‘We Shall Die to Awaken The Nation’: Bagha Jatin, Whose Bravery Shook the British Raj!

Charles Tegart, the legendary police officer of the Empire, once told his colleagues that if Jatindranath were an Englishman, his statue would have been built next to Nelson’s at Trafalgar Square.

Siliguri, Bengal, 1907: It was a crowded railway platform. A man was rushing to his compartment, bringing water for a sick co-passenger, when he accidentally brushed past a British captain. With usual disgust for the natives, the captain swore and hit the man with his cane. A while later, the man returned to demand an explanation of the captain’s behaviour. Three more soldiers came ahead to attack him in response. Within minutes, he thrashed all four on the platform.

Later, in a courtroom, the soldiers were admonished for pressing charges, because nothing could be more harmful to the British reputation than to admit that English military officers were knocked out by one Bengali young man.

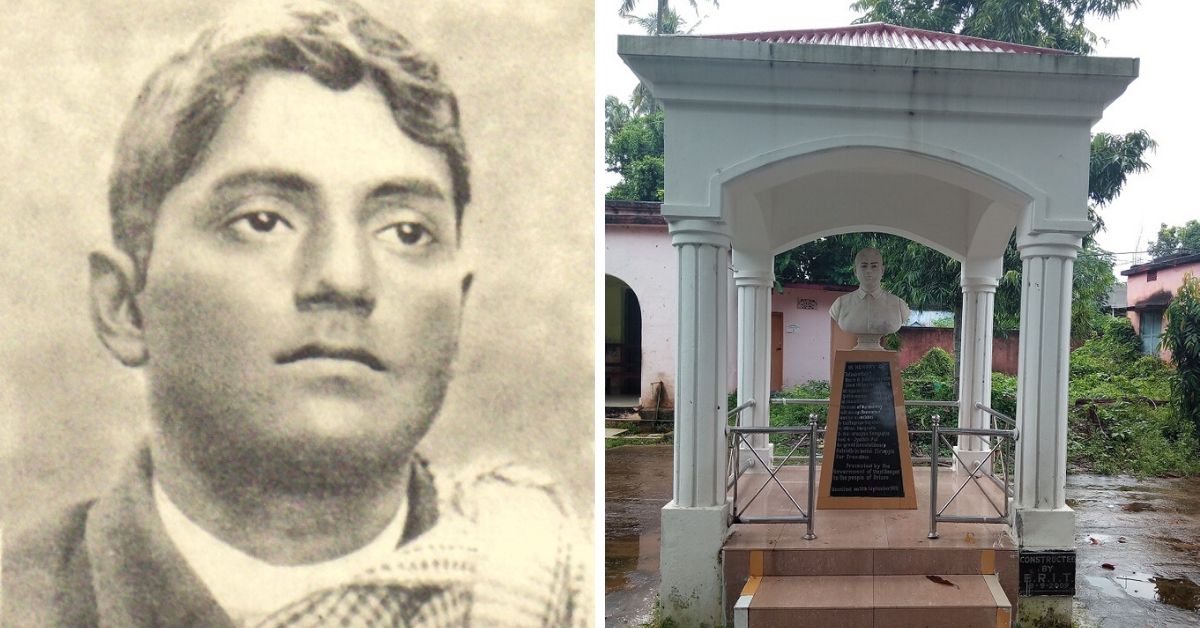

Meet Jatindranath Mukherjee, the trailblazing Indian, who laid down his life in guerilla warfare against the British Empire.

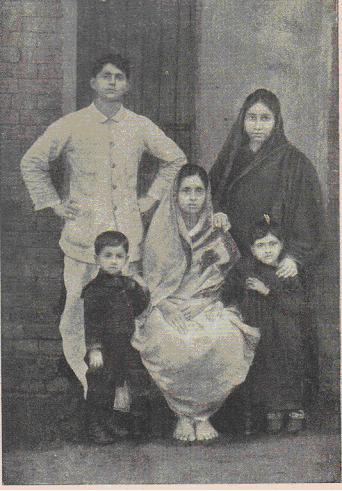

Born on 7 December 1879, in Kushtia of Bengal Presidency, Jatindranath lost his father at a tender age and was raised in his maternal home. His mother, Sharatshashi, was a dedicated social worker, a poet, and a loving but strict woman, who ensured her child grew up to be a strong, courageous and selfless man.

