Engineering Dropout to Organic Farmer Growing 300+ Native Veggies: TN Man’s Inspiring Story!

Apart from growing chemical-free food, he also created a seed bank named Aadhiyagai (which means first blooming in Tamil), with more than 300 native vegetable and fruit seeds.

In the village of Kuttiyagoundanpudur, close to the arid region of Oddanchatram in Tamil Nadu’s Dindigul district, lies Aadhiyagai Parameswaran’s six-acre farm.

Want to grow your own food? Here are some seeds to help you take the first step.

The area lacks a perennial source of water to keep crops well-fed, but 29-year-old aeronautical engineer-turned-farmer, Parameswaran is confident his farm will thrive. His crops can withstand severe drought conditions because they are native to this arid region.

Born in a family of farmers, he grew up watching his parents toil on leased dryland. Although he was studying engineering, his love for the soil surpassed his will to graduate.

“Undoubtedly, a combination of genes, environment, and passion made me discontinue engineering in my fourth year to become a full-time organic farmer in my village.”

The family was upset at his decision. His parents asked why their son would want to quit the chance at a comfortable life to toil in the soil.

“They were disappointed in the beginning, as any other parent would be. But now, looking back at my journey, they are happy and proud of my decision. Apart from them, my wife Kayal has been a strong pillar of support in my farming journey.”

In 2014, he took to organic farming on a leased six-acre plot. He was inspired by G Nammalvar, green crusader, agricultural scientist, environmental activist, and organic farming expert. He had attended a workshop at Vanagam in Karur, where he learnt some ideals of the expert. Coincidentally, BT brinjal was making headlines at the time.

To kickstart his seed-saving journey, the young farmer travelled across villages in Tamil Nadu, interacting with experts and veteran farmers to document native vegetable varieties. These travails were an eye-opener.

Apart from growing chemical-free food, he also created a seed bank named Aadhiyagai (which means first blooming in Tamil), with more than 300 native vegetable and fruit seeds. Collected and documented over the past five years, he now distributes them to farmers in the neighbourhood and youngsters in cities and towns.

“I was surprised to know the names of more than 500 varieties of brinjal in Tamil Nadu. Likewise, there are as many varieties of okra/lady’s finger, which can give yields for as long as three years. We even have the rarest pink-coloured lady’s finger in the Kongu belt.”

Unfortunately, many of these varieties had dwindled into extinction because of lack of cultivation and multiplication. This furthered his resolve to conserve them.

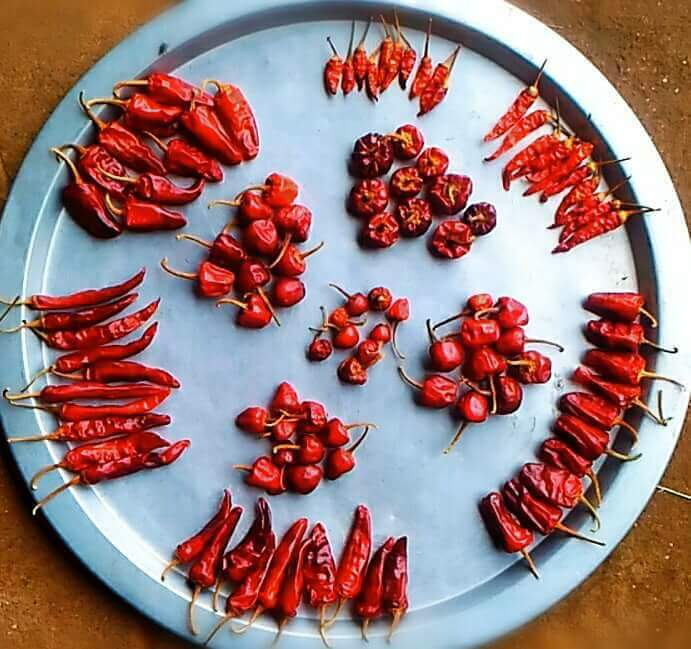

Presently, his seed bank has 13 varieties of okra/lady’s finger, 30 varieties of Brinjal, 30 varieties of bottle gourd, ten varieties of indigenous maize, rare varieties of vegetables like clove beans, winged beans, and sword beans.

Many varieties he collected were bring grown by farmers in their backyard for consumption and not commercial use, while others were sourced from seed savers and festivals from across the country.

He encourages local farmers to sow these native varieties in small patches of land for home consumption and multiplication.

Giving us a sneak peek into the workings of this farm, Parameswaran reveals that three acres out of the six-acre land are used to cultivate groundnuts. The remaining three acres are used to cultivate indigenous varieties of tomatoes, chillies, winged beans, clove beans, sword beans, ladies finger, bottle gourd, snake gourd and brinjal.

Growing native varieties does not require additional external input, so he doesn’t use manure.

“Our land comes under a dryland region. Native seeds are naturally potent, drought-resistant, and have higher immunity against pests and diseases. Manure is not required for them either. An occasional drizzle is enough to sustain them for a good yield.”

How then does he control pests?

“Instead of monocropping, we follow multi-cropping, so that there is a minimal chance of crops being affected by pests. This eliminates the need for pest control. The idea is to invest in diverse crops, indigenous to various regions.”

Apart from farming, another source of income is helping people set up terrace gardens and backyard farms. He has conducted gardening workshops in more than 200 locations.

“Even in congested cities like Chennai and Madurai, we help people set up green spaces. Our workshops are mostly experiential and focused on helping people set up backyard farms or terrace gardens. We given them seeds from our seed bank and once they use them, we collect some seeds from them to replenish our repository. It is a win-win situation all around!”

Why is conserving native varieties so crucial?

He answers, “Since the dawn of hybrid varieties, local farmers are left without seeds because they can’t afford them. An average farmer spends 20 per cent of his income on seeds alone. While the lifespan of hybrid variety okra is only 100-120 days, native varieties are longstanding and can yield from six months to three years. These can help our farmers, and since these seeds are location-specific, there is an urgent need to mobilise the youth to join forces in conserving them.”

Parameswaran emphasises the need for the youth to take up agriculture. He says, “Did you know more than 2,000 farmers give up farming every day? This phenomenon is called the Great Indian Agro Brain-drain. There is an inherent need for us to make our youth aware of the prevailing conditions.”

He suggests that we could begin by teaching them about soil health, rainfall patterns, cropping cultures, and empowering them about the severity of the water crisis and the ancient art of water harvesting.

“Only when we make agriculture a part of our mainstream education, will it be able to bring a little cheer to the farming community,” he concludes.

“My parents didn’t own any land. I grew up watching them practice agriculture for 40 years on leased land in more than 20 locations across Tamil Nadu. My only dream is to own a farm on land I can call my own and set up a seed bank there,” he signs off.

If this story inspired you, get in touch with Parameswaran. Write to him at [email protected], check out his Facebook page or WhatsApp him on 085263 66796.

Also Read: Gurugram Farmer’s Technique Stops Wastage of Veggies, Multiplies Income by 4 Times!

Check out some more pictures here:

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167