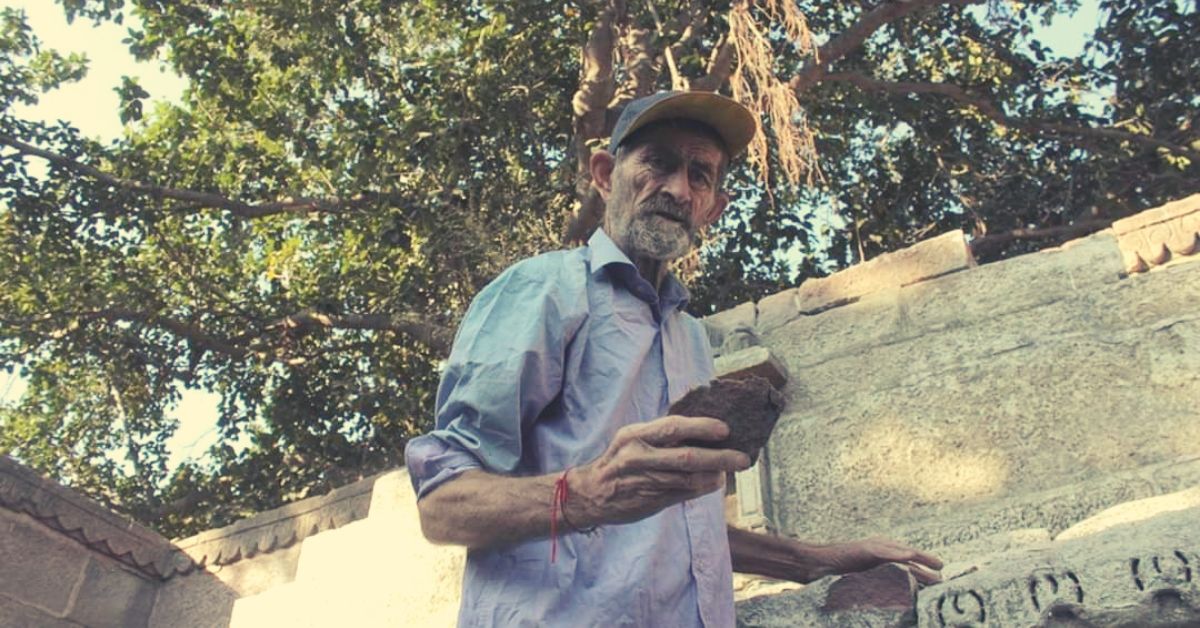

The 70+ Irish ‘Pagal Saab’ Cleaning Jodhpur’s Historic Stepwells For 5 Years!

“My life’s message is that you can work for the betterment of any society, no matter your age, nationality or educational background,” says 70-year-old Caron Rawnsley. #Respect #RealLifeHero #Heritage

Caron Rawnsley, a French-born Irishman in his early 70s, has spent the past five years cleaning Jodhpur’s famed stepwells, locally known as ‘bawaris,’ ‘jhalaras’ (square-shaped open stepwells with steps on three or all four sides), and lakes.

Thus far, he has led efforts to clean 10 precious reservoirs including the Ram bawari, Kriya jhalara, Govinda bawari, Chandpol bawari, Mahamandir bawari, Mahila Bagh jhalara, Tapi bawari and the Gulab Sagar lake.

Once a part of the ancient networks of water storage, bawaris were drinking water points, while jhalaras supplied regular water for religious rites, royal ceremonies and community use.

Here is the explainer in the India Water Portal:

“While the [Mehrangarh] fort is on the hilltop, the walled city of Jodhpur is located at the foot of Chidia-tunk. This made it possible to supply water through a gravity-led system. A vast network of lakes and canals were built in the hills around the city, while wells, bawaris, jhalaras and tanks became a common feature in the plains. Rainwater stored in the lakes uphill percolates through aqueducts or underground channels to recharge wells and stepwells.”

Till the 1950s, Jodhpur met its water needs through this complex network of lakes, canals, aqueducts, tanks, surface wells and stepwells.

However, these stepwells went into disuse, when supply from the Indira Gandhi canal brought perennial water from the rivers in Punjab into this desert city.

Today, many of these architectural marvels that also double up as one of India’s oldest rainwater harvesting systems lie dilapidated.

“When I came to Jodhpur sometime in the latter half of 2014, I saw these beautiful stepwells but was shocked to see these ancient and unique water harvesting systems going derelict. So, I decided to devote my time to cleaning these places and trying to bring them back in good shape,” says Caron in a conversation with The Better India.

