This Legendary IFS Officer is The Only One With Two Species Named After Him!

"Sunil Limaye is definitely among the very best forest officers I have ever come across. When I saw him for the first time, I thought he was strict and unfriendly, but after working with him for three years, my perceptions have changed completely."

In Maharashtra, it isn’t hard to come across news stories of wild animals straying into human settlements, particularly in major urban centres like Mumbai, Pune, Thane, or recently, Nagpur.

Many conservationists believe that once people began encroaching into forests did these animals sought to venture into human habitations. Everyone needs some space, particularly animals. If people don’t invade, these animals won’t venture into their homes.

It may sound simple in theory, but practising it will be practically impossible. Population explosion is a beast, and it cannot be controlled. It’s a stark and bitter truth that will make human-wildlife conflict more frequent than ever before.

So how do you stop the denizens of the wild, particularly tigers and leopards, from straying into your communities?

However, the bigger question is, are we even framing this question correctly?

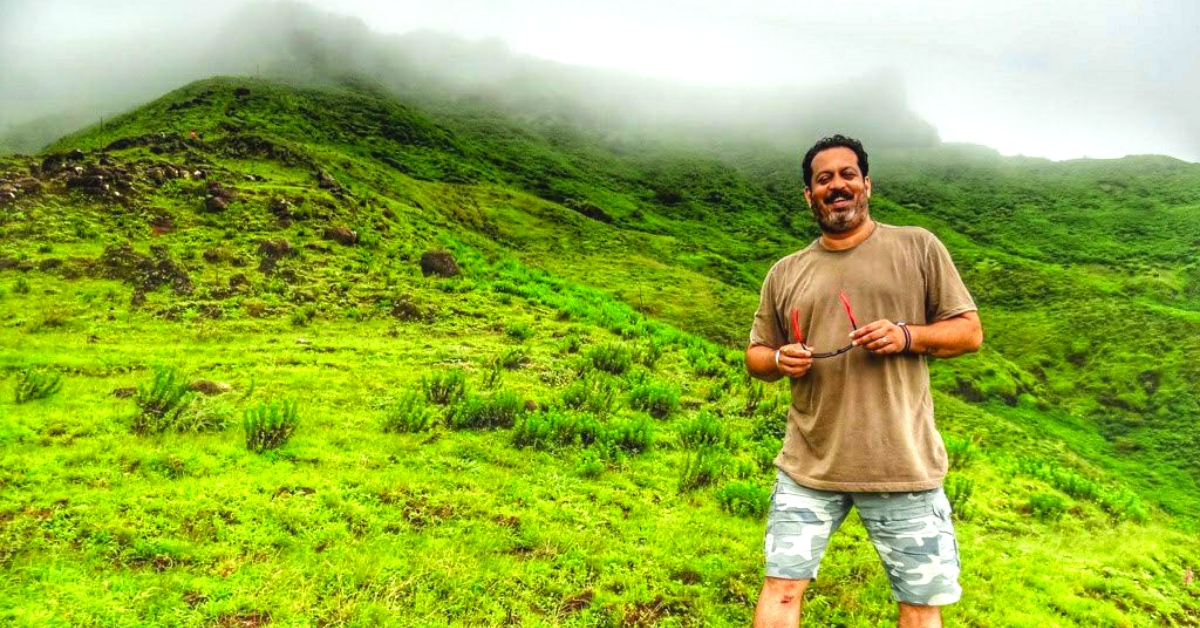

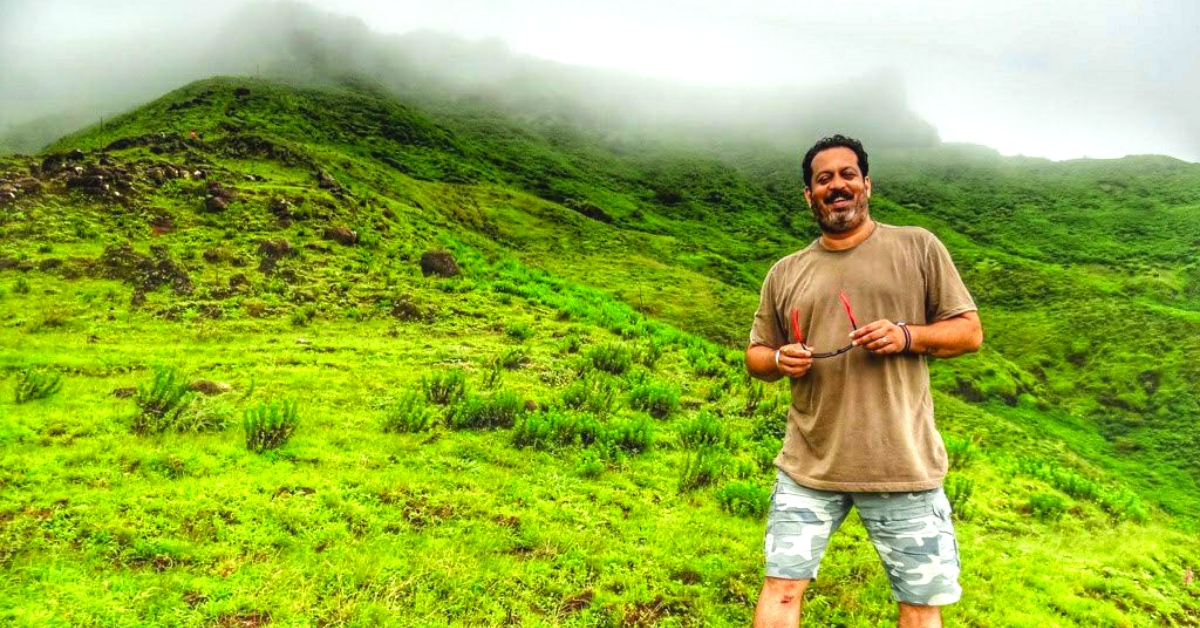

Meet Sunil Limaye, currently Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests (Wildlife-East) who believes, “One cannot teach leopards, but one can teach people how to behave. Human-wildlife conflicts aren’t because of leopards but because of us.”

Perhaps, what we need to ask is, instead of expecting the animals to adapt to us, can we adjust our lifestyle to prevent man-animal conflict? Or can we replace human-wildlife conflict to human-wildlife cohabitation?

Limaye along with wildlife biologist Dr Vidya Athreya, started an initiative called Mumbaikars for SGNP (Sanjay Gandhi National Park) in 2011 to address the human-leopard encounters.

Adjacent to the ever-expanding Mumbai metropolis, the SGNP has, over the years, seen its fair share of this conflict. What this initiative worked out was a model for mitigating these conflicts, which has today been adopted by states like Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand.

Early days

Hiking, trekking and navigating through the jungles of Kolhapur district in southern Maharashtra during his college days, Limaye always shared a close bond with nature. However, for the 1988-batch Indian Forest Service officer, nature conservation wasn’t his first choice.

“My first choice was joining the Indian Army, but I couldn’t make the cut. When that option fell, getting into the forest service became a default choice,” says Limaye, in a conversation with The Better India.

After acquiring the necessary academic qualifications in Forest and Wildlife Management, he joined as Deputy Conservator of Forests (Wildlife) in Kolhapur. “Thus, what was once my hobby now became my job,” he adds.

Working with local communities

While tackling encroachment by major commercial entities on forest land is a significant concern, particularly around urban centres like Mumbai, Thane and Pune, what requires closer attention is how to deal with locals, particularly those from tribal communities, who have, for generations, depended on these forests for years for their livelihood.

