Labourer to Liberator: The Forgotten Hero Who Helped End Colonial Slavery in India

“That the British were instrumental in creating a slavery system should be known to all. And when that story is told, Totaram Sanadhya’s story is bound to come up.”

While slavery was formally abolished by the 1830s in British colonies, what came in its place was a system of labour that was as bad if not worse.

“As for slavery, which ended in British colonies by the 1830s, the plantation islands ruled by Britain started experiencing severe labour shortages, especially with the reluctance of former slaves to continue as wage labour at the rates that prevailed during slavery. With the planters failing to turn labour powerfully into a commodity, they sought ‘an alternative and politically acceptable form of unfree labour’, which was to be found in the indentured population from British colonies like India,” writes Sunanda Sen, in a 2016 academic paper published in Social Scientist, a journal published by the Indian School of Social Sciences and Tulika Books.

The British colonialists established the indentured labour system in 1838 as a cheap source of labour to their colonies after the formal abolishment of African slavery in 1833.

“Indians, under an ‘indentured’ or contract labour scheme, began to replace enslaved Africans on plantations across the British empire, in Fiji, Natal, Burma, Ceylon, Malaya, British Guiana, Jamaica and Trinidad,” says this explainer in the UK National Archives.

This practice was not merely restricted to British colonies. French, Dutch and other European colonies that had large plantations also fully utilised the harsh economic and social conditions in India to lure the dispossessed into their trap.

Some estimates suggest that nearly 1.2 million Indians were displaced from their native land to the colonies between 1838 and 1916 under this system. These labourers were popularly known as ‘girmitiyas’, which is derived from ‘girmit’, a corrupt form of the English word ‘agreement’.

The terms of this agreement stipulated that the labourer would not pay for his passage to a foreign land where they would end up working, but instead agree to provide labour for a fixed period in return.

Everything from wages, work hours, housing and medical facilities was specified in these ‘agreements,’ which prima facie, appeared fair, but in reality, were exploitative and tapped into their desperation for work.

So, in many ways, what primarily emerged was a system of bonded labour or what some have called ‘second slavery.’

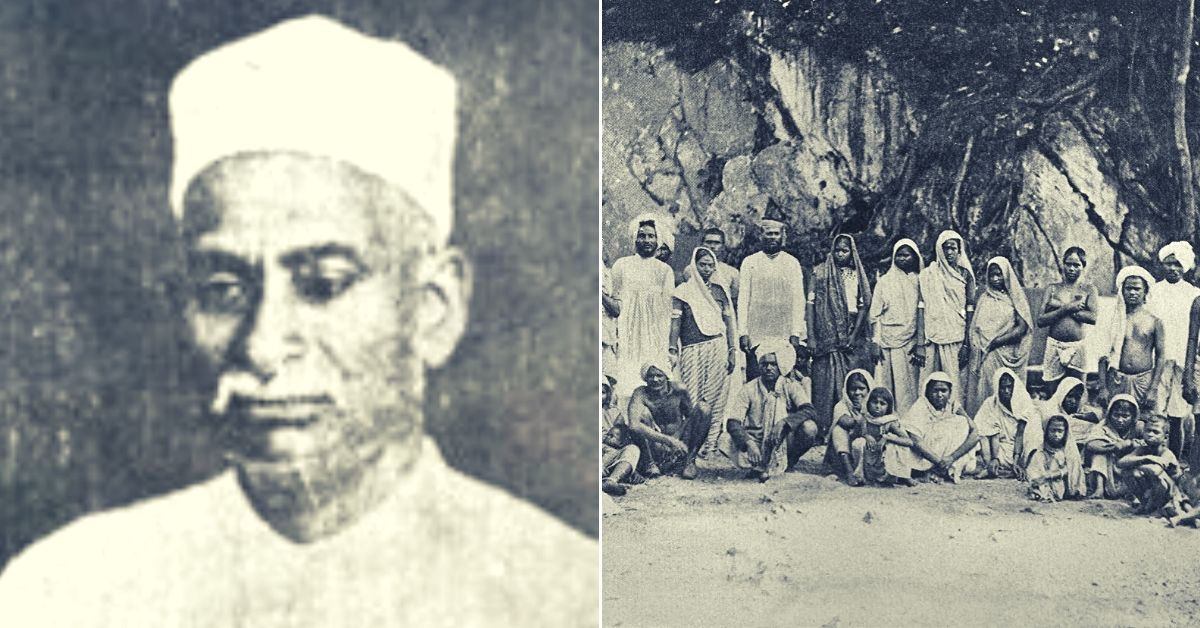

The Story of Totaram

Totaram Sanadhya was one such girmitiya who landed in the sugar plantations of Fiji in May 1893. By the time he arrived, about 12,000 labourers had already made the voyage. By the time he left the island, he was accompanied by nearly 61,000 of them.

