From the African Bushes to Indian Bureaucracy: The Long Journey of the Safari Suit

When a sarkari babu (government officer) or baniya (Marwari businessman) stepped out of his home in a safari suit, the sheen of the outfit accorded him a sense of respectability and sincerity.

In the series ‘Icons of India’ , we take a look at the iconic objects that collectively defined the Indian experience over the past 68 years. From things that brought the world to our living rooms to tasty treats, take a nostalgic journey down memory lane!

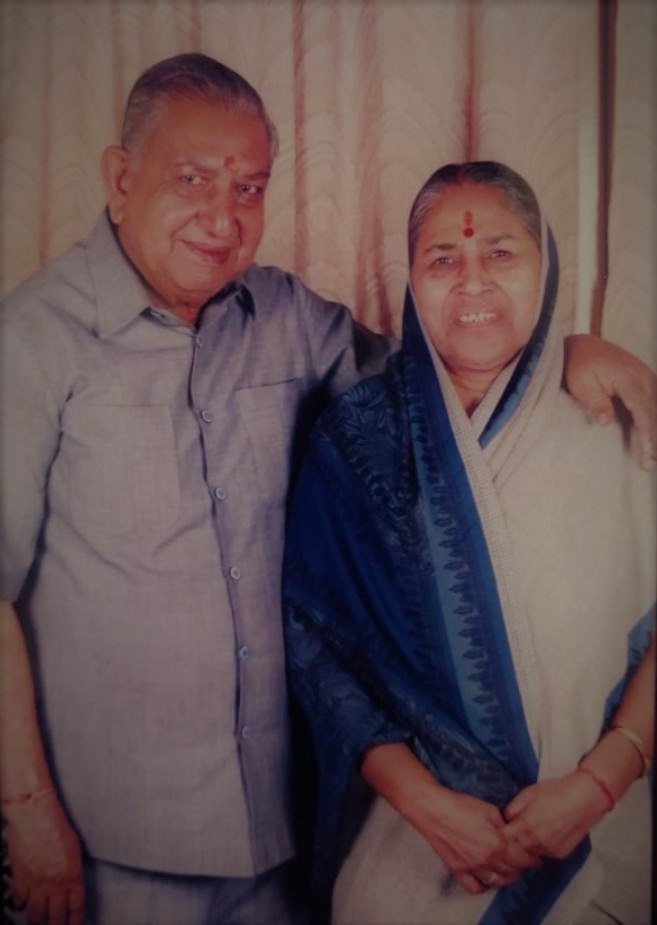

My late grandfather was a simple man. He grew up in Rajasthan and helped his elder brother farm.

Upon realising that the older sibling was taking advantage of him—minimal rations for food, some scraps for cloth and no money—the elders intervened, and my grandfather moved to Hyderabad to eke out a living for his wife, and their five children.

With help from family, he set up a small business, selling edible oil. It did well enough to meet their basic needs—“mota khana, mota pehnna, mast rehna,”—my grandmother often says, recalling the times.

It simply meant that coarse cloth and wholesome food was all they needed for a good life.

The lady of the house made do with a handful of sarees, while younger kids used books passed down from the older ones. Cloth bought from the wholesale market sufficed for all their clothing needs.

As the years went by, the business took off, and the family’s fortunes turned. This began to reflect in Bapu’s style as well—well-oiled hair, jutis and a safari suit.

Come hail, storm, or the 500 days of Hyderabad’s summer, if my Bapu stepped out of home, this was his attire. (While Bapu means ‘father’, I used it for my grandfather.)

At approximately Rs 40 per metre, the safari cloth was a luxury. Along with the tailoring cost of Rs 45-50, this safari suit, once made, would last years.

You would be lucky if you could get basic tailoring mends done at that rate today, forget getting a fully-stitched safari suit for an adult man.

While it appealed to the masses, it certainly wasn’t an affordable piece of clothing.

The appeal of the safari suit

It was the cultural elite of the society—the educated middle or upper-middle class—whose acceptance of the outfit adorned it with qualities not necessarily intended.

Many of them still entertained a hangover of its colonial past, so those who held positions of power—like businessmen and bureaucrats—were considered by themselves and others—to be a class apart.

When a sarkari babu (government officer) or baniya (Marwari businessman) stepped out of his home in a safari suit, the sheen of the outfit accorded him a sense of respectability and sincerity.

