Teacher Lives in Forests For 20 Years, Uplifts One of Kerala’s Most Underprivileged Tribes!

Eschewing a life of comfort, he wholeheartedly embraced uncertainty, discomfort and risks for the welfare, upliftment and most importantly, education, of an extremely reclusive tribal community who consider him as one of their own.

In 1999, when 29-year-old PK Muraleedharan left for Nenmanalkudy, a tribal settlement in Kerala’s Idukki district, little did he know that his life was to change forever.

Muraleedharan was a volunteer with Kerala’s District Primary Education Project (DPEP), which had to set up Multi-Grade Learning Centres (MGLC) in remote tribal locations across the state and run these as single-teacher schools.

At that time, the only tribal LP (lower primary) school was in Edamalakkudy. It was supposed to cater to children from 28 oorugal (tribal) settlements scattered across the forested region.

Some of these settlements were so far away that it would take an entire day or two for children to even reach the school. Additionally, the trail was dense with wildlife – a major deterrent.

Taking cognisance of these issues, the state education department decided to open single-teacher schools in these settlements, and Muraleedharan was one of the volunteers sent for this mission.

Nenmanalkudy was home to the Muthuvans, a reclusive tribal community scattered across a forest replete with reed bamboo and known for unwavering adherence to ancient customs and practices. Even their kooragal (small huts), unlike most tribal settlements in India, were not in close vicinity of each other.

“There were about 35 children aged between 5-15, who had no prior schooling experience. There were no infrastructural facilities, and the only available option was a small shed, which was a former granary,” recalls Muraleedharan, or Murali Maash as he is lovingly referred by the community, to The Better India.

There were no teaching materials either.

“Let alone a blackboard, the state education department did not even allocate any notebooks or slates for the kids,” he shares. The children didn’t have any clothes other than the ones they were wearing, and there was a severe lack of hygienic practices.

“Also, in the Muthuvan community, children are exposed to the wilderness from the time they are about three months old, and there is no restriction regarding movement. This makes them unaccustomed to closed spaces. So, getting them to sit together in a class was extremely difficult,” he says.

But one thing would prove to be the ultimate barrier—language.

The dialect used by the Muthavans has its roots in Tamil and is exclusive to their community.

“I’d never come across the dialect before, and apart from a few male elders, who could somewhat understand Malayalam, no one knew any language other than their own. Here I was, entrusted with the responsibility of teaching these kids, but how would that be possible when the closest we came to communication in the initial days was through improvised sign language?” he says.

So instead of teaching them Malayalam, Muraleedharan decided to begin by initiating basic hygiene and sanitary practices.

“I would take the children to the nearest stream in the forest so that they could bathe and wash their clothes. That is how the initial months were,” remembers Muraleedharan.

Slowly, he started to pick up their dialect. To familiarise the kids with Malayalam, he began to teach them songs and rhymes and make them sing along with him.

While he was hoping for a positive change, things did not go as planned. The number of children going to school kept dwindling until there were only three kids, who were all from one family.

Muraleedharan couldn’t figure out what had happened, so he began visiting every hut in the area. To his surprise, they were all empty, and there was no sign of human presence anywhere.

“After a three-day investigation, I found out that the entire community had migrated to an ooru (singular for tribal settlement) named Vazhakuthu, where cardamom farming was underway. They were planning to return to Nenmanalkudy only when the harvesting was over,” says Muraleedharan.

What now? Well, where the kids went, so went Muraleedharan. He decided to stay on and continue his role in the new ooru in Vazhakuthu. Here, he would be teaching 55 kids from both colonies.

The classes were held in a small structure named sathram, where teens, bachelors and widowed men lived together.

The sanitary conditions in Vazhakuthu were the same as Nenmanalkudy, and Muraleedharan had to run through the same cleanliness initiatives as before.

His dedication to learning the language eventually broke the ice, and he established a good rapport with the kids. He also adapted his teaching ways to suit their needs.

For example, he understood that they were not used to the four walls of a classroom, and would instead conduct lessons outside. He also began to get more involved in community activities.

As DPEP hadn’t provided these teachers with learning materials or resources, they were left to figure out innovative ways to teach the kids entirely on their own, using a monthly allowance of Rs 750.

Muraleedharan spent money from his own pocket to purchase notebooks, stationery and picture charts for them.

“The charts were all relatively new for the children, as they had never seen most of the things included in them. Slowly, we progressed to writing basic Malayalam, starting with names of things and animals around them,” he adds.

This, too, was an arduous task as there was no common ground between both tongues. So, Muraleedharan taught them how to write names of things and beings from their dialect but in the Malayalam script.