In other words, how do you balance the requirements of conservation with their day-to-day needs?

The team approached the local community for the protection of forests, offering them alternative job opportunities. Those dependent on the forest for firewood or other sources of livelihood were given LPG gas through a government scheme to reduce their dependence on the forest.

“The government paid nearly 75 per cent of the cylinder’s price and only 25 per cent by individual tribal folk. In the first year, this 75 per cent amount was paid for 12 cylinders, and the next year for eight cylinders and slowly but surely, we weaned them away from firewood. But how do they refill the LPG? They need employment,” says Limaye.

Under various schemes, the forest department employed them to patrol and protect the forest area. For tribal communities living in the vicinity of these forests, encroachments came in the form of using forest land for agriculture purposes. How do forest officials deal with it?

In 2006, Parliament enacted the Forests Rights Act (FRA), under which, before 13 December 2005, if you have encroached on forest land for agricultural purposes, a maximum of 10 acres of land will be given. For the most part, this provision worked reasonably well. The State Government gave land to those ‘eligible encroachers’.

“After that, with the help of the tribal department, we advised them on how to improve productivity on their farmlands because traditional methods weren’t accruing much income,” says Limaye.

According to Poorest Areas Civil Society, an advocacy group, under the FRA, two types of claims to forest land can be made:

Individual claims – these are claims made by individual households for up to 4 hectares of land that they live on and use for cultivation and livelihoods. The family has to have been living on and using the land since before 13 December 2005.

Community claims – these are claims made by a community for land on which community facilities are built, e.g. schools, playgrounds, health centres, or for wider areas of forest land that the whole community is dependent upon for their livelihoods.

In areas where claims coming under Individual Forest Rights (IFR) and Community Forest Rights (CFR) have been accepted, these communities have begun planting fruit trees with assistance from the forest department, thus ensuring a steady income.

“We are also employing members of the tribal community for all forest conservation-related operations. Our message to them is that the forest belongs to you, but you have to save it for the future generation. Working alongside the Tribal Welfare Department, we are helping them acquire environment-friendly LPG cylinders and solar panels, besides encouraging them to plant, grow and adopt the forest,” claims Limaye.

Dealing with human-wildlife conflict

Launched in November 2011, Limaye as Field Director of the SNGP, teamed up with Dr Vidya Athreya and a multitude of wildlife researchers to study leopard movement, their dietary habits and began advising people, particularly from the tribal communities, on how to minimise conflict.