When he was working as a cleric under Financial Secretary Henry Wheeler, he would keep the inadequately small portion of his salary to send to his wife Indubala and his widowed elder sister Binodbala, while the rest quietly went to persons in need. Vivekananda’s idea of patriotism as the only religion, and character-building as the way of worship, inspired him. Later, he became a disciple of Bholananda Giri, who worked towards spiritual upliftment by establishing education centers and old-age homes.

Racial violence shook Calcutta frequently because the British used the whips against ordinary Indians quite freely. Whenever Jatin was present in such a scene, the situation was first dealt with politely, followed by a show of force.

In 1903, Jatin accepted Aurobindo Ghose’s project of organising a secret society aimed at an armed uprising all over India.

In 1905, people of Calcutta were on the streets in a grand procession celebrating the visit of the Prince of Wales. Near the prince’s coach, stood a carriage with Indian ladies. On its roof, some Tommies sat dangling their feet over the passengers’ faces. Upon noticing this, Jatin went ahead to warn them, but was met with obscene comments. So he jumped on the roof to slap each of them off to the ground, making a point before the public and the Prince.

The numerous incidents could be fitted in a pattern–the statement of the clenched fist against the likes of the colonial officers. He stood up to injustice, no matter how menacing the opposition. Wheeler once asked him about how many men he could fight alone. Jatin replied, “I can’t win against even one man if he’s righteous, but I am blessed to be able to take down plenty of the wrong sort.”

The most intriguing anecdote of his early life was how he earned his moniker, ‘Bagha’. In 1906, a Royal Bengal Tiger was roaming near Jatin’s native village in Koya. Disturbed by approaching men, the tiger attacked Jatin’s cousin; Jatin then tackled the tiger into the ground. Following a long wrestling combat, a viciously injured Jatin managed to take out a small Gorkha dagger and stabbed it to its death.

Lt Colonel Dr Sarbadhikari who treated him back from the jaws of death, published an article about him in the English press and named a battalion of Indian soldiers after him. The incident commanded attention, and people started calling him ‘Bagha Jatin’, meaning ‘Jatin with the prowess of a tiger’.

The Government of Bengal awarded him a silver engraving of the scene. By then, Jatin’s emissaries like Taraknath Das, Guran Ditt Kumar, Surendramohan Bose were already creating a base for patriotic Indians in the United States, publishing periodicals with revolutionary literature.

By the time the police formed a chargeable offence against him, a lot had happened in the political landscape of Bengal. Swadeshi and Boycott movements following the Bengal Partition of 1905 were in full throttle. Aurobindo was recently acquitted from the Alipore Bomb Case (1908), while several other co-conspirators from the secret society ‘Yugantar’ were sentenced to imprisonment in the Cellular Jail. Four revolutionaries were already martyred in the gallows by 1909, and some others died in the actions.

As a consequence, Jatin and his network came under scrutiny, orchestrated by Shamsul Alam, the Deputy Superintendent of Police, who had a special talent for torturing and extracting information from captive revolutionaries.

On 24 January 1910, he was killed by Birendranath Dutta Gupta, as per Jatin’s instructions. Birendranath was captured almost instantly, and for the first time, Jatin was arrested by ACP Tegart. After a quick trial, Birendranath was hanged on 21 February. The Howrah-Shibpur Conspiracy case went to trial with 47 revolutionaries being prosecuted, but due to lack of satisfactory evidence, thanks to Jatin’s way of decentralised organisation, most of them were acquitted.

The 10th Jats Regiment in Fort William of Calcutta was suspected to be sympathetic to the nationalist cause due to infiltration by Jatin’s men, so it was promptly dismantled. But due to lack of significant evidence, Jatin was released from jail the following year. Having lost his job, Jatin went back to his native home at Jhenaidah as a contractor for the railway lines. The work involved making frequent trips on horse-back: a perfect cover for his reorganisation of the secret societies.

In 1912, Jatin met the German Crown Prince during his visit to Calcutta and received a promise about firearm supply in India. Rash Behari Bose, involved in an almost successful attempt of killing the Viceroy Hardinge in his Delhi Durbar on that very year, came into contact with Jatin during his flood-relief work in Bengal. He was greatly inspired by Jatin’s plans of a mutiny to uproot British rule.

In 1913, leaving Eastern India under Jatin’s able leadership, he went North to continue integrating the army barracks for insurrection.

In the wake of the First World War on 26 August 1914, a consignment of arms reached the Calcutta gun dealers Rodda & Co. Shrish Mitra, a clerk, entrusted with clearing the shipment, pulled off a heist, disguising a fellow revolutionary as a cargo cart-driver. Thanks to this ‘Greatest Daylight Robbery’ as called by The Statesman, Yugantar got 50 Mauser pistols with 46,000 rounds of ammunition distributed among the top factions.

