IFS Officer Helps Solve Man-Elephant Conflict, Villagers Farm Again After 6 Years

“Locals start seeing wildlife and animals as their enemy. Our job is to create a narrative that these animals are not their enemies.”

Nirmala Sawant, the gram pradhan of Gaindakhali, a village in Uttarakhand’s Champawat district, has long held severe concerns about the growing incidence of human-animal conflict in the area.

Her fears aren’t unfounded. Gaindakhali is on the periphery of the Nandhaur Wildlife Sanctuary, which falls under the Haldwani Forest Division of the biodiversity-rich Terai region. In the last 10 years, this place has witnessed over 100 cases of human-animal conflicts, particularly with elephants, resulting in serious crop damage, injury and death.

“Due to the repeated damage and loss of lives, farming and all allied activities had come to a standstill in the village. Our forest officer took cognisance of the problem and reached out to his seniors, who got in touch with Kundan Kumar sir, the Divisional Forest Officer (DFO). After visiting our village, DFO Sir took a survey of the area and installed a kilometre-long tentacle (hanging) solar fence. Thanks to this, we have started farming again. I sincerely feel that the fencing should extend to other villages on the periphery of the forests,” she says.

Mahesh Singh Bisht, the forest officer of the Sharda range, who first took cognisance of the problem, concurs with Nirmala. “As a result of this fence, no big animals cross onto their land anymore,” he says.

Preventing Human-Animal Conflict

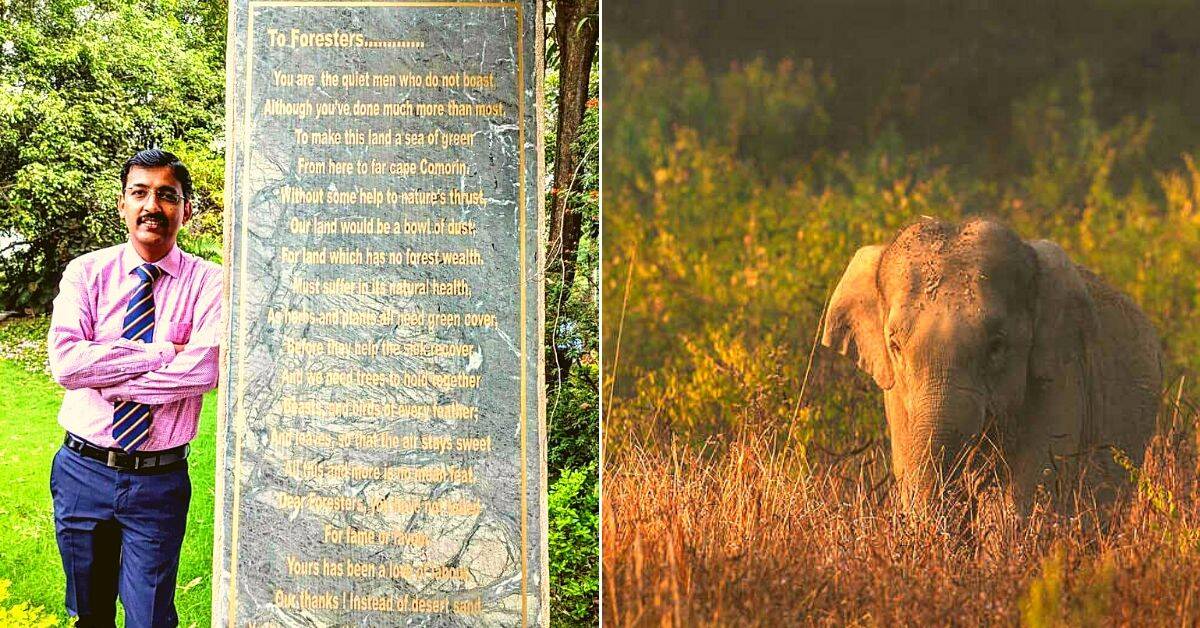

Kundan Kumar, a 2017-batch Indian Forest Service officer, took over as the DFO of Haldwani Forest Division in the last week of November 2019. On his first visit to Gaindakhali, he was alarmed by the severity of the human-elephant conflict in the village.

“The villagers said that they hadn’t planted any crops on their lands for the past six years fearing damage and monetary loss. So, I came up with the plan to install a tentacle solar fence. The initial plan was to install it across 3.5 km, but we began with a 1 km stretch,” says Kundan Kumar, speaking to The Better India.

Following various representations, he decided to survey the village along with his fellow officers. During the survey, his team had first contemplated going with conventional solar fencing consisting of small poles measuring 4-5 feet and between them three-four layers of horizontal wires powered by solar energy.

They found that this method was unsuitable and carried a lot of constraints.

“In setting up a traditional solar fence, you block access to lands beyond the forest. Instead of focussing on our target species (the animal), which in this case is elephants, Nilgai or Sambar deer, these conventional solar fences also block smaller animals like rodents from passing through,” notes Kundan Kumar.

And that’s how they zeroed in on tentacle solar fencing. Construction began in January 2020, and it was completed within the month.

The fence is a robust curtain-like arrangement which has stainless steel wires hanging down vertically from a height of over 15 feet. The wires are suspended from a horizontal steel wire hung from posts planted at a distance. The solar-powered energiser (solar panels) connected to the fence delivers a non-lethal shock to the elephants. These wires are flexible and remain three feet above the ground, allowing forest officers to obstruct their target species, while allowing smaller species to pass through seamlessly.

“Also, if an elephant crashes into a conventional solar fencing structure, and the wire breaks, the entire stretch becomes dysfunctional. Since our hanging wires are very flexible, there is little damage even if the mighty elephant crashed into it. The 12-volt current that passes through these wires is non-lethal, but once an elephant comes into contact with it, they don’t walk past the same area again,” adds Kundan Kumar.

