The Goan Doctor Who Risked His Life to Treat 18,000 Mumbaikars From Bubonic Plague

Himself tending to patients at great personal risk, Dr Viegas also launched an intense campaign to clean up Mumbai’s slums and exterminate rats, which he knew, were carriers of the disease. #ForgottenHeroes

With the World Health Organization recently declaring the deadly Coronavirus a global pandemic, many historians have harked back to the year 1918. It was a time when an influenza virus devastated vast swathes of the country resulting in the death of an estimated 10-20 million Indians and have spoken about the lessons we can learn from it.

But few have spoken about the Bombay Bubonic Plague in the late 19th century, which killed thousands in present-day Mumbai and resulted in a drastic drop of its population with many residents fleeing. Nonetheless, standing in the frontlines against these deadly diseases are doctors and health workers who risk their own lives to save others.

One such medical practitioner during the Bubonic Plague in Mumbai, who risked his life was Dr Acacio Gabriel Viegas, who is not only credited with the discovery of the outbreak in the city which helped save many lives, but also the inoculation of nearly 18,000 residents despite serious risks to his own health.

Born on 1 April 1856, in the village of Arpora, Goa, Dr Viegas left for Mumbai after completing his primary education. Following his matriculation, which he passed with distinction, he enrolled with the Grant Medical College.

“In the course of a few years after graduating as a medico, Dr Viegas developed a lucrative practice at Mandvi, Bombay, gaining considerable popularity with his large clientele, and in 1888 was elected to the Bombay Municipal Corporation for five consecutive years. He was the first Goan to be so elected,” writes J Clement Vaz in his book titled ‘Profiles of Eminent Goans, Past and Present’.

It was in September 1896, when Dr Viegas detected the first case of Bubonic Plague.

