This Scientist’s Research Could Stop Millions of Dyslexic Kids From Dropping Out

Until three years ago, 12-year-old Karan would be continuously scolded by his parents and teachers for his inability to read and write in English. Today, he happily attends his school, and can read and write, thanks to Dr Nandini's research!

A neurobiological condition inhibits the development of efficient circuits for reading in children. But in the field, only tests in English were used to diagnose dyslexia says, Dr Nandini Chatterjee Singh, a cognitive neuroscientist with the National Brain Research Centre (NBRC), who has done more for dyslexic children in India than one could ever fathom.

“So, what happens to a dyslexic child in rural Karnataka or Maharashtra? Don’t they get diagnosed with this biological condition?” she asks. We tend to assume that a potentially dyslexic child in these parts is either unwilling to learn or is receiving poor instruction instead of teachers trying to understand their condition.

Worldwide, the incidence of dyslexia is between 10 and 15 per cent. So, in a class of 100 students, 15 may have dyslexia and teachers would be none the wiser.

It is to address this particular problem that Dr Chatterjee established the first cognitive and neuroimaging laboratory in India. Also, her work resulted in the development of DALI (Dyslexia Assessment for Languages of India)—“the first assessment which contains standardised tools to screen and assess dyslexia in multiple Indian languages.”

“Are they not reading well in English because they don’t speak English well or are they not being taught well? If they aren’t reading well in Hindi, are they not reading well in English too? We needed to find answers to these questions,” says Dr Chatterjee.

Dr Nandini Chatterjee

After finishing both her Masters and PhD in Physics, Dr Chatterjee became a postdoctoral fellow at Ohio University, USA, studying nonlinear systems in the late 1990s.

Running out of inspiration, she eventually broke away from pure Physics in 2001, and accepted an offer from a lab at UC Berkeley in the United States. Here, she modelled different biological systems based on nonlinear signals like heartbeats, signals from the brain, etc. A chance meeting with Indian neuroscientist Vijayalakshmi Ravindranath at an annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience changed her life forever.

Ravindranath was in the process of staffing the then newly-established NBRC and invited Dr Chatterjee to join them.

By late 2002, she came back to India and joined the NBRC.

Addressing Dyslexia

“Dyslexia is a learning disorder that involves difficulty reading due to problems identifying speech sounds and learning how they relate to letters and words (decoding). Also called reading disability, dyslexia affects areas of the brain that process language,” says Mayo Clinic.

“We use a combination of functional and behavioural neuroimaging to understand how the brain forms reading circuits, especially among children with dyslexia. When I began this work, I realised that there were some unique things about the way we learn to read,” says Dr Chatterjee, in a conversation with The Better India (TBI).

In most parts of the world, children learn how to read one writing system. But in large parts of South Asia, children are required to learn English too, since it’s a global link language. In India, children learn to read not just one but multiple writing systems (native tongue and English).