Geeta Khanna agrees. She says, “Post-independence, the British ‘hangover’ has unfortunately lingered on way too long, and the safari suit was an acceptable formal/official outfit for the ‘summer’ of India. It also spelled prosperity and an anglicised mindset that was considered superior.”

She is the principal director of the Hirumchi Styling Company, which provides creative and design solutions in India and abroad.

From the African bushes to Indian bureaucracy—the long journey of the safari suit

Ted Lapidus and Yves St Laurent, designers from the style heaven, France, are credited with designing the two-piece safari suit.

Initially intended for safari tours in Africa, variations of the suit can also be traced to the uniforms of the British Army stationed in South Africa during the Second Boer War.

The soldiers needed light and breathable clothing to be active in the heat. For this, their uniforms had to be made of cotton to keep them cool. The button-down shirt would have four large pockets on the chest and waist areas so that they could carry bullets, weapons, and binoculars, perhaps a bottle of water. The shirt had a large collar and a belt at the waist, which kept everything together; and the pants too would come with pockets.

In the book Fashion and Masculinities in Popular Culture, Adam Geczy and Vicky Karaminas explore how popular culture aided the general acceptance of the outfit.

The tailored suit gained popularity during the 1930s and continued to be fashionable attire for men up until the seventies when the unisex safari suit became du jour. While the tailored suit is associated with the ‘Establishment,’ the safari suit made popular by Yves St Laurent, represented adventure and freedom from life’s constraints (like that offered by the hunt) and worn later by Roger Moore as James Bond. As Sarah Gillian suggests, the suit initially signified ‘sobriety, simplicity, conformity and restraint’, the man’s tailored suit functions to construct an image of an idealized male body.’

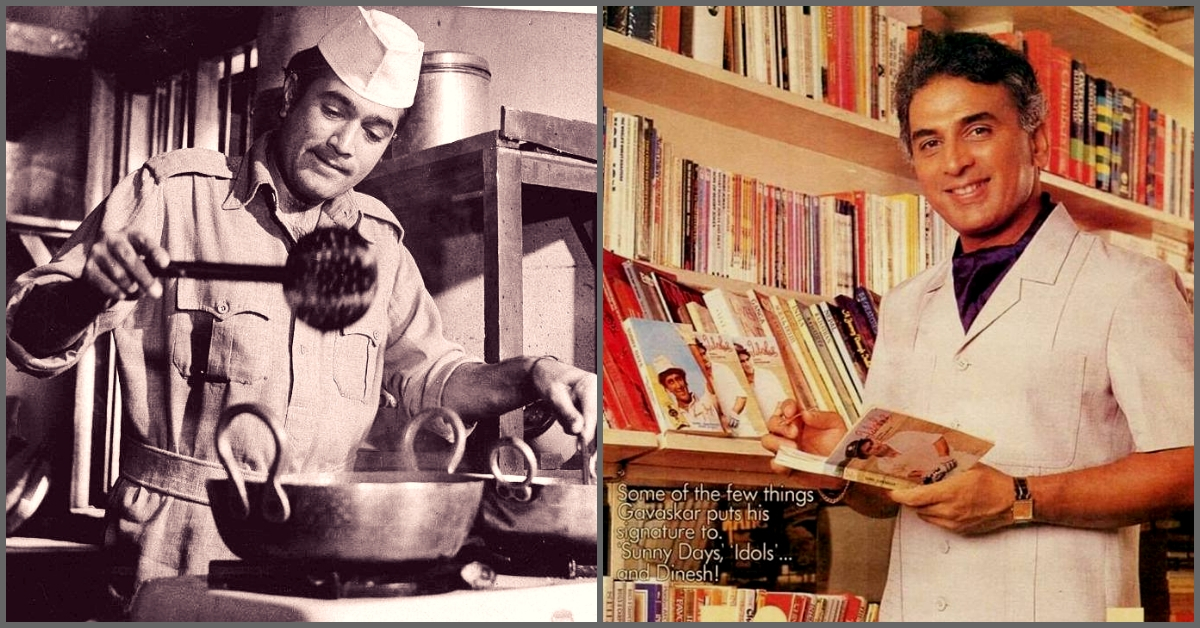

The 007 fandom in the western world and that of the ‘angry young man’ in Indian cinema caused people to imitate their styles. Young employees of corporate organisations and bureaucrats wore them to the workplace as Little Master Sunil Gavaskar modelled them in advertisements, while actors Rajesh Khanna and Vinod Khanna wore them on the screen in dazzling colours.

