What Connects India to Alan Turing, the Genius Who helped Solve Hitler’s ‘Unsolvable’ Enigma?

The man who built the world’s first programmable digital computer, Alan Turing is now celebrated for his code-cracking work that proved vital to the Allies in World War Two. But did you know what links him to Madras and Tungabhadra Bridge? #History

Most might know this math genius as the father of modern computing and artificial intelligence.

Some others might know him for his contribution during World War II by breaking open the Nazi Enigma code system which was considered to be virtually ‘unsolvable.’ This feat was one of the few contributing factors to the victory of the Allied powers against Adolf Hitler.

A legend, many even remember him in sorrow—a brilliant man shrouded in a tragic tale of persecution and social ostracisation for his sexuality.

From the point where I started to type this story to the point you read, it is all an incarnation of the genius machine created by Alan Turing.

And yet, despite the vast breadth of information now floating about him, we barely know about his past that finds a direct connection to India.

Yes, you read that right.

Turing’s Indian Connect

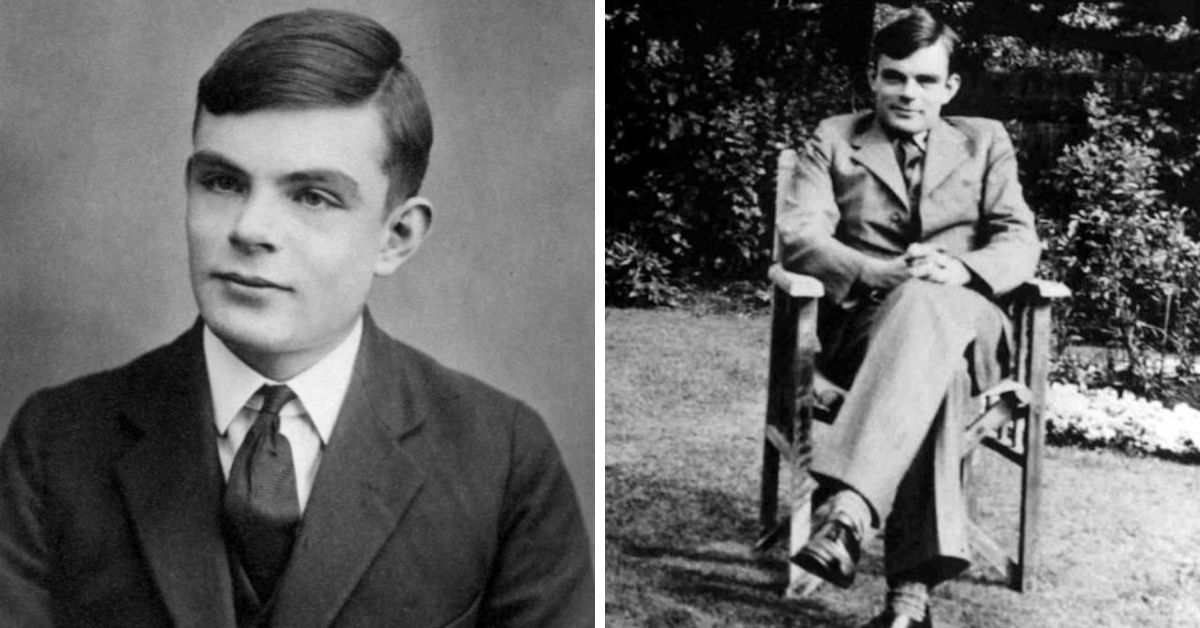

Like many prominent individuals of the time, Alan was born to parents who spent a large chunk of their lives working in colonial India, in 1912. His father, Julius Turing was an Indian Civil Service (ICS) officer posted in Chatrapur, a town under the Madras Presidency, and now, in present-day Odisha.

Fluent in Tamil and Telugu, the British ICS officer had worked in various remote areas like Anantpur, Srikakulam and Kurnool, and was finally promoted as the secretary in-charge of Agriculture and Commerce in 1921.

However, Julius was not the only or the first Turing to reach the Indian shores. Instead, before him, since the 1700s, many Turings have lived in India, especially Major John Turing, who fought the Siege of Srirangapatna (1792).

