Publisher of Ghalib, This Forgotten Pioneer Sparked India’s Love For Printed Books

He was among a handful of those who commercialised printing and was responsible for the dissemination of the printed text at affordable prices, thereby democratising access to knowledge, literature and science.

The history of printing in India dates back to 1556 when Jesuit missionaries from Portugal set up the first printing press in Goa. In 1577, Doctrina Christam, a Tamil translation of a Portuguese text was published – the first for an Indian language. But for the next two centuries, even as Europe gravitated towards the printed text, the press as a modern scientific invention found few takers in India.

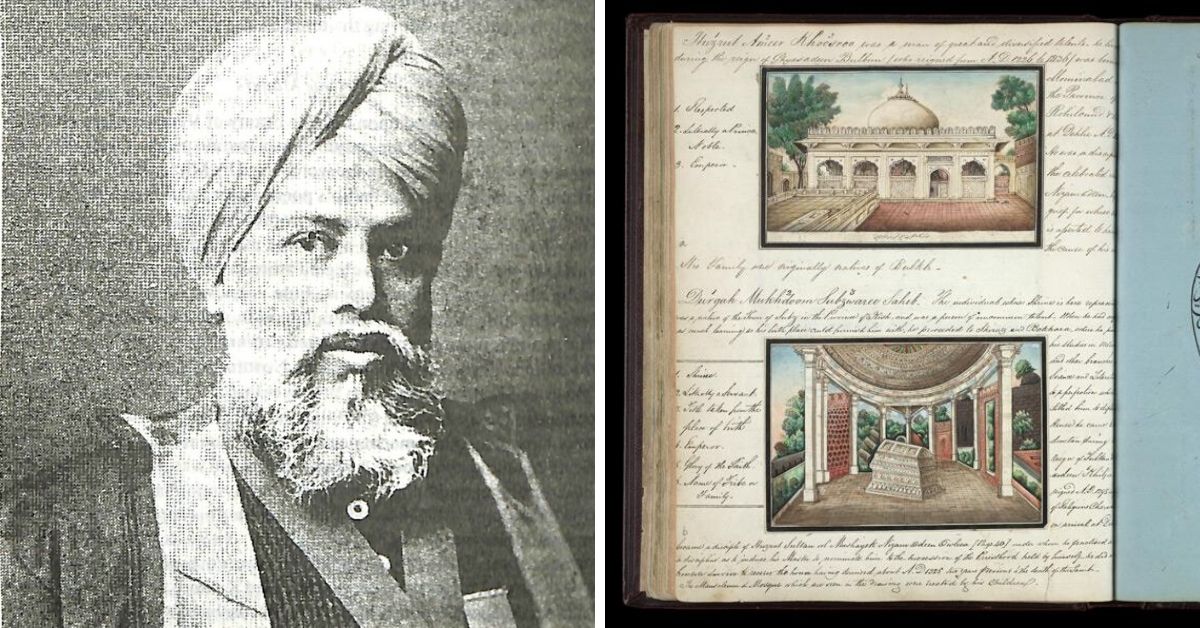

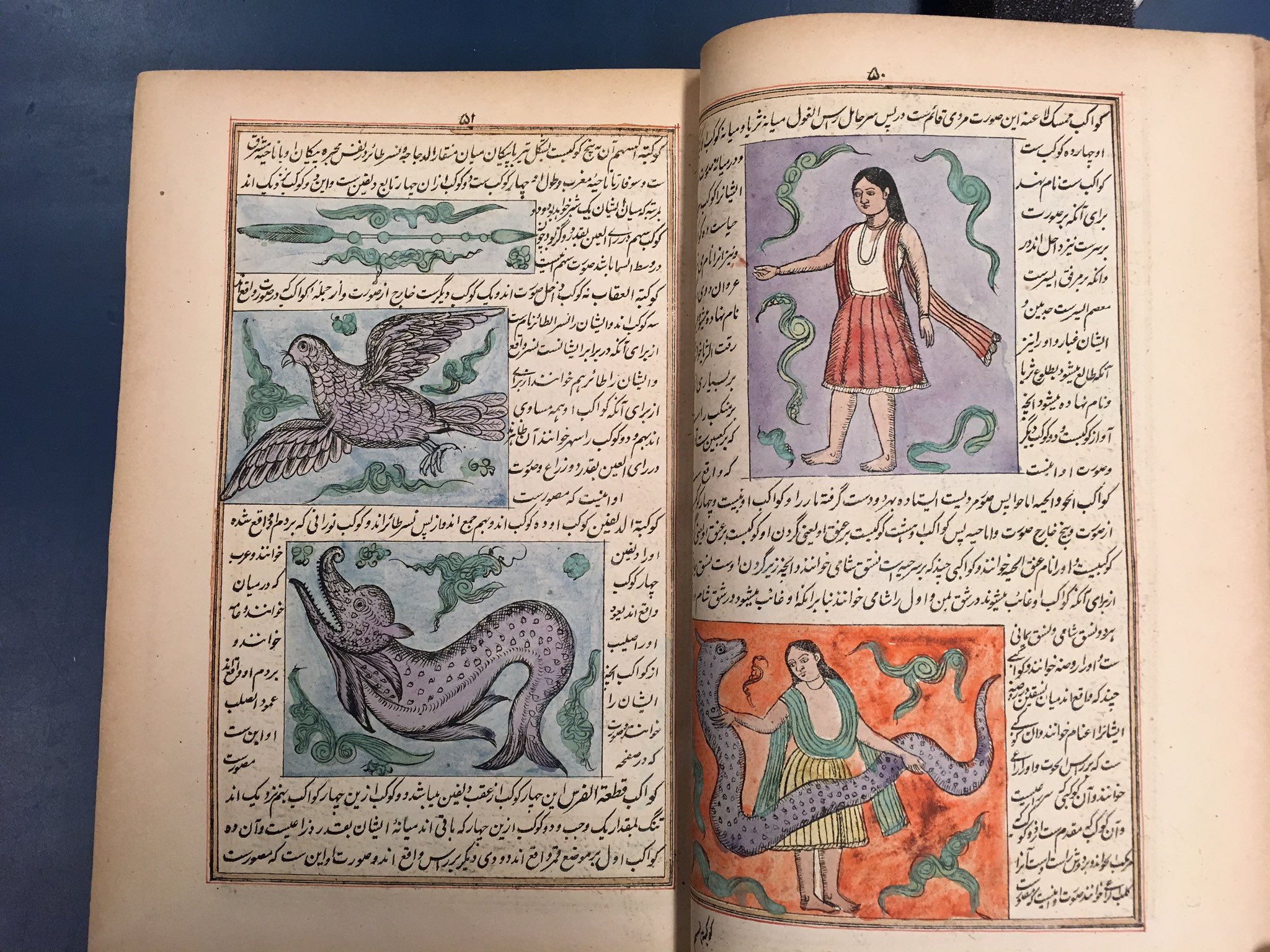

Scholars opine that in Mughal times, the production of beautifully calligraphed and illustrated manuscripts held sway and was preferred to the arguably unattractive printed text. And hence, the inability of this machine to make any headway.

The press, therefore, only began to gain popularity towards the end of the 18th century, when missionaries began to produce texts for proselytisation and instruction. Soon, Indians came to realise the power of print, and by the second half of the 19th century, the medium took on a mass form with many Indians operating presses.

This commercialisation of print revolutionised reading, publishing, and the availability of printed matter to a public that was becoming more literate. In time, the print medium would assist in the creation of a national consciousness that would eventually come in handy to overthrow British rule.