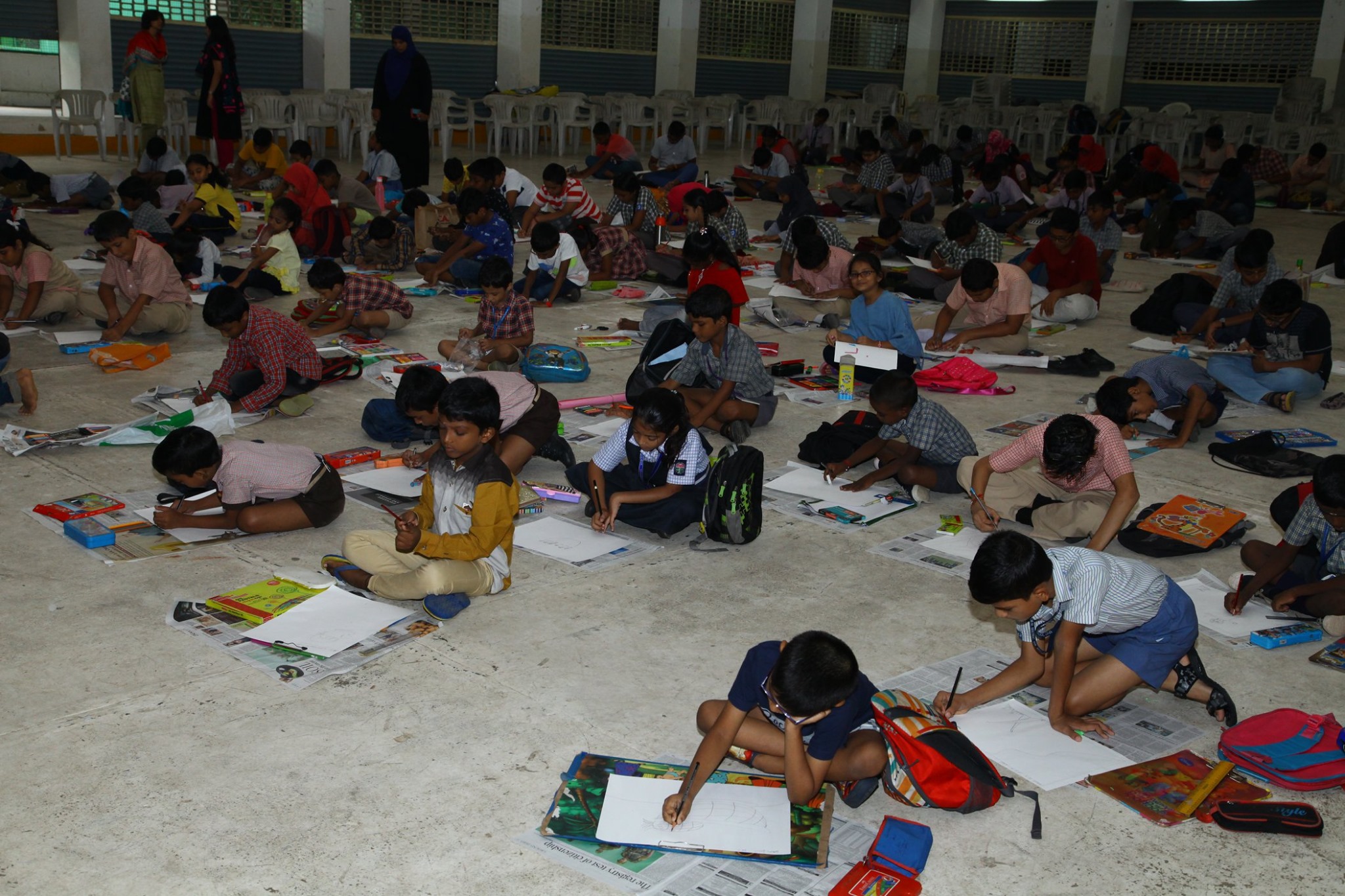

Before creating DALI in 2015, Dr Chatterjee conducted a series of experiments on school children in the Delhi-NCR region to ascertain their reading capabilities.

“We wanted to see how kids are learning to read more than one writing system. In this case, we wanted to learn how kids read in the native language (Hindi, Gujarati, Bengali, etc.) and English. While doing this research, I was looking for standard stimuli which I could use for my experiments. What do I expect of a six-year-old children’s ability to read in school? The textbook is no indicator at all. Class I children cannot read entire textbooks. I made a list of such words, ran them by the teachers, and came up with a list that we found children could read across different classes,” she says.

What they found was that every child doing well in school while getting instructed in Hindi and English was reading well in both languages. Whoever reads well in the native language (Hindi) also reads well in the second language (English).

“We found that some children were not reading at par with others in the class in both languages. Teachers in class didn’t know about this deficit among some of their students. What were these kids lacking? See, reading is built on spoken language. We learn to map sound to letter, not letter to sound because we first learn how to speak. Spoken words are composed of different sounds that have come together. These different sounds are mapped to symbols,” she explains.

Unlike speaking, the brain is not wired to read. But we do have a region in the brain known as Broca’s area (associated with speech production and articulation) which is meant for language. You have to develop a reading circuit in the brain and require outside assistance (a teacher).

DALI

“I then decided to do something for at-risk dyslexic students, particularly in smaller cities and rural areas. Even for children in urban centres, an assessment of dyslexia needs to include the native language, and that’s why we came up with DALI for school teachers and psychologists. Currently, we have built tools for dyslexia screening in Hindi, Marathi, Kannada and English. But I want to emphasise here that as we move from Hindi to English to Marathi and Kannada, this is not a translation. For each language, we have developed the relevant stimuli, besides culture and age-appropriate screening tools. Now, we are building tools for Tamil, Telugu and Bengali,” she says.

Similar tools need to be built for other learning disabilities like dysgraphia (difficulty in writing) and dyscalculia (difficulty in learning maths) as well. Moreover, Dr Chatterjee wants teachers who employ DALI to first get familiar with the child for at least three to four months before screening them for dyslexia. The objective here isn’t to label a child, but pay closer attention and identify areas of learning deficits that need urgent redressal.

However, developing and testing DALI extended beyond Delhi-NCR, and took nearly two years. Dr Chatterjee’s team validated this tool across 5,000 children in 5 cities and 4 languages. At present, DALI is being utilised for children between classes 1-5. Her team is now in the process of extending it to Class 12 as well, which will require developing new stimulus for these students, validating it across different schools and embarking on the process of standardising it.

