How 3 Indian Doctors Pioneered the Use of ORS to Treat Diarrhoea & Saved Millions!

Way back in 1953, Hemendra Nath Chatterjee first treated 186 patients with an “oral glucose-sodium electrolyte solution”. But it’s widely believed that “racism or the lack of a ‘scientific’ rationale prevented the widespread adoption of his work.” #IndiansInScience #LostTales

Nine times out of ten, your friends and family would reach for a packet of ORS in their homes just in case their bowels begin acting up, because anyone with a cursory understanding of basic medicine knows that a glass of Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) can help replace the fluids your body has lost during a bout of diarrhoea like nothing else can.

Quit spending money on regular sanitary pads that are made of plastic, and cause rashes and redness. Instead, switch to these economical and eco-friendly menstrual cups made from 100% medical grade silicone.

Nonetheless, what we do not commonly understand is the date and circumstances behind the “discovery” of ORS.

Despite the long and devastating history of diarrhoea and cholera, it was only by the 1980s when the global medical community came to a broad consensus around the prescription of ‘oral rehydration therapy’ (ORT) to tackle these diseases.

Prior to the introduction of ORS, “the reigning cholera treatment paradigm” comprised of the “gradual intravenous administration of electrolyte solutions, blood transfusions, fasting and then the gradual resumption of feeding at the end of a ‘starving’ period,” writes James Webb Jr in his book ‘The Guts of the Matter: A Global History of Human Waste and Infectious Intestinal Disease.’

Nonetheless, it was Hemendra Nath Chatterjee, a Bengali doctor, who first rehydrated his patients with “mild to moderately severe cholera … without intravenous or parenteral transfusions.”

According to this paper, he “treated 186 patients with an oral glucose-sodium electrolyte solution” in 1953.

This solution would closely resemble the one Dr Davin Nalin and Dr Richard Cash, considered by many in the West as early pioneers of oral rehydration therapy, used 15 years later although it was tested under the aegis of the Johns Hopkins University International Center for Medical Research and Training (ICMRT) in Calcutta in the refugee camps during the Liberation War of Bangladesh in 1971. Chatterjee managed to publish his findings in The Lancet, a prestigious global medical journal.

“However, Chatterjee’s work failed to provide controls and net fluid balance sheets, scientific tools that might have fostered credibility; and his use of exotic Indian plants to halt vomiting and diarrhoea, as well as his administration of some rehydration therapy by enema, may have struck the readership of the Lancet as being too foreign and unscientific. Whatever the case, his article failed to stimulate follow-up studies. It is generally agreed that racism or the lack of a ‘scientific’ rationale prevented the widespread adoption of his work,” says Joshua Nalibow Ruxin in a paper published in Medical History, a peer-reviewed international medical journal.

Following Chatterjee’s findings, Qais Al-Awqati, an Iraqi physician, used ORT in 1966 to combat an outbreak of cholera in Baghdad. Alongside two other doctors, his work was also published in The Lancet.

Both Al-Awqati and Chatterjee’s findings ran contrary to the reigning cholera treatment paradigm at the time.

Strengthening the claim of ORT

Besides Dr Nalin, Dr Cash, and other Western researchers, two Indian doctors played a pivotal role in establishing the effectiveness of ORT.