A unique bond with India

What drew Caron to India was a long-standing family connection.

His grandfather was the chief railway engineer responsible for the construction of the Bombay (Mumbai)-Baroda (Vadodara) railway line.

“He lived a significant portion of his life in India and was a huge admirer of its great culture. He returned to England post-retirement, and his influence spread into my life,” recalls Caron.

However, his first tryst with the subcontinent was in Pakistan, where he spent two decades involved in the public education and environmental conservation.

“I went to Pakistan in 1988 for volunteer service. I taught at a school in Karachi, which was for children with a hearing impairment. I also worked in state schools in the lower Sindh area, building nurseries with children, teaching them conservation and imparting to them a sense of creativity,” he says.

Through the years, he also taught at some other schools in Karachi, including the famous Karachi Grammar School.

Fed up of teaching affluent students, he moved to the town of Umerkot, which is on the edge of the Thar desert and possesses a mixed population of both Hindus and Muslims.

There, he set up nurseries in every school he went. Mind you, he was doing this without any financial support from non-profits or the local government.

Despite nearly spending two decades there, he was hounded out of the country. “I had very difficult experiences there, and after a point, even the British Embassy treated me as persona non grata. I was stranded there for months, even though I had not broken any law,” he recalls.

India beckons

Caron reached India in 2014.

“When I came to India, I just wanted to see what the country was like. Gradually, I started looking for opportunities to work on environmental issues. I first joined the Barefoot College for about six months to renovate their water harvesting systems. Along with some students doing their Master’s, we worked together to refit the water harvesting system,” recalls Caron.

“Besides their remarkable work in solar electrification, they also plant thousands of trees every year. It’s a lovely endeavour. I thoroughly enjoyed working there,” he adds.

After briefly travelling around the country, he ended up in a village called Hada near Jaisalmer. There he helped build a tree garden with some goat farmers through an NGO run by a local permaculturist.

They had planted nearly 1000 trees, claims Caron, but despite assistance from the local forestry department, things it didn’t work out because the goats ate up all the vegetation.

Following this episode, he wanted to leave for Jaisalmer, but ended up in Jodhpur “by chance.” Once he saw its famed stepwells, he decided to stay.

Lone struggle

Despite reaching out to various municipal authorities and non-profits in the city, there was no definitive response or assistance on the subject of cleaning these stepwells.

He decided to go at it on his own, and employed a few workers to help him out.

“Although some locals did offer to volunteer, I would not see them again. That’s because these water bodies had become very dirty, particularly the lake. It was unpleasant work like unloading thousands of fish which had died of asphyxiation in the lake. Additionally, the stepwells had turned into drinking spots and latrines littered with garbage,” says Caron.

Assistance finally came from the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, which offered to give him skilled labour. Depending on the number of labourers available, he would either have two or seven workers, cleaning up water bodies.

“When we heard about him, we lent our support, and requested him to start cleaning these water bodies as per a certain plan. We requested the government for assistance and adopted some of these water bodies from the municipal corporation. We portrayed Caron as a role model because we felt that people could be inspired/influenced by him,” says Mahendra Singh Tanwar, the convener of INTACH’s Jodhpur chapter and member of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust, to TBI.

However, the local government authorities didn’t help matters. Before cleaning any stepwell, the first thing to note is the configuration of the structure, its depth, and whether it has a working pump already installed by the Jodhpur Public Health Engineering Department (PHED). These installed water pumps regularly lift water for tertiary uses.

“The PHED hands over the responsibility of the pump to contractors, who are a law unto themselves. They defy us all the time, lock us out of the bawaris because they don’t want to pay for the electricity and at times we have also had to request the Jodhpur collector for protection. We need cooperation from the local government authorities.. We have no machinery except for the pump we use given to us by the Mehrangarh Fort Trust, which we use to lower the water level in the bawaris,” says Caron.

Nonetheless, he kept working on it diligently, and soon the local media soon took a keen interest in his endeavour.

Pratyush Joshi, a Jodhpur resident and local activist who worked with Caron for a year, has seen first hand the dedication that has gone into it.

“It’s rare to see a man in his 70’s working with this intense dedication and enthusiasm. From 8 am to around noon and another two hours in the evening, he works with his own hands” says Joshi.

“Today, with necessary approval from the Trust, things have become easier for him, but the work remains very challenging. There are occasions when people support his endeavour, but there are unpleasant confrontations as well. However, seeing him work, it feels like he has taken an oath to bring about positive change to Jodhpur and eventually India,” he adds.

