The Untold Story of India’s 14-YO Female Revolutionary & Her Historic Trial

At 14, she shot a tyrannical British magistrate, underwent a historic trial, and spent seven years in imprisonment. Later, in independent India, she became a doctor.

To honour this nation’s Independence Day, we bring you the fascinating stories of #ForgottenHeroes of #IndianIndependence that were lost among the pages of history.

She was like any other pre-teen girl, scared of the darkness under the table while studying at night. That was before the proscribed books, arms, and ammunition secretly made their way to her study table.

Meet Suniti Choudhury, the youngest female revolutionary of India. She was born to a middle-class Bengali family of the Comilla sub-division of Tippera on May 22, 1917.

At 14, she shot a tyrannical British magistrate, underwent a historic trial, and spent seven years in imprisonment. Later, in independent India, she became a doctor.

The year was 1930. The Civil Disobedience Movement was in full throttle—police brutality was equally strong. Suniti witnessed picketings, processions, and the rapid arrests of men and women—experiences that were elevating her to a new plane of fearlessness.

Around this time, Prafulla Nalini Brahma, her immediate senior at Faizunnisa Girls’ High School, mentored and supplied her with the books—mainly the revolutionary literature banned by the British. “Life is a sacrifice for the Motherland”—the words of Swami Vivekananda shaped her beliefs.

Suniti became the Major of the District Volunteer Corps. She led the parade of girls when Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose was in town to address the student organisation. Prafulla asked Bose about his thoughts on the role of women in the revolutionary movement. Without a pause, Bose replied, “I’d be happy to see you in the front row.”

Meanwhile, ‘Chhatri Sangha’, the female wing of the organisation, affiliated to ‘Yugantar’ was training young girls, while the smartest and bravest of the trainees passed on information, papers, arms, ammunition, and money, for the revolutionaries.

However, Prafulla, Santisudha Ghose, and Suniti Choudhury demanded more effective responsibilities—to stand equal to the boys!

When some of the senior leaders expressed their doubts on little girls going into action, Suniti retorted, “What good is our current dagger-and-stick play, if we shy away from real action?”

Finally, Biren Bhattacharjee, one of the absconding leaders, secretly interviewed the girls and declared the three to be of outstanding courage.

Their practical training began under the supervision of Akhil Chandra Nandi, president of the Tripura Students’ Organisation. They skipped school, sneaked out to the Maynamati Hills away from the dense town, and fired practice shots.

The key challenge was not to shoot targets but to manage the back kick of the revolver. Suniti’s index finger did not reach the trigger properly, but she was not ready to give up. She used her long middle finger to fire her lethal shots from a small revolver of Belgian make.

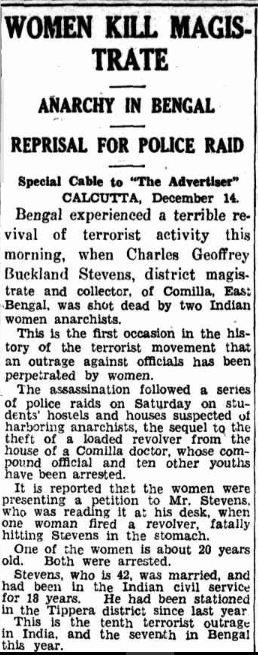

Their target was the District Magistrate Charles Geoffrey Buckland Stevens, a man who would stop at nothing to destroy the Satyagraha. He threw all the leaders into prison, and harassed every non-violent Indian who raised a voice. Something had to be done to set the balance right, and Santi-Suniti were going to execute it.

At 10 am on 14 December 1931, a carriage stopped before the District Magistrate’s bungalow. Two teenagers descended from it, giggling, brimming with excitement. Both had a silk wrapper around their sarees, perhaps to beat the cold! The coachman drove off with some haste, even before they could cross the long corridor.

The girls sent an interview slip through the orderly, and the Magistrate came out, along with Sub-divisional Officer (SDO) Nepal Sen.

Stevens glanced at the letter passed to him. The girls, Illa Sen, and Meera Devi as per the signatures, were appealing to the Magistrate for a swimming club. The use of a much-flattering “Your Majesty” and some otherwise incorrect English left no doubt about their sincerity. Illa also identified herself as being the daughter of a police officer to win over the “majesty’s” sympathy.

The girls were getting impatient for a clean window. They requested Stevens to sign the letter as a reference. He went to his chamber, and soon returned with the signed paper.