The ‘Hindu-German Conspiracy’ was inevitably set in motion after the 1914 Komagata-Maru shooting incident. An international pro-India committee with the support of the German Government was established in Berlin, led by Virendranath Chattopadhyay, linked to the U.S. Ghadar Party and Yugantar in India. Rash Behari’s mutiny attempt with Ghadar in February 1915 was thwarted. But Jatin, in charge of the Eastern Zone, including Fort William, was still waiting for the consignment of German arms to arrive.

With four young revolutionaries named Chittapriya Raychaudhury, Nirendranath Dasgupta, Manoranjan Sengupta, and Jyotish Chandra Pal, Jatin set off to Balasore, in present-day Odisha, where the two German ships – Annie Larsen and Maverick – were to arrive with ammunition. A shop named ‘Universal Emporium’ was set up in Balasore to maintain communication, while they moved into two hideouts near Mahuldiha and Taldiha, mingling with the locals, helping them in distress.

Unfortunately, information was leaked via foreign spies. The British Government intervened, stopping both ships from ever reaching the Indian east coast.

Hearing the news of the ultimate scheme crashing to ruins, Jatin smiled and commented, “country’s salvation…from within, not from without!” When asked by senior members to flee and hide thereafter, he refused, saying, “We shall die to awaken the nation.” None of his four followers agreed to leave his side. They left towards the city. The police arrived at their old residences, and announced fat rewards for handing over the “German dacoits”.

The five walked for miles, crossing muddy fields and the furious monsoon river Budi Balam, frequently challenged by the suspicious locals who kept following them, greedy for the rewards. The five had to threaten and occasionally fire their pistols to get away until they finally found what they were looking for: a natural trench to fight from.

In a lonely patch of field in Chashakhand of Balasore, on 9 September 1915, the five men set their final war ground. They righted their Mauser pistols with the detachable wooden shoulder-stocks to set them like long-range rifles, and hid in the trench, waiting for the armed police.

Due to the technical advantages of the trench, the injuries began with the police who climbed up the mound, thinking that the opponents merely had revolvers. After almost an hour of the police battalion’s efforts, a bullet hit Chittapriya’s chest. Injured in the right hand but still firing with the left, Jatin pulled him on his lap. Chittapriya became the first martyr of “The Battle of Budi Balam”.

Ammunition was running out, Jyotish was wounded, and Jatin was shot in his abdomen. He ordered his disciples to surrender, and said, “you are to stay… and tell our brethren, we were not dacoits”.

Jatin was taken to the Balasore Government Hospital, where the following morning, at the age of 35, he breathed his last. Before death, he gave a statement taking full responsibility for the actions and asked for fair treatment towards his innocent followers. Nirendranath and Manoranjan, 23 and 16 at the time, were sentenced to death two months later. They made a speech from the gallows, declaring their purpose and fulfilling their leader’s last request.

Before dying in imprisonment in 1924, Jyotish wrote their story on the cell walls with a piece of charcoal.

Also Read: The Untold Story of India’s 14-YO Female Revolutionary & Her Historic Trial

Charles Tegart, the legendary police officer of the Empire, was heard to tell his colleagues that if Jatindranath were an Englishman, his statue would be built next to Nelson’s at Trafalgar Square.

M.N.Roy wrote, “…I have had the privilege of meeting outstanding personalities of our time. These were great men. Jatin-da was a good man, and I still have to find a better… Jatin-da was a humanist ─ perhaps the first in modern India.”

Data Credits: Sadhak Biplabi Jatindranath, ‘The Intellectual Roots of India’s Freedom Struggle (1893-1918)’.

Special thanks to the author, Dr Prithwindra Mukherjee.

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

Featured images courtesy: Dr Prithwindra Mukherjee and Aishi Roy

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

Similar Story

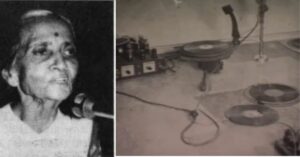

When a 22-YO Ran a Secret Radio Station for India’s Freedom: Usha Mehta’s Biopic

In the upcoming biopic Ae Watan Mere Watan, actor Sarah Ali Khan will essay the role of freedom fighter Usha Mehta, who ran a secret radio station at a crucial point in India’s freedom struggle.

Read more >

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167