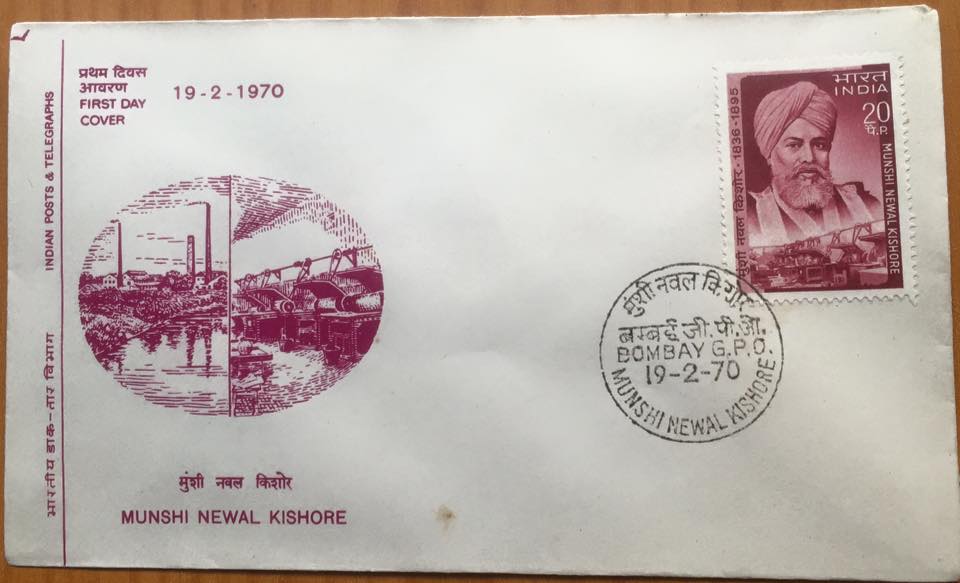

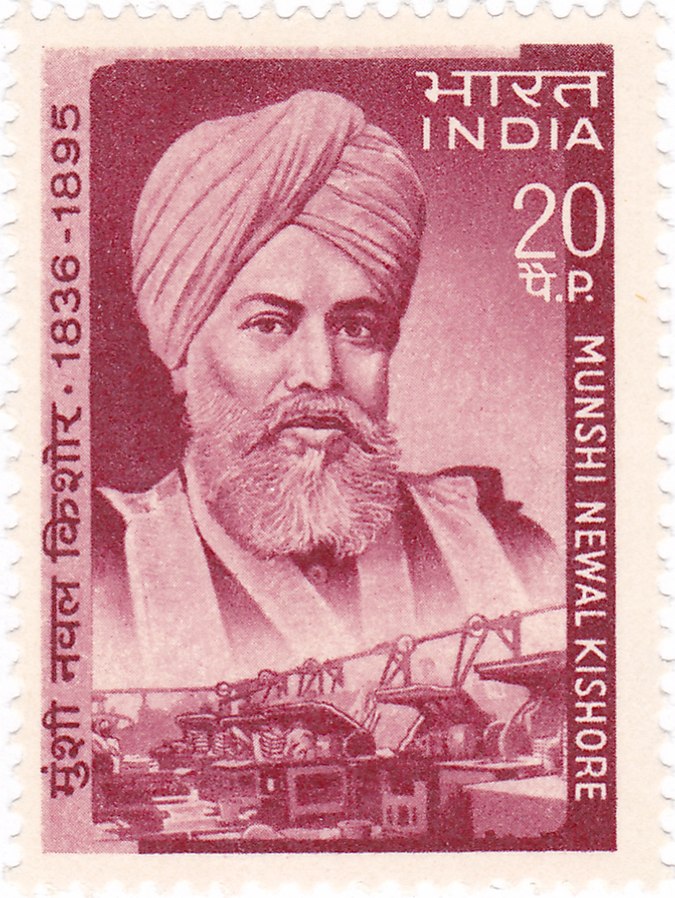

Munshi Nawal Kishore (1836–1895) was not a pioneer of the print medium. He wasn’t a famous author who inspired many to read, nor was he an early Indian nationalist who mobilised the medium for resistance against British rule. Still, his name deserves to be remembered for his role in helping writers, readers, and the broader public realise the potential of print, and thereby ignite something of a revolution.

He was among a handful of those who commercialised printing and was responsible for the dissemination of the printed text at affordable prices, thereby democratising access to knowledge, literature and science. That much of his printing output was in Hindi and Urdu also contributed to this process, which is among the 19th century’s most significant developments but often glossed over.

What could have prompted this early publishing pioneer to gravitate to this career? How did his firm – Nawal Kishore Press – come to dominate the North Indian printing scene for decades?

While Munshi Nawal Kishore’s story is a peek into how northern India’s social and political dynamics were altered under British administration, his is also a story of individual enterprise—an early example of entrepreneurial zeal and ambition.

Nawal Kishore’s ancestors, whom he could trace back to the 14th century, were Sarkari babus. Many of them served the Mughals, (briefly, even the Marathas) in various positions and were endowed with jagirs for their exemplary service. It was at the site of one such jagir – in Sasni, near Aligarh – that Nawal Kishore was born in 1836.

There was a tradition of Sanskrit scholarship in the family, and the young Nawal Kishore showed early promise in this direction. The family’s Mughal connections meant that Persian was also within their ambit, and so, Nawal Kishore was reared in this shared cultural tradition. He was enrolled in the Agra College in 1852 and records indicate that he learnt English in addition to Persian at this renowned institution.

But for reasons unknown, he never graduated.

Instead, in 1854, he left for Lahore and became an employee of the Koh-e-Nur Press, which, among other things, also published Koh-e-Nur, Punjab’s first Urdu newspaper. This apprenticeship which lasted till 1857 (with a break in between) was the beginning of something momentous, as it taught him the ropes of what would become his future career.