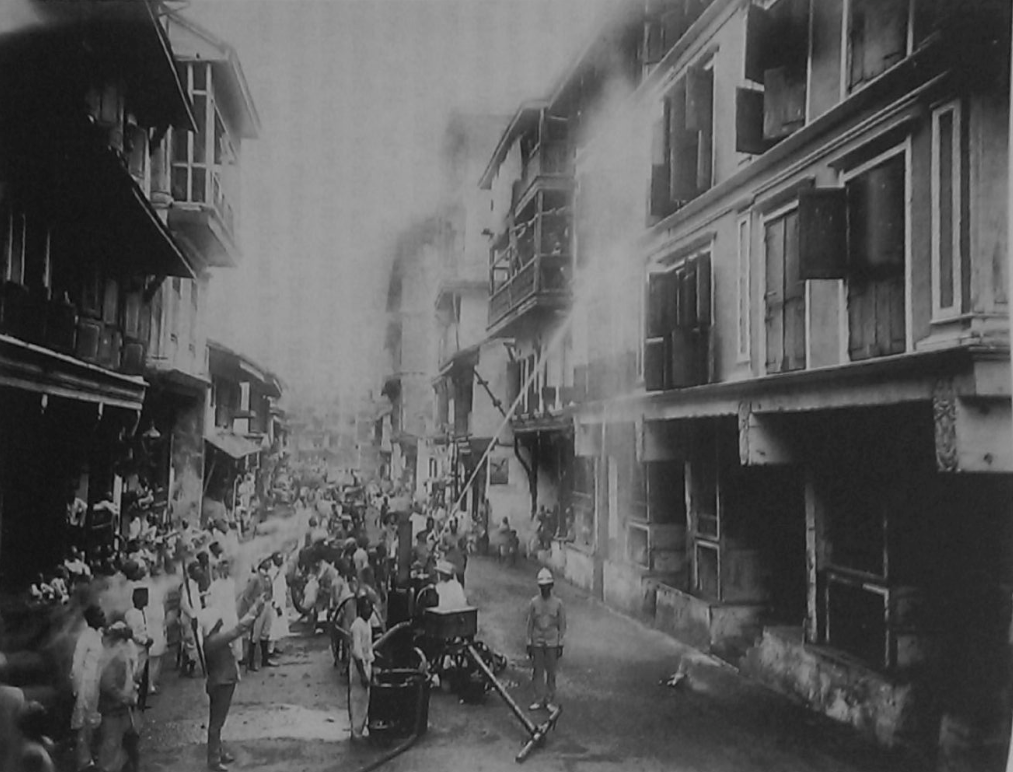

“Dr Viegas’s dispensary was located in Mandvi in the Port Trust Estate. It was a poor neighborhood of narrow and overcrowded streets, with buildings piled atop each other and filth accumulating in its sewers. The drains were silted and blocked up with buckets of night soil that were routinely emptied into the nearby gullies. The night soil found its way into the blocked drains, along with urine and sewage from the privies and sullage water. The worried doctor raised his concerns about these conditions at the Municipal Corporation meetings. Then, at noon on September 18, 1896, he was asked to see a patient, Lukmibai. He learned that she had not slept for three days. She was comatose and yet could be roused easily. Her eyes were bloodshot, and she had a glandular swelling the size of an orange in her femoral region. Her temperature was 104.2 with a pulse rate of 140. There was nothing to explain the femoral bubo. He prescribed diaphoretics, salicylate of soda, and quinine, but her condition worsened in the evening. When he went to see her the next day, she was dead. Surprised by the rapidity of her death, he suspected that this might be a case of Bubonic Plague,” writes noted historian Gyan Prakash.

After seeing another patient showing similar symptoms, and reports of 50-60 such deaths, he was convinced of his diagnosis. By the end of 1896, reports from the time estimate that at least 1,900 people died per week. Many naturally fled the city and the city’s population had dropped from 820,000 in the 1891 Census to 780,000 according to the 1901 Census.

“The administration was baffled by the swiftness with which the [highly contagious] disease spread could not cope. Dr Viegas researched and identified the disease as bubonic plague, and worked tirelessly to fight the epidemic. Identifying rats as carriers, [he] helped combat the spread as well,” says Dr Fleur D’souza, former head of department of history at St Xavier’s College, speaking to Mid-Day earlier this year.

To confirm Dr Viegas’ findings, the local administration enlisted four teams of independent experts. “Official investigations reported armies of rats infected with the disease moving from area to area, spreading the epidemic,” adds Prakash.

Once his diagnosis was proven correct, the Governor of Bombay invited WM Haffkine, the Jewish-Russian bacteriologist who had developed the anti-cholera vaccine, to develop a vaccine for the Bubonic Plague. The challenge before him was rather daunting.

Working three months non-stop at a makeshift laboratory, he soon developed a vaccine ready for human trials. In fact, he reportedly tested the vaccine on himself.

“On the 10 January 1897, Dr. Haffkine caused himself to be inoculated with 10 cc of a similar preparation, thus proving in his own person the harmlessness of the fluid. A form useful enough for human trials was ready by January 1897, and tested on volunteers at the Byculla jail the next month. Use of the vaccine in the field started immediately,” says this profile on the Haffkine Institute.

While 7 members of the control group in the Byculla Jail died, the vaccine reduced the risk of death by upto 50 per cent, although it had some nasty side effects. Armed with Haffkine’s vaccine, Viegas personally inoculated nearly 18,000 residents.

Besides discovering the plague and inoculating patients, he also launched an intense and widespread campaign to clean up the slums and exterminate the rats responsible for carrying the plague. However, the campaign to eradicate the plague also witnessed severe misery and deprivation of the poor. Hundreds of slum dwellings were destroyed by the municipal authorities, while other measures included strict segregation of suspected plague cases, large scale evacuation of people, ban on all mass gatherings like fairs and close examination of people entering the city through rail and ship.

Sadly, mistakes were also made in terms of letting some of the victims slip through the cracks and thus spread the disease to other parts of the country.

