Calling 108: How One Institution Pioneered Emergency Medical Services in India

Serving nearly 800 million Indians, the 108 service has saved the lives of over 2 million patients since its inception in August 2005. Here’s the story behind this revolutionary initiative!

Since its inception in August 2005, the 108 medical emergency response services has saved the lives of over 2 million patients across 15 states and 2 union territories.

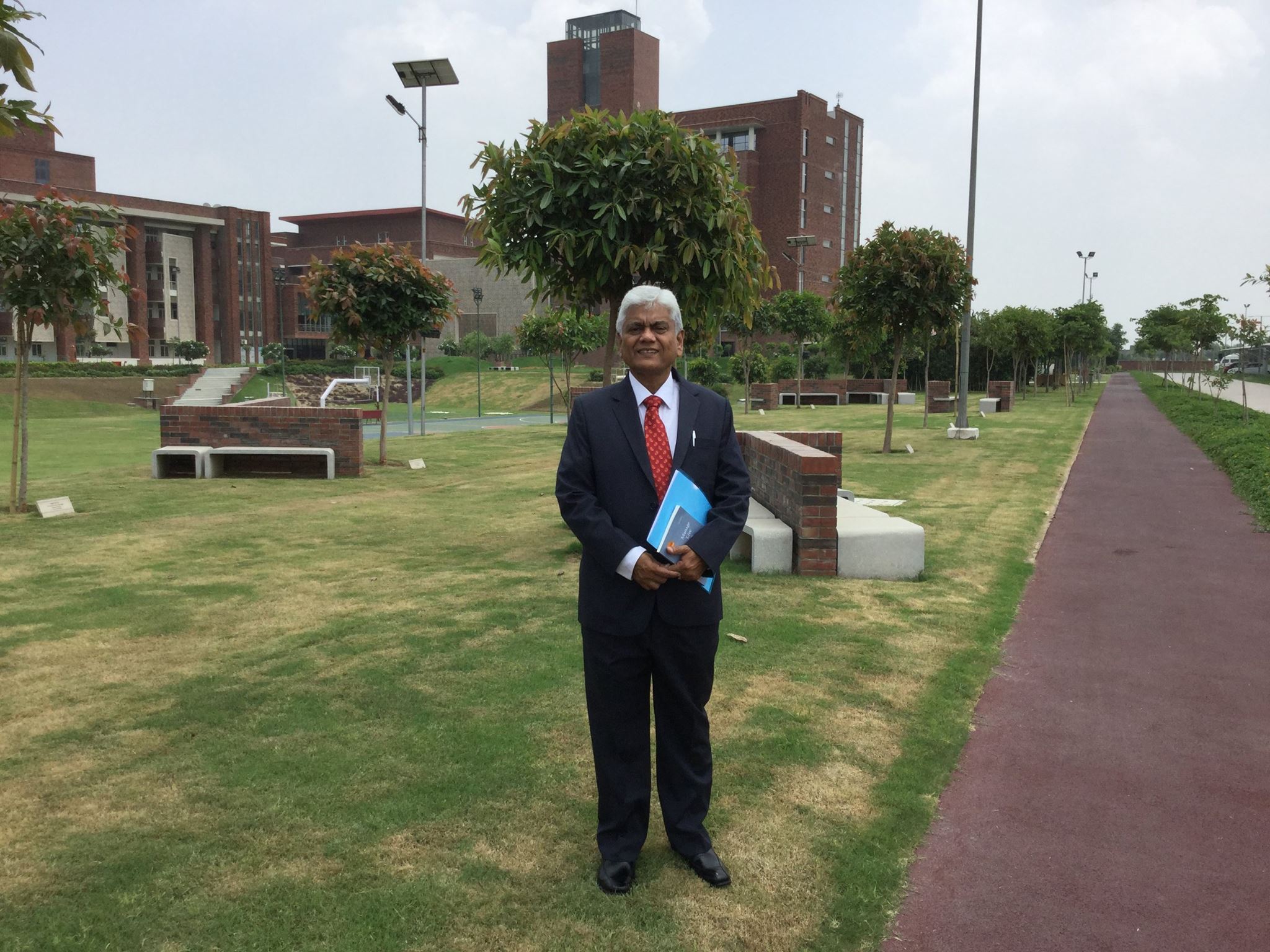

Started by the Emergency Management & Research Institute (EMRI), a non-profit currently under the aegis of Indian conglomerate GVK, the 108 service attends to “80,000 calls daily and touches a population of 800 million,” according to K Krishnam Raju, Director, GVK-EMRI. Besides, it has also instituted a much-needed structural change in how emergency medical care is delivered to India’s poorest patients in urban and rural areas before they are taken to a hospital. EMRI was first an initiative undertaken by Ramalinga Raju, Chairman of Satyam Computer Services.