Even his mother, Sarah Turing (Stoney) was born in Podanur, Tamil Nadu and was the daughter of Edward Waller Stoney, the Chief Engineer of the Madras and South Mahratta Railway,

Stoney was the man behind the Tungabhadra Bridge and the ‘Stoney’s Patent Silent Punkah-wheel,’ an ingenious non-creaking punkah or fan designed to ensure better sleep.

Interestingly, she grew up in a house in Coonoor, which is now owned and occupied by Nandan Nilekani, co-founder of the Silicon Valley giant, Infosys.

It was Julius’ work that brought the family to colonial India, where his grandfather had served as the general in the Bengal Army.

Despite this prominent Indian background, Alan hardly lived in India.

Although many biographers argue that he was born in India, most settle that he was born in Maida Vale, London. They believe that his mother Sarah had travelled back to England to deliver him to avoid any social stigma against the ‘country-born.’

As per the plan, Sarah was to bring her son back to India after the delivery but had to leave him with guardians in Sussex due to health complications. This way, Alan never really returned to live with his parents in India, and instead, Julius and Sarah would frequently travel between Hastings in the UK and India.

Alan, meanwhile completed his education in premier institutes in the UK (Cambridge) and the USA (Princeton’s Institute of Advanced Study) and was later recruited as one of the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, when the War broke.

