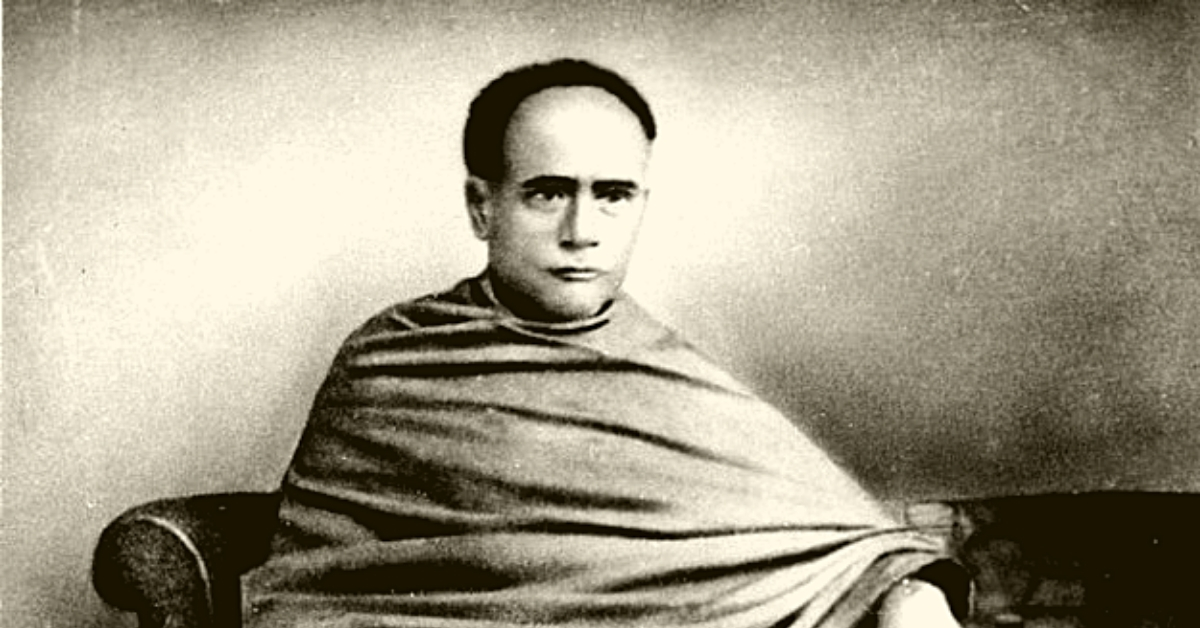

Vidyasagar: The Brilliant Man Who Stood Up For The Women of 19th Century India

A Sanskrit scholar who never shied away from challenging orthodoxy, #Vidyasagar vigorously fought against child marriage, defended women’s right to education, and played a pivotal role in passing the Widow Remarriage Act.

Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar was a legendary educationist, a Sanskrit scholar and a social reformer who not only changed the Bengali alphabet and type but also challenged Hindu orthodoxy by playing a pivotal role in passing the Widow Remarriage Act. He also fought for women’s education and vigorously challenged the barbaric practice of child marriage.

Standing tall against the conservative power centres of Hindu society, Vidyasagar was a man who was way ahead of his times. In light of the desecration of his statue, it is time to remind ourselves about this visionary of modern Indian history.

Born on 26 September 1820 into a poor Brahmin family in Birsing village of Midnapore district, West Bengal, Ishwar Chandra Bandyopadhyay was only six-years-old when he was sent to be educated in Kolkata.

He lived in the house of a family friend Bhagabat Charan in the Burrabazar area.

“The child settled down quickly in a new household where he was taken under the winds of Charan’s youngest daughter, Raimoni. Her maternal care and affection would go a long way in making Ishwar Chandra feel at home and would remain a lasting inspiration in his future fight to improve women’s situation,” writes Kalyani Mookherji in 5 Social Reformers of the World.

He was no ordinary student, passing each exam with flying colours, while also finding a way to support himself financially as a tutor for kids in another wealthy household. With limited means, he continued his education at the Sanskrit College of Kolkata, where he studied for 12 years.

He then picked up a law degree and went on to join Fort William College as the head of their Sanskrit Department. After five years, in 1846, Vidyasagar joined the Sanskrit College as principal.

Here, he opened up admissions to students from other castes, besides Brahmin and Vaidya.

