energy could be stored for a longer time, which could be used for productive purposes, say, pumping of water. Michael developed the Lithium-ion battery that works in solar micro-grids.” Collaborating with him, Gram Vikas installed the invention in several locations in Kalahandi district.

Revered by Nobel Laureates

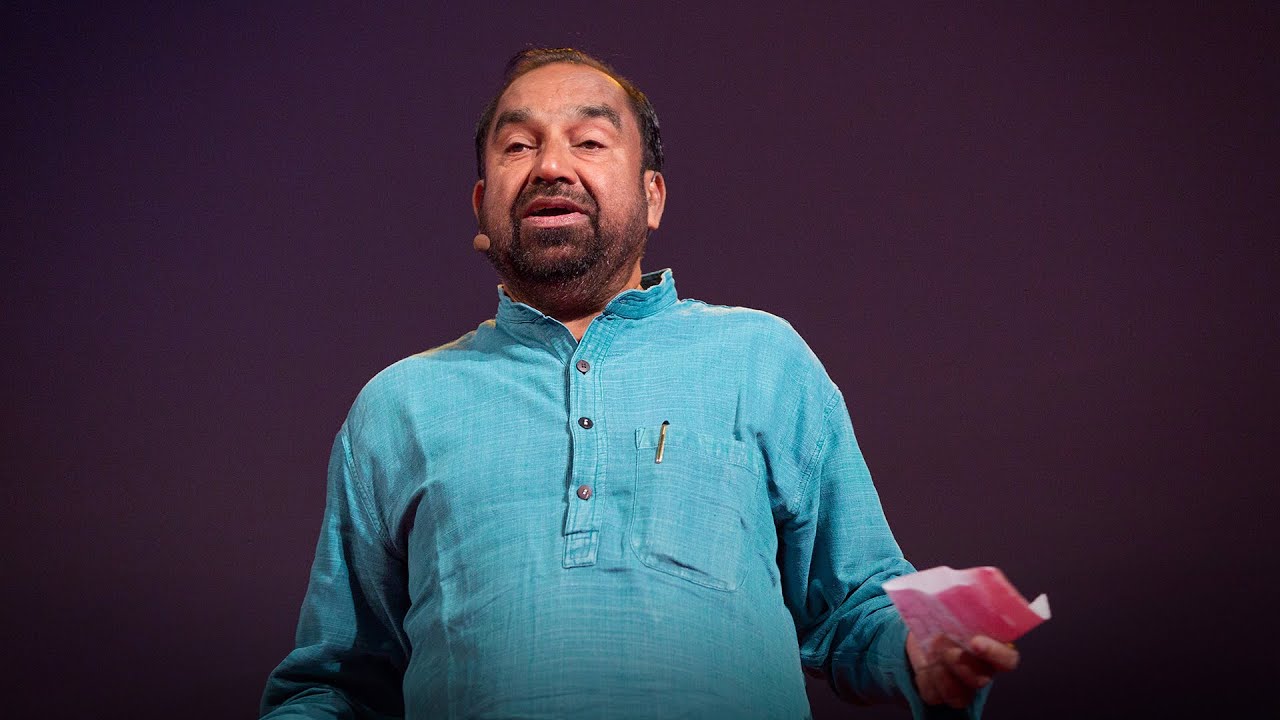

Joseph is also fondly revered by another set of Nobel Laureates — Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee — who won the award in Economics in 2019. The duo has famously described Joseph as, “A man with a self-deprecating sense of humour who attends the annual meeting of the world’s rich and powerful at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in outfits made from homespun cotton.” Joseph also remembers Esther as a dedicated researcher who worked among village communities along with Gram Vikas for a long time.

Liby Johnson, the executive director of Gram Vikas, shares his experience of working side by side with Joseph for nearly an era, “Joe has this uncanny ability to sense what needs to be done in a village. I have learnt greatly from the way he interacts with people, observes and analyses. For example, the way he designed a water supply system for a village making use of a spring in the hills is something a lot of us internalized.”

He continues, “Gram Vikas has done more than 400 such systems so far; every person who does the scouting, planning and designing follows what Joe first did in the mid-1990s. He taught me how to be foresighted and deal with uncertainties that come in your way while working with difficult issues of people’s development.”

“Dr Joseph is a phenomenal mentor and a role model,” says Eshaan Patheria, a Harvard student who worked with Gram Vikas from August 2018 to September 2019 for 13 months as an SBI Youth Fellow.

And about himself and his work, Joseph has only one thing to say, “I am passionate about improving the quality of life of the rural poor. But, my passion alone will not bring the change we need. More people and organisations need to come forward with similar ideals.”

(Edited by Saiqua Sultan)

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.