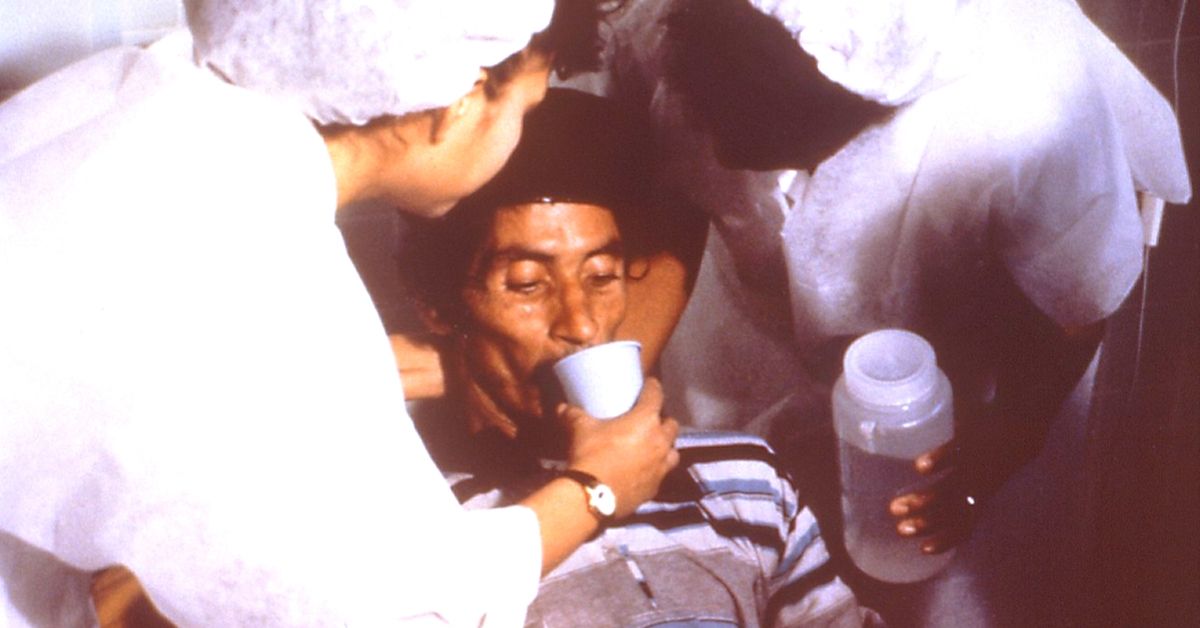

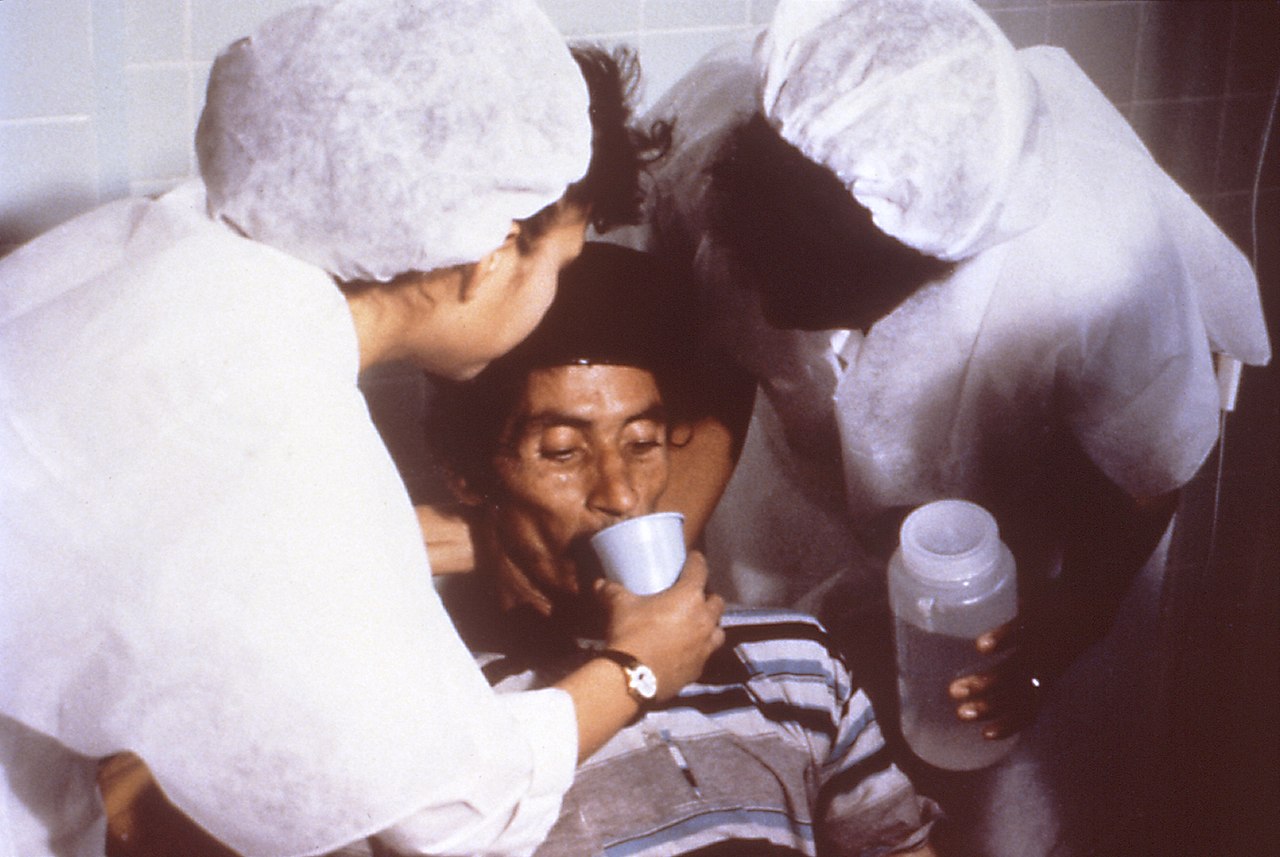

Dr Dilip Mahalanabis, who was also studying cholera and other diarrhoeal diseases at a hospital in Kolkata, conducted a remarkable series of treatments in 1971 at a refugee camp in Bangaon.

These treatments played an instrumental role in proving that doctors aren’t needed to administer ORS solution to other patients.

Another influential Indian here was Dr Dhiman Barua, who was a mentor to Mahalanabis and also pushed for ORT in Africa the year before, where 40 countries were affected by cholera.

“When the cholera epidemic began in 1971, we had to leave our research and go out into the field to work with the refugees. The government was unprepared for the large numbers. There were many deaths from cholera, many horror stories…Within 48 hours of arriving there, I realized we were losing the battle because there was not enough IV and only two members of my team were trained to give IV fluids,” says Dr Mahalanabis, speaking to the WHO about his initial experience in Bangaon.

Running out of IV saline and without the facility of consulting other domain experts at the time, he went ahead with administering ORS more in hope.

“Within two or three weeks, we realized that it was working and that it seemed to be all right in the hands of untrained people. However, people did need some supervision and persuasion that it really would work. People knew that IV saline was the treatment for cholera because cholera is endemic in the region. At that time, we coined the term ‘oral saline’. We told them that this was also saline, but that it was given by the mouth…We prepared pamphlets describing how to mix salt and glucose and distributed them along the border. The information was also broadcast on a clandestine Bangladeshi radio station,” he adds.

In Africa, a year earlier, Dr Barua came across similar constraints.