When Britain’s pride lost amid prejudice

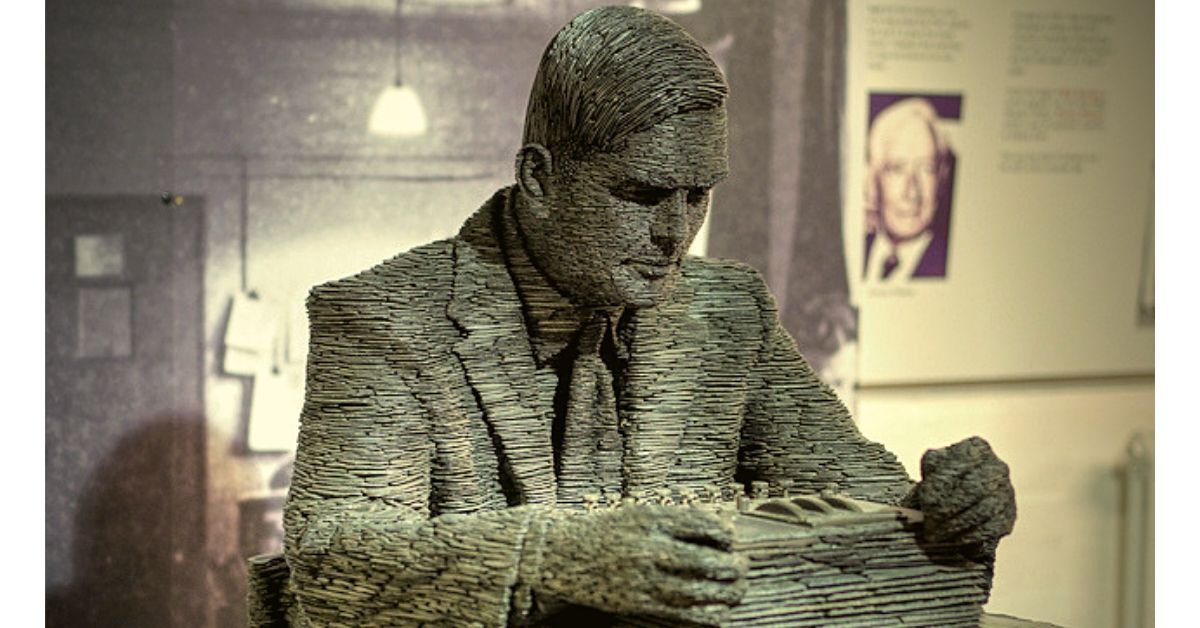

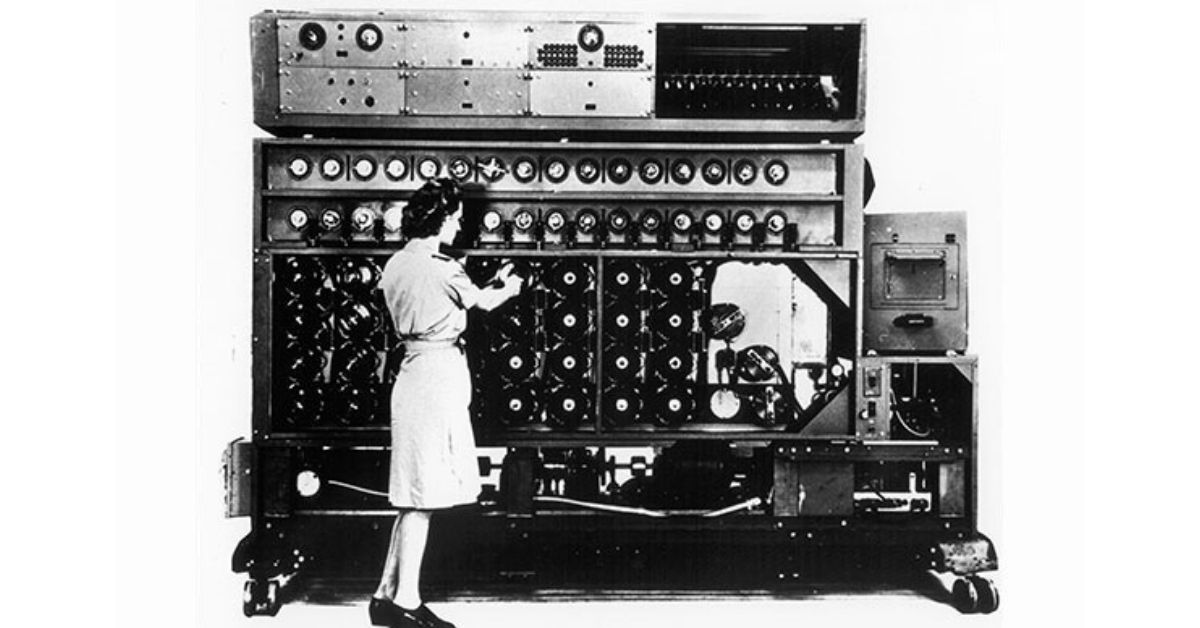

Alan rose to fame due to his groundbreaking work in ushering modern-day computer science. His paper, ‘On Computable Numbers’ published at the age of 24, in 1936 led to the Colossus computer which was created to break the Enigma code.

Even after the War, Turing continued to work on developing some of the world’s first functioning computers and formed the base for the concept of artificial intelligence. Remnants of his work continue to echo in modern technology from computers to smart devices.

However, despite being the pride of Britain, he was subjected to barbaric treatment by the British government as he was a homosexual, which was an offence at the time. He was arrested in 1952 on the grounds of ‘gross indecency’ and was given two choices as a penalty—imprisonment or chemical castration. He chose the latter.

Also Read: Erased by History, These ‘Tawaifs’ Were Unsung Heroines of India’s Freedom Struggle

Ostracized from the society, Turing was 42 when he breathed his last. He died from cyanide poisoning. With a half-eaten poisoned apple left by his bedside, some investigators believed it to be a suicide, while others argued that it was much more than that.

“He also knew too much in the sense that he was perceived by the British government in the years after World War II as a security risk because of the quantity of classified information that he had in his possession. And, therefore, he was really hounded by the British police who were concerned that because he was gay, he would—he could be easily blackmailed or seduced into going over to the East,” biographer Davin Leavitt (The Man Who Knew Too Much) says in an interview to NPR.

Turing believes machines think

Turing lies with men

Therefore machines do not think

Yours in distress,

Alan

This syllogism written by Alan in one of his last letters is an immortal remnant of his tumultuous yet interesting past that eventually rolled into an end clouded in mystery.

While biographers and historians continue to sift through it to find the truth, it’s essential that we pause and honour Turing’s life and achievements to remember what a man, what a gift he indeed was to the world!

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167