Politician and bureaucrat Kunwar Natwar Singh was commonly seen in the outfit. As a young diplomat in Indira Gandhi’s secretariat in 1966, he was part of a group of six, of varied ages, from different backgrounds and mother tongues. But they all shared a similarity.

“Seven out of seven of us wore safari suits,” said Mr Singh. “That’s how common they were.”

Another politician, SMI Asseer, told the India Today magazine that he had as many as 25 safari suits in his wardrobe. Similarly, renowned industrialist Rahul Bajaj seemingly had an inexhaustible wardrobe of the suits.

They seemed to be everywhere—synced with people’s aspirations and their fashion sensibilities.

Rishabh Khandelwal feels that the shirt-like comfort, combined with the suit-like “sophistication” made the safari suit a popular choice for people, ideal for Indian weather.

He is the co-founder and managing director of Hangrr, a custom clothing brand for men. He points out how the “unlined, unstructured” safari suit jackets are similar to military uniforms in style and design.

Rishabh says, “It became easier and inexpensive to produce. Considering the socio-economic landscape of the time, it found the perfect fodder to reach mass popularity.”

Raymond, Vimal and DCM Textiles became some of the foremost suppliers in the country. However, around the same time, the 80s, he notes how the outfit began to lose its relevance in the west.

“With a slimmer silhouette governing the world of fashion, the safari suit started losing its dominance.”

The relic of a bygone era

The liberalisation of the 90s opened up India’s economy to a host of western products. It also marked a shift in the country’s geopolitical landscape at the turn of the century. We could bid adieu to the pains of colonialism and move away from the uncertainty of post-colonialism, and finally herald a new kind of modernity.

One such change was in the representation of ideals through clothing.

Khadi, for instance, was a symbol of nationalism during the struggle for Indian independence, when one was not simply accepting a piece of cloth made from a particular yarn—the crucial point was the rejection of foreign fabric.

When viewed in the “objective” light of the present, far from the yoke of colonialism, khadi was losing its sheen.

Dipesh Chakrabarty explains this change in his paper Clothing the political man: A reading of the use of khadi/white in Indian public life.

Khadi, once described by Nehru as ‘the livery of freedom’ and by Susan Bean (to whom I owe this quote from Nehru) as the ‘fabric of Indian independence’, now stands unambiguously for the reverse of its nationalist definition.

I have therefore read it as the site of the desire for alternative modernity, a desire made possible by the contingencies of British colonial rule, now impossible under the conditions of capitalism and yet circulating insistently within an everyday object of Indian public life, the (male) politician’s uniform. I do not think that khadi convinces anybody any longer of the Gandhian convictions of the wearer but if my reading of it has any point to it, then its disappearance, were it to happen, would signify the demise of a deeper structure of desire and would signal India’s complete integration into the circuits of global capital.

Although khadi and the safari suit are less common today, they have not yet been rendered irrelevant. Whether for the sake of nostalgia or as experiments of retro fashion, these icons have been etched in the patchwork of Indianness.

Rishabh notes that there has been an increased demand for safari suits over the past few years, with the attempts to “bridge the gap between the old and the new, and provide safari suits with a modern fit and cut”.

He tells me about designing clothes for a recent beach wedding, where the party was dressed in light blue and beige safari suits, which were “structured, sweat-resistant and wrinkle-free fabrics”.

He adds, “They were slim-cut like modern suits and remained airy for a perfect beach wedding.”

Apart from his team at Hangrr, he tells me that designers across the world are incorporating similar designs into their clothing lines. Some examples are four-buttoned military jackets with shorts and safari-style shirts and jackets.

Also Read: #IconsOfIndia: How an Idea, an Ad & Some Italians Got us the Auto Rickshaw!

He concludes, “The traditional colours, patterns, cuts and designs might no longer be relevant, but innovation and modern techniques will keep safari suits trendy for quite some time. And, like everything else, personalisation plays a great role in getting it right—we must make the safari suit relevant to the person’s style, taste and need. This has helped us keep this timeless outfit relevant and desirable, not only in India but across the world.”

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167