First conceptualised in (united) Andhra Pradesh by the late Dr AP Ranga Rao, a man of remarkable intellect and passion who possessed a burning desire to do something for the people, a robust medical emergency system was Rao’s primary focus. Spending close to a decade working with the British National Health Service (NHS) learning about emergency systems, his vision was to introduce the same for India’s public health system.

Nonetheless, it was Venkat Changavalli, the first CEO of the Hyderabad-based Emergency Management and Research Institute (EMRI), who was the real architect behind 108. And, for the matter, if it weren’t for his father, Venkat would have never even taken up the job.

“I was the CEO of a German multinational based out of Chennai, when I chaired a conference titled ‘Beyond Creating Value’ in January 2005. The chief guest at the time was Satyam Computer Services chairman Ramalinga Raju. Following the conference, Raju approached me with a proposal of doing something concrete in emergency services. He didn’t have 108 in mind or even a real plan, but wanted to tap into my extensive corporate experience, passion for innovation and a latent desire for public service,” says Venkat, in an exclusive conversation with The Better India.

Initially, he had rejected the proposal, unwilling to give up his high-paying job and wasn’t prepared to get into public service just yet. However, a conversation with his father, a retired school teacher, changed everything. His father spoke of building a legacy, asking Venkat to utilise his time, money, skills and knowledge to help the millions he doesn’t know. Following the conversation, Venkat called up Raju and on 15 April 2005, he took over as CEO of EMRI.

Problem statement

Before the 108 service became operative, researchers at EMRI had estimated that 4 million Indians were dying every year because of inadequate medical emergency services. Of the 4 million deaths, around 60 per cent (2.4 million) were related to cardiac-related emergencies, followed by 1,50,000 pregnancy-related deaths, 1,40,000 road accident fatalities, respiratory distress, snake bites and suicide attempts, among other causes.

“Through its research, EMRI has [also] learned that 10 per cent of Indians face emergencies but either don’t recognise them as such or have nowhere to call,” says this July 2010 Harvard Business Review report.

“Instead of one number people can dial for medical emergencies, there were multiple helpline numbers for government and private hospitals. Moreover, there were no standardised ambulances that offered pre-hospital care. These vehicles were largely transporting ambulances without the requisite equipment or expertise to stabilise a patient. If these facilities were available, patients were charged an exorbitant amount. Government ambulances were there, but in poor working condition. This was the state of affairs,” recalls Venkat.

Evolution of 108

EMRI first signed an agreement with the (united) Andhra Pradesh government on 2 April 2005, stating that the latter would be a non-funding partner while the EMRI, with its own funds would design, deploy and run the ambulances at their own expense.

“Receiving Rs 34 crore from Ramalinga Raju and 17 members of his family, I utilised this corpus of funds to construct the EMRI building, bought hardware for a call centre, purchased its first 30 ambulances and started the emergency service on 15 August 2005,” says Venkat.

First launched in Hyderabad, the 30 ambulances were running in Tirupathi, Vishakapatanam, Vijayawada and Warangal by September end.

Within a few months, however, Raju wanted to expand the sphere of EMRI’s operations. Borrowing Rs 40 crores from a bank, EMRI launched another 40 ambulances. By June 2006, they were operating 70 ambulances in about 50 cities and towns in Andhra Pradesh. They used the first Rs 74 crores to build infrastructure, buy the ambulances, hardware and meet operational expenses.

Although privately funded, the State government was closely overseeing the project. Upon seeing the success of the operation, the State government, in August 2007, decided to fund 95 per cent of the operation. The parties signed a second agreement on the same the following month.

As per the second agreement, the government would fund the purchase, and operation of these ambulances, besides conduct performance reviews. Meanwhile, EMRI would inform them about the cost of ambulance, equipment, how much money was spent each quarter and highlight performance indicators, among others.

“By August 15, 2007, the State government had 700 ambulances running on its 108 service. We were nominated as a single nodal agency to run the 108 ambulance service with total operational freedom,” informs Venkat.

How does it work?

There are three critical facets of the 108 emergency service—Sense, Reach and Care.