Vidyasagar stated that he had “no objection to the admission of other castes than Brahmanas and Vaidyas, or in other words, different orders of Shudras, to the Sanskrit College”.

He even cited the Bhagavata Puran to argue that there was “no direct prohibition in the Shastras against the Shudras studying Sanskrit literature”.

Vidyasagar, meaning ‘ocean of wisdom’, was a moniker given to him. He was also part of a larger social movement called the Bengal Renaissance, in the footsteps of another social reformer, Raja Ram Mohan Roy.

“What is fascinating about Vidyasagar is the way in which a traditional Sanskrit scholar in a patriarchal society used his command of the ancient scriptures to argue against opponents in his own community, and to campaign for very ‘modern’ reforms, against child marriage, polygamy and the mistreatment of widows. He set an example of enlightened leadership from within cultural or religious communities for the progress of their own people,” writes Dr Sarmila Bose.

She is Senior Research Associate at the Centre for International Studies, Department of Politics and International Relations, University of Oxford.

It was in 1854 that Vidyasagar began his campaign for widow remarriage. The 19th century was a particularly terrible time for women, especially for pre-pubescent girls from poor families, who were forced into marriages with older men. Once their husbands died, they had to spend the rest of their lives wearing white saris, give up all material comforts and live a stigmatised and isolated existence.

Seeing this unprogressive practice play out before his own eyes, Vidyasagar was determined to stamp it out.

In 1854, he began writing against the practice for Tattvabodhini Patrika, a progressive journal. Quoting a shloka from the ancient Parashara Dharma Saṃhitā, a code of laws for the Kali Yuga, he writes:

‘Gate Mrite Pravajite pleevacha patite patau

Panchasvapatsu narinam patiranyo bidhiyate.’

According to Live History India, the translation reads:

“Women are at liberty to marry again, if their husband be not heard of, die, return from the world, prove to be impotent or be an outcast.”

The following year, he filed a petition before the government of the day, seeking legislation that would allow widow remarriage.

Although support for his campaign came from influential figures like the Maharaja of Bardhaman Mahtabchand Bahadur, a lot of back lash came from powerful conservative groups within Hindu society. In fact, the government received more than 30,000 signatures challenging Ishwar Chandra’s petition.

However, his sustained efforts, alongside fellow social reformers finally resulted in the passing of the Widow Remarriage Act on 26 July 1856.

“No marriage contracted between Hindus shall be invalid, and the issue of no such marriage shall be illegitimate, by reason of the woman having been previously married or betrothed to another person who was dead at the time of such marriage, any custom and any interpretation of Hindu Law to the contrary notwithstanding,” read the law.

Despite their success in passing a law, the real challenge was getting society to accept widow remarriage. Ishwar Chandra took the challenge and performed the first widow remarriage in Kolkata on 7 December 1856 on his own dime.

Following India’s first war of Independence in 1857, however, power transferred from the East India Company to the British Crown, and for a few decades, the colonists decided not to interfere in Indian personal laws. For Ishwar Chandra, who sought to abolish child marriage, this series of events came as a blow.

“A congruence of interests between reformers and those wielding political power is clearly a key factor for successful legislative reform. By the time Vidyasagar attacked the practice of polygamy among high-caste Hindus in the 1870s, the revolt of 1857 had created an unbridgeable chasm between Indians and their colonial masters. Indian nationalists were more interested in ‘cultural preservation’, and the British had lost their reformist motives. The campaign failed,” writes Dr Bose.

A similar fate awaited his battle against child marriage.

Disillusioned by the lack of tangible public support, he spent the last two decades with the Santhal tribes in present-day Jharkhand. There, he opened the first school for tribal girls.

Also Read: How India’s 1st Muslim Woman Teacher Started a ‘Beti Padhao’ Movement in 19th Century

It was a mere four months before his passing in March 1891, when the British India administration passed the Age of Consent Act, which legally abolished child marriage, following the efforts of other social reformers who took their cue from the likes of Vidyasagar and Ram Mohan Roy. The scholar passed away on 29 July 1891.

What Vidyasagar did so well is to advance the cause of reform while remaining true to an ancient intellectual spirit. His legacy lives on, particularly in West Bengal. Today, his name is attached to a university, a bridge and even a hall in IIT Kharagpur. More than anything else, however, his real legacy lies in the fact that his ideas remain relevant today.

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.