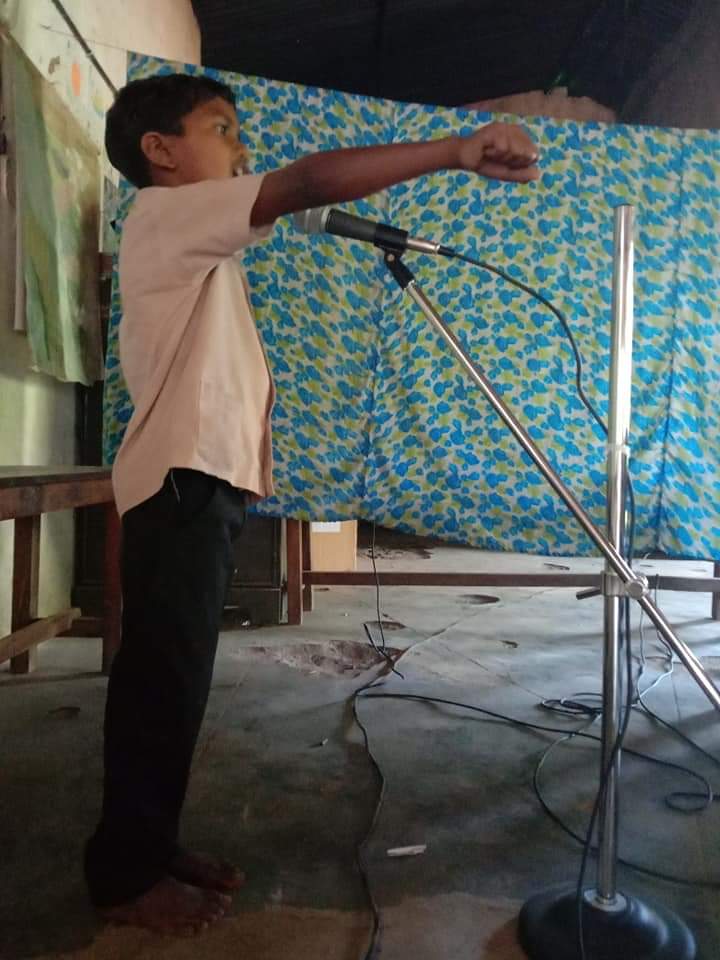

“I also got them to recite and write songs from their community, to help them present something in front of a group. Around this time, DPEP provided me with various multigrade training programmes entirely focused on teaching tribal kids from different age groups together. It wasn’t possible to follow the state syllabus here, so one had to improvise with systems like flash cards. This proved to be a rather successful methodology and became a self-teaching tool,” Muraleedharan remembers.

The mechanism also helped him differentiate between kids who were fast learners, and the ones who were not. He then made groups with mixed capacities, where quick learners would help out the late bloomers.

By then, three years had passed, and Muraleedharan became well versed with the Muthuvan dialect. This helped him bridge the gap with the womenfolk and converse with them.

“I would speak to them about the importance of education, and how that could help them in so many ways. There was a time when these parents would consider these classes as a waste of time, but they eventually saw the benefits of doing so,” he adds.

And what were those benefits though? Lower Primary was all well and good, but how could these children go beyond that, to the world outside?

This mode of education could never equal the teaching methods in mainstream schools or their syllabus. Another major roadblock was was that the kids were much older than their city or town counterparts.

The UP (upper primary) schools were in towns like Adimali and Munnar, which required travelling for a day through the jungles on foot and then taking a bus. The parents were simply unwilling to take the risk.

“I was adamant and wanted to help a few deserving kids progress further, so I took a risk and managed to successfully get them enrolled in a school in Adimali in 2003. I was responsible for getting them to school and home safely,” Murali remembers.

All this time, Muraleedharan lived with the Muthavans at their sathram and ate whatever they would cultivate and consume themselves, mostly including paddy and ragi.

Muraleedharan also helped the tribal community become aware of the local governance system and how things worked. Seeking help at both political and government levels, he helped them get voter IDs as well as ration cards.

In 2008, the increasing wild animal attacks forced the community to move from Vazhakuthu to an area named Olakkayam. A few huts already existed there, and the children from these houses also became Muraleedharan’s students.

This move proved beneficial for the Muthuvans, in terms of a stable income. Though they were traditional farmers, they would rarely produce anything other than grains and cardamom. Thanks to Muraleedharan’s intervention, they began growing and selling pepper.