Born in 1876, according to his account published as Fiji Dveep Mein Mere Ikkis Varsh (My Twenty-One Years in Fiji), Totaram was a native of a village near Firozabad in present-day Uttar Pradesh.

Barely 11 when his father passed away, Totaram and his brothers had no option but to earn a living. Leaving home in 1893 in search of work, he was lured in by an arkati (recruiter) near Allahabad looking for labourers willing to work in a foreign land.

“Look, brothers, the place where you will work you will never have to suffer any sorrows. There will never be any kind of problems there. You will eat a lot of bananas and a stomach full of sugar cane, and play the flute in relaxation,” said the arkati according to Totaram’s account.

Desperate for work, Totaram signed up.

Three days later, he was among the 165 people brought before a magistrate, who just asked them whether they had agreed to go to Fiji or not and processed their applications. The entire session lasted only 20 minutes, and the magistrate made no effort to explore the matter any further. There was nothing said about the terms of employment to the workers except for the vague promise of 12 annas per day as they were about to board the ship in Calcutta.

When Totaram reached Nausori, the small plantation colony that became his home for the next few years, he knew the arkati had sold him a mirage.

Living in squalid quarters infested with rats and mosquitoes, the food rations he and his fellow recruits received were miniscule, as compared to the back-breaking work expected of them.

There were times when he felt suicidal, but he found solace in reading texts like the Mahabharata and Bhagavad Gita. Eventually, others within his girmitiya community began to address him as ‘Panditji’ as he would narrate tales to them from these epics.

Despite all the hardships, he found a way to survive.

“Girmitiyas were eligible for promotion during their labour tenure and some land once their contract ran its course. Totaram was a smart man who got his promotion when he was under contract and also claimed his right to land once his tenure was up. He also had business acumen and hence soon became a prosperous farmer. That he was a natural leader of man is evident from the way his life panned out,” says Karthik Venkatesh, Consulting Editor at Westland Books, who has in the past written on the subject, to The Better India.

From a labourer, he was promoted to the position of ‘sirdar’ (overseer), married the daughter of a fellow-labourer, eventually earned his freedom and became a sugarcane farmer.

Agent of Change

Using his newfound position and influence in the Indian community on the island, he began meeting other labourers and taking note of how they suffered from poverty, starvation, misrepresentation by the arkati and horrible working conditions.

Taking notes from his own experience as well, Totaram understood that this system was as exploitative as slavery which stripped many of his fellow Indians of their dignity.

In 1910, he issued a petition urging the British authorities to establish schools for the children of girmityas and sought greater representation for the Indian community in the Fiji Legislative Council. Fortunately, around the same time, the popular opinion against this exploitative system of labour had dramatically turned back in India, notes this Firstpost column.

Two years after his petition, a news story appeared in the Bharat Mata publication narrating the story of Kunti, a woman who escaped sexual assault by her overseer by jumping into a river.

Although she was saved, the story outraged many Indians, and several leaders of the freedom struggle repeatedly spoke out against the girmit system in the press and their multiple representations to the Viceroy. During the same year, Totaram and a few others wrote a letter to Mahatma Gandhi asking him to send a qualified English-speaking lawyer to the island in helping organise Indian labourers there.

By December, Manilal Maganlal Doctor had arrived and ended up winning multiple concessions on behalf of Indians living there and overseeing the abolishment of the indentured labour system itself before he was finally deported from the island in 1920.

Totaram, meanwhile, returned to India in 1914, and his published work, alongside an extremely critical report by CF Andrews and WW Pearson, forced the British colonialists into abolishing this exploitative system of labour in 1917.

However, as a consequence of this system, there are many Indian communities settled across the Caribbean islands, South Africa, Mauritius, Fiji and even Malaysia, who have now lived there for generations.

In 1922, Totaram joined the Sabarmati Ashram and passed away in 1948.

“The story of the girmitiyas is one of pain and deprivation to start with. But in time, many of their descendants have done very well for themselves. Totaram’s story is important because his was a life of resistance, not one of passive acceptance. That the British were instrumental in creating a slavery system should be known to all. And when that story is told, Totaram’s story is bound to come up since he played a key role in ending that system. He is akin to a second Abraham Lincoln, in a manner of speaking. The message and legacy of his life is to resist injustice, oppression and demand liberation,” says Venkatesh, speaking to The Better India.

While Totaram may not find a place among the giants of the Indian freedom movement, his contributions towards bringing an end to the second wave of slavery must never be forgotten.

Also Read: ‘Why Should We Be Dumb?’ How One Monk’s Speech Changed The History of Ladakh

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167