That was his last move before the shots rang through the house. The notorious magistrate’s last sight was the two girls, now without the silk wrapper, pointing two revolvers straight at his heart.

The SDO jumped in too late. When people gathered to capture the two teenagers, Santi and Suniti did not defend the heavy thrashing that ensued.

They came prepared for all the upcoming torture—pricking pins on their fingertips to increase their endurance of pain—so they were not going to break under beatings or speak a word about their secret organisation. They kept a straight face even when molested under the pretense of body searches for weapons.

The news spread like wildfire.

Also Read: The College Girl Who Ran a Secret Radio Station To Fuel India’s Freedom Struggle

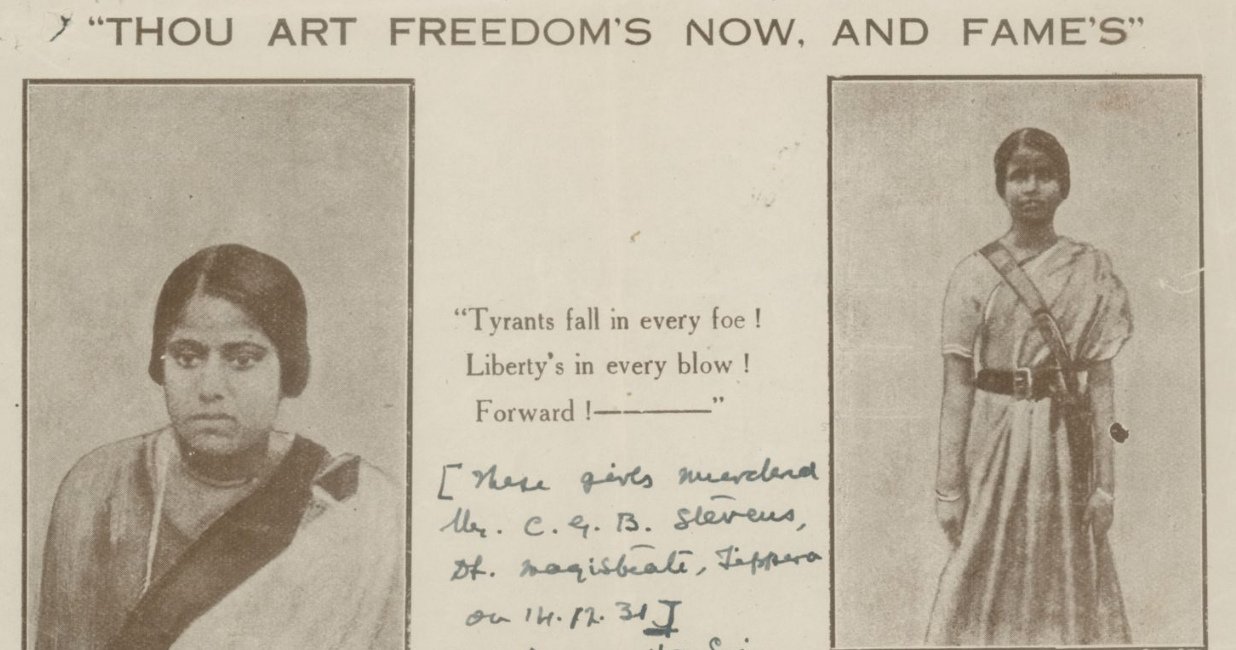

The revolutionaries distributed pamphlets about the brave girls. People adored the photograph of Suniti in her Major’s uniform, a single line written beneath it—Rokte Amar Legechhe Aaj Sorbonasher Nesha—The burning desire of destruction rages in my blood today.

The deed was well done, but the girls had miles to go yet.

When the trial began, the courtroom was struck in disbelief over their appearance. They were beaming and enjoying the awkwardness of the spectators—they turned their backs to the judge and all other court members because they were denied chairs to sit. They would not budge to show respect to any person if they were not offered basic courtesy first.

When SDO Sen came as a witness and started cooking up stories, they shouted “Great Liar! Great Liar!” so loud that the courtroom was in mayhem. Nobody could get away with offending them, because the two little girls seemed to fear no court.

They sang patriotic songs from the police van to the courtroom and back, offering radiant smiles to people gathering near and blessing them from far.

Their smiles faltered only when the verdict was out. The audience saw a different side of them, two depressed faces over the sheer disappointment. It was lifetime imprisonment, which meant they missed their window of martyrdom. They were heard on the way, fuming, “This should’ve been a hanging! Hanging would be so much better!” stunning news reporters into silence.