“Plague ravaged India seriously for two decades and sporadically thereafter from its outbreak in Bombay city in August 1896, took at least twelve million lives and probably many more, ran up terrible death rates of over 100 per thousands in a season in some towns, created panic and flight, and brought great cities like Bombay and whole provinces, like the hard-hit Punjab, within compass of social disorganization and collapse,” writes scholar Ira Kelin in a journal article titled ‘Plague, Policy and Popular Unrest in British India’.

Nonetheless, Dr Viegas continued to make efforts towards improving living conditions in the city, particularly for the poor. In 1906, he was elected President of the Bombay Municipal Corporation.

“During his long career as an elected city father, Dr Viegas served as a watchdog of the city’s interests in matters of sanitation and public health in particular, making untiring efforts to secure drainage for north Bombay,” writes Clement Vaz.

Meanwhile, he also advocated for the reduction in public transport fares, electricity costs, midwife services free of cost to the poor, and finally free and compulsory primary education.

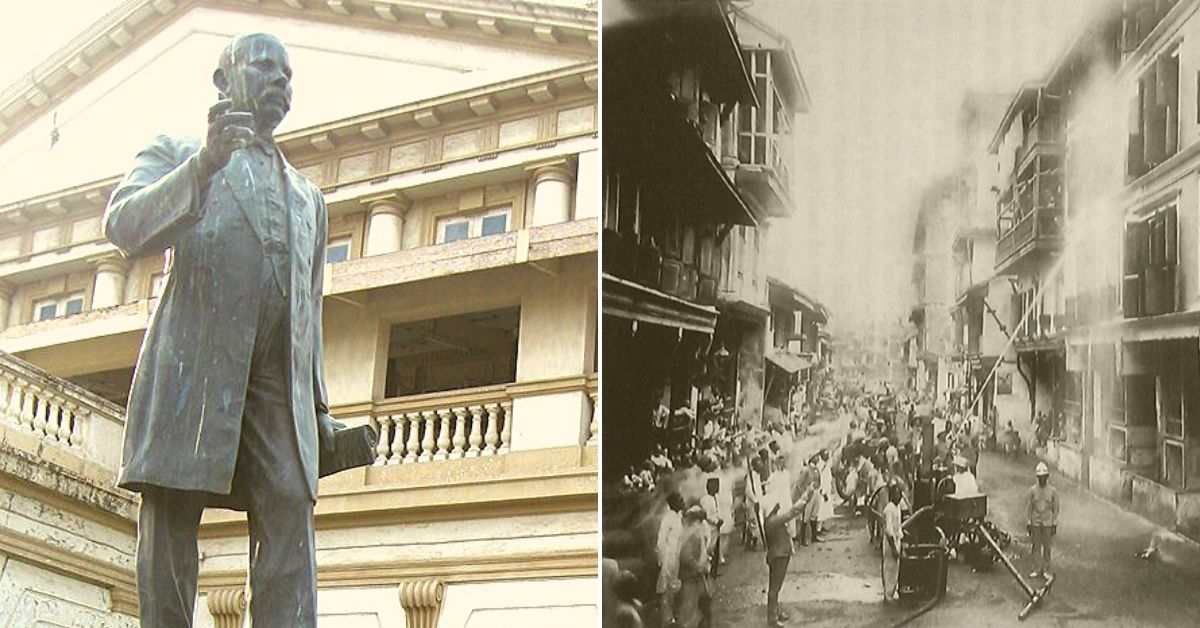

After an incredible life of public service, he passed away on 21 February, 1933. Mumbai still remembers this remarkable public servant thanks to a life-size statue of him that was erected in the Cowasji Jehangir Hall opposite what is today Metro INOX Cinemas.

With his tremendous will power, courage and perseverance, Dr Viegas helped the city of Mumbai tide through one of its most difficult moments in history. For his invaluable service and thousands of other doctors, nurses and health workers who are currently risking their own lives to save others, it’s imperative we remember such stories.

Also Read: Refused a Nobel, This Unsung Indian Scientist’s Research Saved Millions of Lives

(Edited by Saiqua Sultan)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167