“In the United States, for example, there are different agencies that oversee detecting (sense) the emergency, an ambulance reaching the patient on time and caring for them. In India, we decided to integrate these services under one umbrella so that coordination becomes easier unlike the 911 system in the United States. We wanted to adapt it to Indian conditions,” shares Venkat.

There they had 6500 call centres for a 30 crore population for receiving the calls, says Venkat, but we decided to have one centre for each state. For Andhra Pradesh with a population of 9 crore, one centre would receive all the calls, make dispatches, run the fleet ambulances and offer pre-hospital care. We envisioned integrating all these services into one system.

Sense Process

Once you dial 108, the call lands at the Emergency Response Centre, where a communication officer (CO or call taker) receives it. The CO asks for all the relevant details and fills them on the screen to be sent to the dispatch officer (a senior officer with some medical training) in the same building. The dispatch officer takes the call from call taker, validates the information about when the incident happened, locates the nearest available ambulance and relevant hospital, and accordingly transfers this information to the requisite ambulance personnel. This is part of the Sense process.

Reach Process

The Reach process takes off when the ambulance receives information and proceeds to the emergency site. While heading to that site, they get in touch with the caller, who could be the victim, a relative or a friend, and asks them to take some basic precautions like ensuring the patient breathes properly. These suggestions fall under pre-arrival instructions so that if the ambulance take 15 minutes to reach, both the patient, their family and friends remain calm during the whole process. Each ambulance covers a population of about 1,00,000.

Care Process

The care process starts at the site of the incident. These trained ambulance personnel offer immediate relief like stopping the bleeding in the event of injury, splint the patient in the event of a fracture or put the patient on a defibrillator or ventilator in case of a heart attack. They check for clear airways, ensure the patient is breathing and that the blood circulation is maintained.

At the hospital, the ambulance hands over the patient and collects an acknowledgement from them in the form of PCR (Patient Care Record), which contains the patient’s basic details and vitals at the time of transfer to ambulance, during the travel and at the time of handing over. Vitals include body temperature, SpO2 levels, pulse rate, respiratory rate, and other such signs.

Thanks to these ambulance services, an average patient’s vitals have improved at the time of handing over, according to Venkat.