“We want as much representation from the rest of India as possible,” she adds.

DALI-Reception

Delhi government schools have actively adopted DALI. They’ve been using it for the last two years for children with reading disabilities. Dr Chatterjee has also set up a non-profit called the Nerd Tools Foundation to disseminate DALI on a larger scale. The non-profit conducts teacher training workshops for school teachers, helping them screen children with dyslexia. They also train psychologists on how to use DALI.

Take the example of 12-year-old Karan Singh (name changed) from Delhi, who, until three years ago, constantly faced a barrage of scolding from his parents and teachers for his inability to read in English. Diagnosed with dyslexia thanks to DALI, today, Karan receives additional help from tutors. These days, he happily attends school and has a much better grasp of his language skills.

“We are trying to take this tool to rural India, where there is no understanding of dyslexia. Children often give up and drop out of school. The brain has an amazing ability called neuroplasticity, which is the ability to form new neural connections. This ability allows children to read and train the brain to contemplate. Some kids need more one on one instruction and take a longer time to learn something. Teachers have to develop as many ways to teach dyslexic students,” she says.

Many of these children, for example, learn very well with computer games. Dr Chatterjee is in the process of building a slew of computer games in Indian languages which offer necessary reading skills. The idea is to transfer them onto phones and tablets for these children.

“Instead of imposing a two-language or three language formula on potentially dyslexic children, let’s teach them the process of reading. Once you learn the process, you can transfer it to learning other languages too. The process of learning how to read is the same across all languages. Instead of teaching complex scripts, it would be advisable to develop visual-spatial skills. Parents and teachers must understand this,” she says.

Are languages taught right in Indian schools?

The issues surrounding dyslexia in children extends to a larger question of how children learn languages in India. There is a real problem in how they’re being taught and the way language textbooks are structured. Over the past 25-30 years, we have developed a much better understanding of how learning language and reading happens.

But problems exist. The whole obsession with having children study in English-medium schools is problematic. Before they even understand and speak the language, they have to learn to read, besides the fact that English isn’t the language they communicate in at home.

“The first years must be focussed on understanding the language and speaking it. Then we can go onto reading. The fact that we expect our children to learn to read in Hindi and English fluently by the age of six is ridiculous. Maybe, by the age of eight or nine, it would make more sense. The way we stagger learning and the process needs to change. We must also understand that different languages are structured differently, and so textbooks must be appropriately designed. Until children don’t achieve basic reading skills, don’t promote them to the next class because learning becomes more demotivating. Take the example of Class 8 or 9 students, who barely know how to read. Their confidence drops,” she says.

With the emphasis on learning how to speak first before reading a language, it makes infinitely more sense for children to learn how to read in their native tongue. At home, that’s the language you learn whether it’s Hindi, Tamil, Bengali or Marathi.

Also Read: Delhi Engineer Helps 6000+ Uneducated Moms Become Teachers to Their Kids!

Speaking to The Life of Science, Dr Nandini says, “The child should be first applying this process of mapping sounds (reading) in the language he/she speaks. Then we can transfer the skill of reading to a second language. If for some crazy reason you are insistent that the child has to learn it first in English then first teach the child to speak English then teach him/her to read English. That’s my primary point.”

Dr Chaterjee is currently on deputation to UNESCO’s Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Education for Peace and Sustainable Development (MGIEP) in New Delhi. MGIEP is UNESCO’s first Category One institute in the Asia Pacific region. It is focused on education for peace. She is leading a team to create curricula that would build social and emotional skills in children. Research has shown that such skills can be taught in the classroom. These skills are fundamental to cope with stress, anxiety and to develop resilience in children.

Autism

Before her in-depth research in dyslexia, Dr Chaterjee carefully studied autism. With her study at the NBRC, she wanted to find ways in which autism could be detected earlier.

“Children with autism were sensitive to changes in voice pitch. That can be useful in trying to get them to learn a language. At an introductory level, we found differences in speech motor patterns and posited the idea of whether we can use that as an early screening mechanism of autism. In the early years, the brain is more amenable to interventions, and thus if we found these atypical patterns sooner, we could initiate very early interventions,” she recalls.

Dr Chatterjee hopes to get back to her research into autism soon. Meanwhile, she has one piece of sound advice for parents children with dyslexia or autism.

“The constant need to compare your child with everyone else is pointless. For children to grow and learn good language skills, parents must constantly engage in conversations with them. Isolation for children watching television or the phone doesn’t aid learning. Social interaction between children and parents must be extensive. Talk to your child any chance you get,” she says.

(Edited by Saiqua Sultan)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167