“In those days IV saline was made in glass bottles, as there were no plastic bottles, and a one-litre bottle was so heavy that to transport it by air was many times more expensive than the fluid itself. This made it impossible to provide, for example, tonnes of IV saline that were needed to meet demand in Africa, where 40 countries were affected by cholera in 1970,” he tells WHO, in a separate interview.

The success of ORS under these extremely trying circumstances came as a major source of validation for Dr Barua as well.

“Mahalanabis kept drums of oral rehydration fluid each with a nozzle on the side and told relatives to fetch the solution in cups and mugs to feed the patients. When the patient is thirsty, he drinks. When he’s no longer thirsty, he’s no longer seriously dehydrated. When the patient is healthy again, the solution tastes bad. When you are very dehydrated, the taste of ORS is wonderful. What I saw in Bangaon convinced me that our decision to use ORS solution in Africa and allow minimally trained people to administer it, had been right,” says Dr Barua.

The history of medicine is replete with stories of medical practitioners across different corners of the world, finding solutions for diseases that have ravaged humanity.

For ORS, the story is no different, but billions around the world have felt its impact. Thanks to the pioneering work of various medical practitioners, particularly three Indians, millions of lives were saved and are continuing to be saved even today.

Also Read: Refused a Nobel, This Unsung Indian Scientist’s Research Saved Millions of Lives

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

Similar Story

Netaji Bose’s Favourite Eatery Has Been Serving Traditional Delicacies for Over 100 Years

The Swadhin Bharat Hindu Hotel in Kolkata, started by Mangobindo Panda, is a century-old pice hotel where Indian freedom fighters like Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose would enjoy Bengali delicacies.

Read more >

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167