The authorities never backed down on the effort to break them. Prafulla was suspected as the chief conspirator and thrown into jail. Later, she was under strict house arrest, where after five years, she died from lack of medical care.

Santi was kept in second class with the other revolutionaries, while the younger Suniti was pushed to the third class, with the thieves and pickpockets.

This also meant zero human rights from deplorable food to bad clothing. Suniti didn’t seem to mind either. She went on with her daily jail chores, regularly hearing about the police atrocities her old parents faced, how her elder brother was arrested. The news of her younger brother becoming a hawker in the streets of Calcutta, his death from sickness and starvation, reached Suniti but failed to break her calm resolve.

The petty criminals adored this girl of a regal yet humble attitude. Bina Das wrote about one incident where after a Ramadan fast, a woman fiercely insisted that Suniti have her glass of sweetened saline water because she believed the young lady to be more deserving of the treat.

The ordeal ended on 6 December 1939. The amnesty negotiations before the Second World War caused their release. By then, Suniti was 22—a woman without formal education, with only her brother to help.

But the revolutionaries never quit.

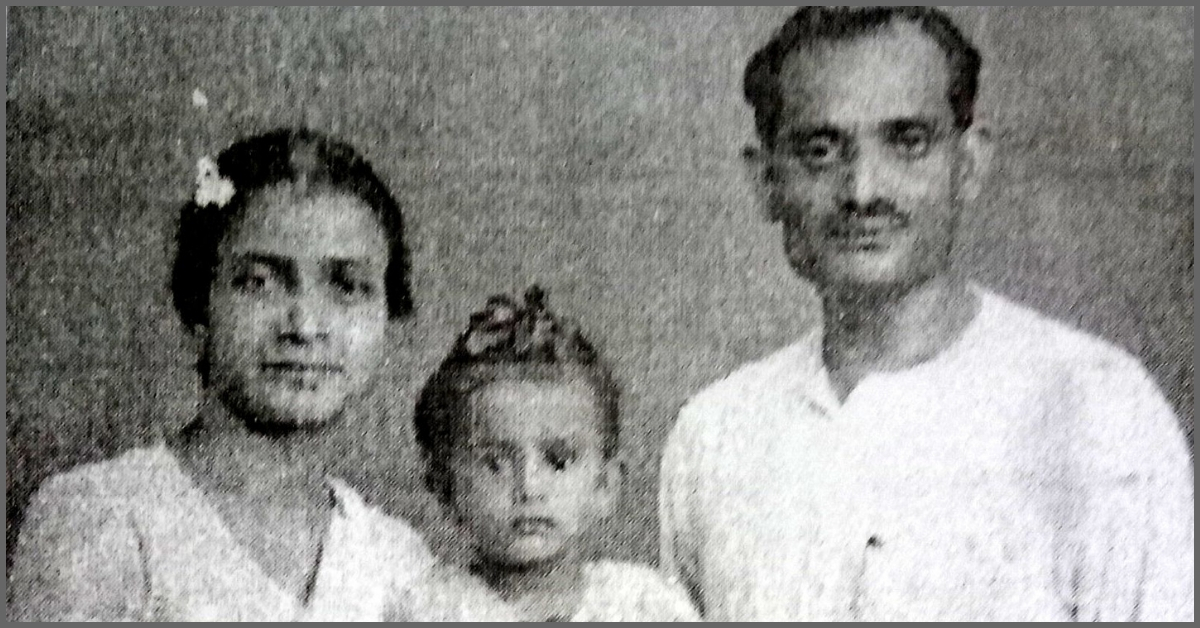

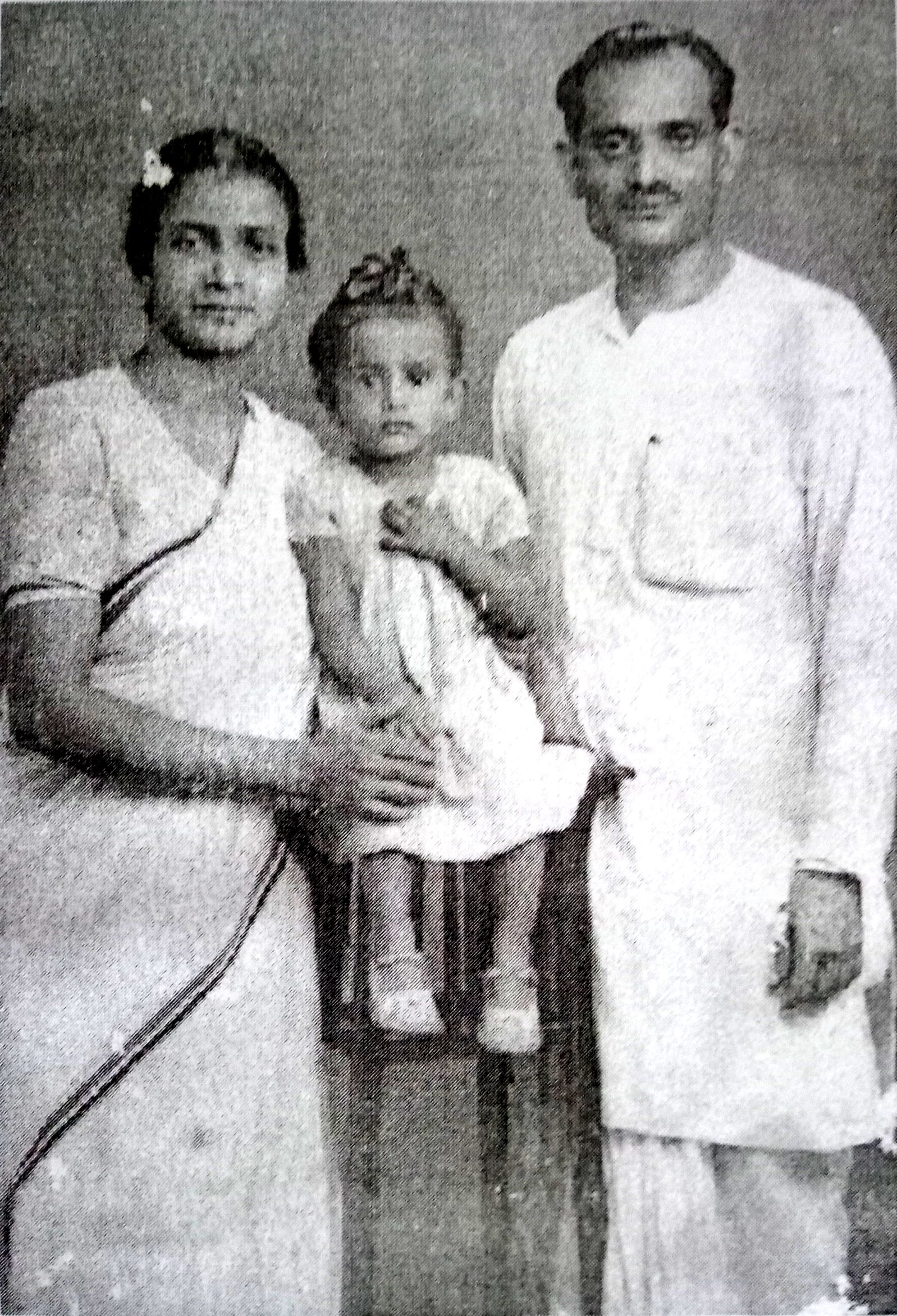