“The Employment Guarantee scheme was already functioning across the country, and I felt that it would benefit the community, so I travelled to Munnar, where I met the regional scheme coordinator. He came back with me to collect the necessary documents of all interested individuals. By this time, Kudumbashree had also spread its wings in the region and helped the women earn a livelihood through various agrarian initiatives. Things slowly began to look better for the Muthuvans,” he adds.

In 2011, Muraleedharan started an adult literacy drive wherein the children taught their elders to read and write.

During this time, Muraleedharan also penned down two books, Edamalakkudy Orrum Porulum and Gothramanasam, both of which cover the history and life of the Muthuvans in detail.

“There was no electricity in these areas. One had to walk for kilometres to purchase kerosene for lamps. So, simple hearths were what illuminated these oorugal, and I would write these books in that light. This was our life in the woods,” says Muraleedharan.

He also remembers the struggle of feeding the children during school hours. “The midday meal scheme was yet to come, and even then, it would take a long time before our children would be able to access these benefits. I took it upon myself to provide these kids with kanji (rice gruel) at noon, as most of them probably came to study on empty stomachs. It was only after 2005 that I started receiving an allowance of Rs 8 per child from the state,” he adds.

While certain aspects of the education system had significantly become better, Muraleedharan knew that there was a lot of change still needed.

It would, however, take a decade for this to happen.

In 2017, Muraleedharan and other like-minded teachers teamed up and formed a cluster of five single teacher schools in Edamalakkudy, with support from SCERT (Kerala).

“We zeroed in on the tribal community hall in the Mulagathara area, and today, four teachers (including me) run the schools. We also offer to lodge to kids who can’t travel every day. They stay here from Monday to Friday and go home over the weekends,” he explains.

He further shares that this establishment has managed to progress from the initial multigrade structure to a class-like system, which follows the state syllabus for tribal schools, mainly because most kids have learnt Malayalam by now.

As they were now following the class system and lodging, the kids had to be provided with three meals and evening snacks.

“But we only had funds for midday meals. Thankfully, many of our friends, folks at SCERT as well as VV Shaji, a social activist and educationist, offered to help. In fact, Ramesh, a research officer from SCERT, became a close acquaintance. I also contributed eight months’ salary for this purpose, ” adds Muraleedharan.

Finally, the Edamalakkudy panchayat offered to help, and since January last year, the funds to provide the meals for morning and night is supplied by them. The local body also provided an amount of Rs 3.5 lakh to upgrade the school.

“With that money, we were able to buy chairs and desks for the kids, as well as necessary resources like whiteboards, mic sets, a computer, a projector as well as a generator for the school, since electricity is still a problem here,” he proudly adds.

The school even has a library, about which you can read more here.

As for the kids who were staying at the school, Suneesh Babu, the DySP of the Janamaithri police station, and SI Fakhruddin and ASI Madhu in Munnar, provided them with mattresses and pillows.

In addition to that, they also bought bags, umbrellas, notebooks and other supplies for the kids and chairs for the teachers.

Muraleedharan says that the constant monitoring from SCERT researchers has been helpful. There is immense support from all these quarters as well as national bodies like the Child Rights Commission and the Parent-Teacher Association (PTA).

“Today, I can say that the school gives equal value to academics as well as art and cultural activities. I feel that these kids are happy and that they’re no less than any other child across the state,” he says.

As we conclude one man’s two-decade-long journey of bringing education to one of the most remote tribal regions in Kerala, we wonder about his personal life and if that ever came in the way of his selfless commitment to the cause.

“My wife was a teacher, just like me, and passionate about this cause. Sadly, she passed away in 2006. I have a son and daughter, and because of the nature of my work, I had to leave my kids with my parents in Mankulam. I visit them every month end and spend a day or two before returning to the tribal settlements. My son has just completed his degree while my daughter is in Class 8,” he informs us.

Murali Maash is no less than a living legend for the Muthuvans.

You may also like: This Dedicated IAS Officer’s Novel Ideas Are Preventing Tribal Kids From Dropping Out!

Eschewing a life of comfort, he wholeheartedly embraced uncertainty, discomfort and risks for the welfare, upliftment and most importantly, education, of an extremely reclusive tribal community who consider him as one of their own.

We salute this teacher and hope his incredible story inspires you all.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter

Similar Story

‘I Had Decided to Drop Out of IIT Entrance Exams, Until My Dad’s Words Changed My Life’

Ganesh Balakrishnan’s life took a turn when he faced health issues a month before his IIT-JEE exam. Despite feeling disheartened and at the verge of dropping out, his father’s advice helped him overturn his luck.

Read more >

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167