In early 1856, Kishore returned to Agra and briefly ran a newspaper of his own – Safir-e-Agra. Later that year, he returned to Lahore and stayed there till the end of 1857, when he went to Agra.

It appears that he managed to win favour with the British by approving of colonial rule at this time. Given that he was associated with a press, this piece of information was bound to have reached British ears.

It is tempting, at this juncture, to dismiss him as a British crony, but his attitude wasn’t any different from those of many in the professional classes who feared the instability that the British exit might bring. In any case, he used this to his advantage. With most old presses shut and his loyalty beyond doubt, Kishore was the right person in the right place at the right time.

A few months later, in 1858, he proceeded to Lucknow, which was a city in ferment at the time. The British had taken over, and this had upset the economic organisation of the city. But in the cultural sphere, the city retained its preeminent position.

In November 1858, Kishore set up his printing press with the official approval of the British. Awadh Akhbar, North India’s first Urdu newspaper, was launched. While the newspaper was one visible aspect of the press’s work, soon, the administration was sending considerable official printing work his way. In 1860, he was handed over the contract for printing the Indian Penal Code in Urdu.

A steady stream of textbook contracts soon followed, and in 1861, he was authorised to print and sell Jami al-favaid, a compilation of conversion tables and tables of weight measures.

Kishore’s association with many Muslim officials in high government positions meant that he was never short of advice when he looked to diversify from mere printing to publishing. Popular religious tracts and extracts from the Quran constituted Kishore’s foray into commercial publishing.

Around this time, Kishore also approached Mirza Ghalib, intending to publish his poetry. After some initial hiccups, the Nawal Kishore Press soon became Ghalib’s publisher. By 1869, the press also published Mirat al-Urus by Nazir Ahmed, acclaimed as the first novel in Urdu.

But the decade’s most sensational event in the world of printing and publishing was the press’s decision to publish a moderately priced version of the Quran—priced at a rupee and a half—which brought the holy book within reach of ordinary Muslims.

Parallelly, even as it had established itself as the pre-eminent Urdu publisher of the region, the press also made considerable contributions to Hindi publishing. Hindi then was a language in the process of becoming concretised. Its progress was impeded by several tussles: Hindi-Urdu at one level, Hindi-Braj at another level, and disagreement about the script—Nagari, Kaithi or Persian. Still, the press saw merit in entering this murky arena.

Among the Hindi books the press produced in the 1860s, were Tulsidas’ Ramacharitmanas (which by 1873 had sold 50,000 copies), Surdas’ Sur Sagar, and Lalluji Lal’s Premsagar (among the earliest works in what is recognisably modern Hindi).

In 1880, the press published an English work – a translation of Tulsidas.

As the press added more titles to its ever-growing list, it had close to 3,000 titles by the late 1870s in its catalogue–in Urdu, Hindi, Persian and Sanskrit, mainly with a smattering in Arabic, Pashto, Marathi and Bengali. Many of these titles were, of course, works of literature. Still, many of them were translations from English, books on science, medicine and history–indicative of Nawal Kishore’s world-view which chose to embrace modernity and not resist it.

In 1877, Awadh Akhbar became a daily newspaper. The Nawal Kishore Press opened several branches – in Kanpur, Gorakhpur, Patiala and Kapurthala – and even maintained an agency in London. In addition to publishing and bookselling, his Press was an early marketing and advertising pioneer.

Across North India right up to then Calcutta, the press operated several bookstores. It advertised these bookstores in its books and newspaper. Then, it used the books it published to advertise its catalogue as well as encouraging other publishers to advertise their offerings in its newspaper which also was a natural outlet for publicising the press’ books.

Apart from running a business, Munshi Nawal Kishore also found the time to serve on the municipal committee of Agra College, the board of his alma mater, and patronised many caste organisations as well as educational institutions, both Hindu and Muslim.

Also Read: How a British Sea Cadet Set Up India’s Oldest Surviving Bookstore

By 1895, when Nawal Kishore passed away due to heart failure, the press he had established was a highly profitable business venture with considerable influence in the cultural sphere. By then, it had influenced a taste in reading and writing which was to change the first half of the 20th century when opposition to British rule was fostered through the press and the actions of the reading public, with many of whom probably having their first taste of the printed text in a Nawal Kishore Press publication.

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

Featured image sources: Wikimedia Commons and Rare Book Society of India/Facebook

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.