She started over gallantly, put all the efforts in her studies, passing in the first division of the pre-university course (ISc) from Asutosh College. She carried on to Campbell Medical School for the Licentiate in Medicine and Surgery (LMS) and finally secured admission in Calcutta Medical College in 1944. After completing the MB (now MBBS), she married Pradyot Kumar Ghose, another activist and former political prisoner, her brother’s friend.

Suniti’s skill matched by her kindness and dedication, quickly made her a reputed doctor in Chandannagar, where the people lovingly called her “Lady Maa” (Lady Mother).

In the first general elections of 1951-52, Dr Suniti Ghose was offered a contesting ticket from the Congress and the Communist parties, which she firmly refused. She was not interested in political plays which already undermined her contributions.

She endured political battles for her career thereafter.

Suniti was not only financially independent, but also helped her brothers in their business, and contributed to the care of her paralysed parents. She loved children and nature, teaching them gardening, swimming, and nature studies. She encouraged her daughter, Bharati, to celebrate different occasions and festivals.

You May Also Like: At 21, This Feisty Bengali Woman Etched Her Mark on India’s Freedom Struggle!

She breathed her last on January 12, 1988, leaving behind a legacy of patriotism, bravery, kindness, and inspiration.

(Edited by Shruti Singhal)

Like this story? Or have something to share?

Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167