Training of personnel

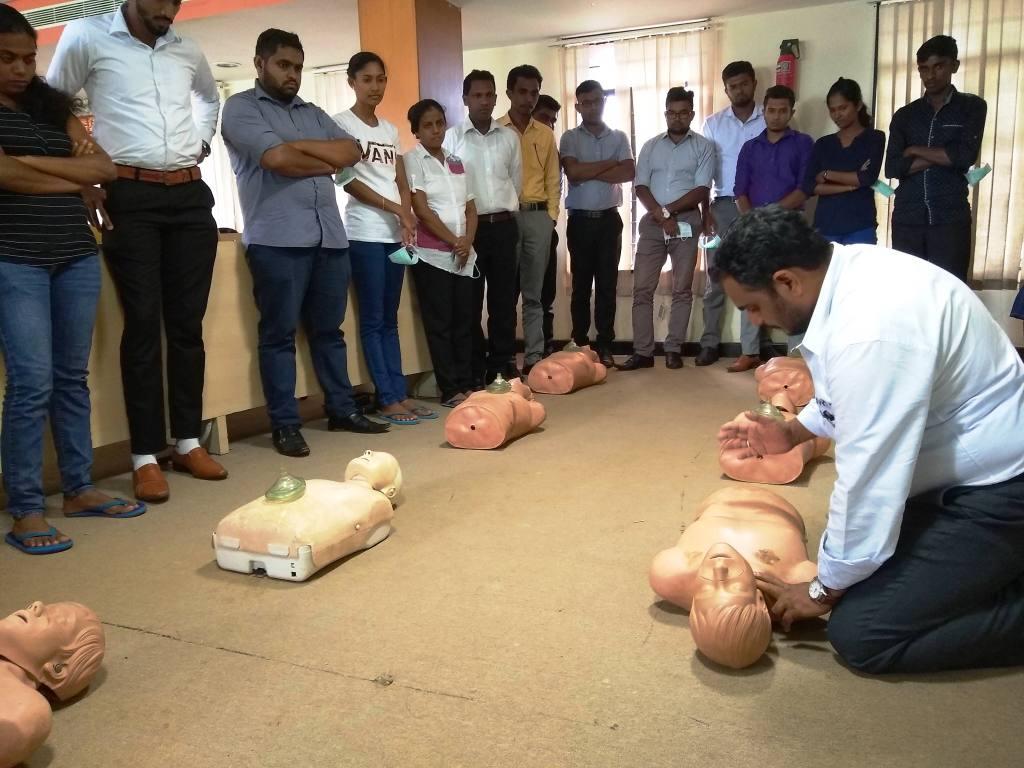

“Earlier, our country did not have trained manpower of first responders for such emergencies. So, I took BSc graduates, and made them undergo a rigorous two-month training programme. For the first month, there were lessons on human anatomy, physiology and pathology. Subsequently, we identified types of emergencies – heart attack, snake bite, suicide attempt, etc. – and what they must do to save the patient under each situation,” says Venkat.

The students practiced on mannequins, rode in the ambulances as trainees and then posted in an ambulance. Six months later, they were brought back for ‘refresher training’.

“Later on, we signed an agreement with the Stanford School of Medicine to provide basic and advanced training for those who can conduct heart and lung-related emergency procedures like intubating the patient,” recalls Venkat.

Researchers at EMRI even went to Stanford, and in collaboration, designed a two-year post-graduate programme on emergency medicine.

A great majority of the students for the course were from rural areas, who became advanced paramedics with a diploma. They studied in this programme at the EMRI, started in September 2007.

Technology

“Technology was not used in an ambulance for pre-hospital care till the emergence of 108 Ambulance service. With Satyam as a technology partner, we were able to set up the call centre. Just before I demitted office on 10 January 2011, we had a GPS system in place to track the nearest ambulance and relevant hospital and an automatic vehicle location tracker system.

By the time Venkat left, EMRI was overseeing 3,200 ambulances across 12 states, including Gujarat and Tamil Nadu covering a population of 430 million.

“Sitting in the head office, we could track in real time which ambulance was carrying what patient, and their vital signs,” says Venkat.

What EMRI did so well is innovate at a time when India did not have a reliable GPS mapping system. Instead, as this Harvard Business Review report states:

“The Emergency Relief Operators route ambulances using dynamic optimisation algorithms based on the nature of the emergency, its severity, and the ambulances’ locations.”

Challenges of running the Behemoth Operation

For Venkat, running EMRI came with its fair share of challenges. The biggest obstacle was running the institution when Ramalinga Raju went to jail on 7 January 2009 on charges of corporate fraud. At the time, Venkat was operating EMRI in eight states.

“For four months, I was running it without a boss and salary. From January to May 2009, there was a real crisis. We received assurances from the then Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister YS Rajasekhara Reddy for funding, and fortunately after four and a half months, GVK was brought in to our rescue,” he recalls.

Outcomes

When Venkat quit, EMRI was handling 12,000 emergencies per day.

“Out of 12,000, our estimate is that 4-5 per cent are those who would have died had the service not existed. In those six years, we saved 5,20,000 lives because of timely emergency medical care, and this included those who survived more than two days after admittance into hospital. We had about 18,000 employees at the time. On an average, a 108 ambulance would reach within 15 minutes in urban areas and 20-25 minutes in rural areas during my time,” informs Venkat.

Today, 108 receives 80,000 calls and responds to 22,000 emergencies per day, besides employing over 47,000 people.

Despite all the gruelling effort, seeing ordinary citizens approach and personally thank him for EMRI’s 108 service is what makes it all worth it.

“Once I was late for my flight, but instead of admonishing me, the flight attendant upon seeing my name on the passenger manifest asked me if I was the CEO of EMRI. When I responded in the affirmative, she went on to tell me how we saved her father’s life. That’s the ultimate validation,” he says.

Conclusions

It’s scale of operation has expanded exponentially, and while some states today have maintained their partnership with EMRI, other private players have entered the game in certain states.

These private players are looking to exploit some of the inefficiencies that have crept in. For example, the response time continues to hover around levels seen in 2011 in some states. The 108 service is still not uniformly available across the country, while in some cities, less than 5 per cent of patients travel in ambulances with life-support facilities. There are also questions surrounding the serviceability of these ambulances as well.

Having said that, EMRI remains a global pioneer in offering emergency care. Doubling up as a research institute, “Its research capabilities are changing the way many countries think about emergency-care management,” says this 2010 Harvard Business Review report.

Also Read: How Indian Cops Are Taking Emergency Help to The Next Level

Building critical emergency systems at a time when there was none has brought us this far. But there is still some way to go.

(Edited Saiqua Sultan)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.