To come up with the ideal length of the wires (tentacles) protruding from the posts to prevent elephants from breaking through, forest officials even took mitigating factors like the size of their tusks and girth into account. They have also developed a fence monitoring system to keep tabs on the voltage discharged by the solar panels, battery and ground conductivity.

Moreover, in traditional solar fencing structures, it’s a real challenge to push elephants back into the forest when they get tangled up with the hard wiring. In this curtain-like structure, however, all forest staff need to do is switch off the electricity and the elephant can comfortably get itself out of it. This system is even more cost-effective.

“The per-unit cost as compared to normal solar fencing, where concrete work is required at the bottom to ensure there is no growth of herbs or shrubs that can damage or short circuit the wires, is also lower. In hanging solar fencing, there is no concrete work. The per km cost of installing a hanging solar fence is 30-40% less than the conventional ones,” he notes.

Before The Fence: Inspiration from Bandipur Tiger Reserve

Kundan Kumar was an officer in training back in 2017 when he went on a tour to national parks and sanctuaries in South India. It was at the Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka when he first saw the effectiveness of tentacle solar fencing.

“Tentacle solar fencing was established in the Bandipur Tiger Reserve in 2017-18. Initially, we had set it up on a trial basis, across 3 km. Today, out of 220 km of our periphery borderline, the fencing stretches around 20 km. It has proven to be very successful and is more than 70% effective in preventing elephants from travelling outside their core area into human habitations on the periphery of the reserve. To an extent, herbivores like spotted deer, sambar and even peacocks are also obstructed. This year, we are going to extend it a further 3 km,” says K Paramesh, Assistant Conservator of Forests (ACF), Bandipur, speaking to The Better India.

The fencing was a result of the human-animal conflict on the periphery of the forest reserve. The locals put forward the demand as they didn’t want elephants or wild boars to enter their fields.

“While most aren’t concerned about the type of fencing, some farmers demand railway barricades to fence the border areas. We were among the first to start this fencing system as well. In Bandipur, these railway barricades stretch to about 40 km. For railway barricading, officials at the reserve utilise rails from the railway tracks and procure it from the railway department. It’s quite expensive compared to a hanging solar fence. However, it is permanent, stable, long-lasting and low maintenance. In hanging solar fences, the wires coated with aluminium will deteriorate after five years and require some degree of maintenance. We may have to replace the wires after 5-6 years,” says Paramesh.

“The cost differential is significant. Railway barricading costs around Rs 1-2 crore per km, while for hanging solar fences, it’s at about Rs 3-3.5 lakh per km. But the problem with these railway barricades is also that they result in a permanent hindrance for wildlife movement,” says Kundan Kumar, explaining why he chose hanging solar fences.

According to a report in The Hindu, “the cost of laying [a] fence for 1 km is Rs 1.25 crore” at the Nagarhole National Park in Karnataka. Although farmers in the periphery of the forest area have reported a steep fall in crop damage as a result of this structure, in December 2018, a male elephant tragically passed away while trying to cross a fence.

Nonetheless, DFO Kundan Kumar took inspiration from Bandipur to start work on the hanging solar fence just weeks after his arrival. Since this was the first time such an installation was envisioned in Uttarakhand, he found out that local vendors did not have the technical know-how to construct this type of fence.

“So, I reached out to vendors in Mysore, obtained some drawings of the structure and its technical details. Then, I called some local vendors and asked them whether they could construct it. I had drawn the structure, explained how this could be made and offered them all the technical specifications for it. After this meeting, I floated a tender with all the necessary specifications, and we awarded the vendor offering the best price,” he says.

Taking Ownership

Over the years, critical elephant corridors, which are not officially notified, have shrunk in the Terai region of Uttarakhand. This has brought elephants closer to human habitats. Therefore, no conservation effort is successful unless the local community doesn’t issue its support.

“The villages on our forest fringe, for example, have suffered from crop raids by elephants crossing over into their land that sometimes results in human deaths. This results in animosity against the elephants. Locals start seeing animals as their enemy. Our job is also to create a narrative and make them realise that these animals are not their enemies. Unless we can make them feel safe, we can’t seek their participation in conservation and protection,” says Kundan.

The fencing they have created is on the border of the reserve forest area. Also, Gaindakhali village isn’t a new habitation. This village has been around for years.

To address the situation at hand, however, forest officials are developing bamboo plantations and grasslands to provide a better habitat for elephants in the reserve forest area. In their plantation, they have grown plant species that elephants like to consume. They also create water holes inside the jungles and thus contain them inside so that they don’t have to venture out.

“We are also creating installations like tentacle solar fencing to protect local communities, who have long demanded it. In the event, wild animals kill someone or destroy their crops or kill their cattle, we give them monetary compensation as well,” says Kundan Kumar.

If maintained properly, this structure can prove to be a long term measure to prevent human-animal conflicts. The one issue is maintenance, but forest officials have collaborated with representatives of the local Panchayat, and given them the responsibility to ensure that there is no wire theft or cutting. “They are willing to take ownership of this facility because they understand that this fence will protect their lives and crops,” he adds.

It has been more than five months since this solar fence was set up and the results have been very positive even though forest officials are conducting on-ground studies to contextualise the results they’re seeing now.

“We are conducting a study on how much compensation we have paid to villagers in the past years for crop damage, injury, and deaths as a result of human-animal conflict. But based on the first-hand feedback, locals feel safer,” says Kundan Kumar. Gaindakhali villagers had not sown paddy or wheat in the past six years. Now, they have got back to their agricultural activities thanks to the work of this forest officer.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167