Another volunteer says, “Caron is like a guest in our home, but he has taken the trouble to clean it. We should be inspired by his dedication to cause, and help him further.”

“Caron’s work has really benefited us. We were able to get together various teams of three to four local kids each through him. So, we tell these kids to take up the responsibility for maintaining these water bodies,” says Mahendra Singh.

Assistance

The Mehrangarh Trust helps him with everything—financing and providing him with five to 10 labourers, claims Mahendra Singh.

“The entire cost is covered by the trust and cooperation is extended to him. If Caron feels that there is a lot of work is required at a particular water body or there is a lot of garbage and he feels that the number of labourers/volunteers with him aren’t enough, then we campaign for volunteers on behalf of both the Trust and INTACH,” he says.

Every three-four months, the Trust conduct a large-scale drill with some 200 members, which includes INTACH members, other people associated with this project, social workers and activists. The Trust essentially give them a platform to work.

“Under Caron’s directive, we start the cleaning process as a part of this large-scale drill. We have done this for Navi Bawari, Tapi Bawari, etc. We use 20-50 trolleys for garbage and 8-10 tractors, which helps a lot in cleaning the bulk of the garbage. The advantage is that when 200 people are gathered in one place then locals from nearby mohallas also get curious and ask as to why have so many people gathered in such numbers,” informs Mahendra Singh.

From there an interaction begins with the locals which goes on for a couple of hours. Those cleaning the stepwells tell the crowd about Caron and how a foreigner is cleaning their surroundings, their home, backyard, and that they are neglecting their own home. It seems to have worked.

“We have cleaned a few properly and left them in a good condition. However, in some places people have started defacing them again. We have begun running another campaign so that more people join to maintain them,” he adds.

Protect, preserve and educate

For Caron, this work is essentially about these three things mentioned above.

“These water bodies are home to a thriving ecosystem. You have bats, migratory birds, numerous species of fish, turtles, cobras, sand boas and a whole lot of wildlife,” he informs.

Besides protecting them, however, it’s also about helping school children appreciate the beauty of these stepwells or what he calls ‘underground swimming pools’.

“We must get them invested in protecting the city’s water bodies. These stepwells are a living zoo, and one can learn so much first-hand, instead of watching videos off the internet. A few schools have responded to the idea,” says Caron.

Moreover, these are atmospheric and lovely places to spend time during the hot summer. Like in the centuries gone by, these structures can become great picnic spots, yoga and music centres, particularly the jhalaras, which have an extended platform.

Even the Trust has helped him in this endeavour.

“We wanted to include young people on the streets and areas located around these water bodies, encouraging them to take it forward by maintaining and bettering them further. We also arrange excursions for school kids to these places and introduce them to Caron. They interact with him. These are a few initiatives, which we plan to carry on in the future,” says Mahendra Singh.

Also Read: Using Tech, 26-YO Jodhpur Man Helps Govt Solve 180+ Civic Complaints On Time!

Finally, it’s about water conservation in an era of climate change. So far, the people of the desert regions have canal systems which are bringing water from the upper reaches of India from the Himalayas through the Indira Gandhi canal.

But climate change is going to affect the flow of this water, and this is why these stepwells will play an essential role in the future.

Message to the people

Caron lives in a compound household with a joint family. He had earlier sustained himself on the money he received from his pension, but this eventually got cut off as he began spending more of his time away from the UK.

“I just saved a lot of money. Never spent it on any luxury, and lived in very cheap accommodation all through,” he claims.

For the people of Jodhpur, he has one clear message.

“Get involved. Bring your children to the bawaris, hold picnics there, but don’t contaminate them. These structures are places of sacred heritage and history and gave life to all your ancestors. Meanwhile, administrators must see them as precious heritage structures that need to be protected and open to the public,” he says.

On a personal level, when asked what motivates him to do this work, this is what he said:

“My life’s message is that you can work for the betterment of any society, no matter your age, nationality or educational background. You can contribute to society at any age by educating, raising awareness and stimulating others to think differently about resources and issues of social justice. I’m not representing a vested interest and most certainly am not an ideologist. I represent sanity. I think about valuing our resources, treating them with respect and sharing them effectively with our fellow beings,” he concludes.

Locals once referred to him as “pagal saab” (mad sir) at one time for his incessant cleaning work, but now many of them have seen the light.

You can watch a video of Caron and his team at work here.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.