“We started a project to raise awareness among locals about leopards. Our advice was that that if they don’t want leopards to stray into their area, certain rules must be followed,” says Limaye.

For example:

• Forbidding stray dogs from entering forest areas and children from playing in the open during evenings or early mornings because that’s when the leopard moves around.

• The tribals were also advised that good lighting and even some light music can alert leopards to the presence of people and keep them away.

• Moreover, ensuring a neighbourhood free of garbage reduces the presence of feral dogs and thus, its predator, the leopard.

“We told them that if you want to live in the vicinity of SGNP, you must prevent encroachment and learn to live with leopards,” adds Limaye.

However, this initiative wasn’t merely limited to leopards, but also insects, spiders and scorpions. Just outside the SGNP, there is a place called Aarey Milk Colony, where there are a lot of species of small insects. The forest department helped researchers in this domain.

Among the plethora of researchers, Rajesh Sanap, currently a Research Associate at the National Institute for Biological Sciences in Bengaluru, worked closely with the Mumbaikars for SGNP initiative, particularly in the Aarey Milk Colony. His area of expertise includes spiders and scorpions, and he has very fond memories of Limaye’s work.

“An element of this initiative was camera trapping, because of which we came to know about how the leopard moves in the area. All the different data they collected was used to raise awareness among local communities, schools, the municipal corporation, NGOs, media and even the police,” says Sanap, speaking to TBI.

Bringing all these stakeholders on board, they collaborated on establishing a definitive protocol to find solutions for the human-wildlife conflicts in the city.

“Today, when a leopard is spotted, the forest department is called to deal with it while the police are tasked with cordoning off the area to keep crowds away from the spot. This spirit of community participation including all stakeholders has reduced incidences of human-wildlife conflicts.

Limaye is definitely among the very best forest officers I have ever come across. When I saw him for the first time, I thought he was strict and unfriendly, but after working with him for three years, my perceptions have changed completely, adds Sanap.

In honour of Limaye’s work, Sanap has named a new species of spider he discovered after him. It’s called the Jerzego sunillimaye, which is only the second species under the genus Jerzego from India. “I named it after Limaye to honour him and his work,” he says. His findings were recently published in the peer-reviewed journal Arthropoda Selecta.

Mind you this isn’t even the first species to be named after the forest officer. Last year, another researcher named a nocturnal lizard, Limaye’s Day Gecko.

“These gestures genuinely touched me,” says Limaye. The Mumbaikar SGNP initiative has paid off handsomely with barely any attacks reported since 2013.

This initiative is indeed a lesson in how both humans and leopards could peacefully cohabitate.

Reducing human-wildlife conflict—a combined effort

Limaye remembers one tragic instant in May 2013, which did bring home the effect this initiative had on the locals in the area. It was a bittersweet moment for him.

Whenever a leopard would kill a local, the blame would often be directed at forest officials for their apparent inability to contain it within the vicinity of the national park. This was particularly the case in the Aarey Milk Colony area, where a lot of tribal residents lived.

“Many families there would send their children to the nearby school, where the route would go through a small patch of forest. Earlier, a bus would come from Mumbai, and take these children from Aarey to school so that they could avoid that forest patch. When we started our campaign, people soon realised that human-wildlife conflicts were not necessarily because of the forest department or leopards, but other departments who do not fulfil their duties. For example, if you want to ply a bus, you need good roads, and that work needs to be done by the Public Works Department,” he says.

Also, if you don’t want leopards to venture into human settlements, then that area should be well lighted, which is the Electricity Department’s work. If you want the garbage removed, this is the Municipal Corporation’s work. In other words, if you want to stop these human-wildlife conflicts, many departments have to work together.

“One day, unfortunately, a child coming from school decided to take the shorter route through the forest patch. A leopard killed the child. It was bedlam,” he recalls.

“People gathered, camera crews gathered, but when a correspondent asked the mother of the child who had died whether it was the forest department’s fault, she responded by saying the fault lay with those who couldn’t construct a decent road, thus preventing the bus from plying. If there had been a good road, there would have been a bus. If there had been a bus, ‘my son would not have to walk through the forest patch. My son lost his life because of their apathy’, she said,” according to Limaye.

It was an incredibly tragic moment, and she could have easily blamed the forest department or the leopard. But she had realised that it isn’t the leopard’s fault.

“In spite of all her pain, she didn’t blame the leopard. She knew that it’s because some people weren’t willing to do their duty that her son had died,” he adds.

For Limaye, it was indeed a bittersweet moment. While a mother tragically lost her child, what came through her pain was a profound awareness of the situation at hand—a true vindication of the work he had set out to do in 2011.

After his tenure as Field Director came to an end in October 2013, there were no reports of any human-wildlife conflicts until 2017, which saw “seven attacks and one death, the highest in the past 15 years, since 2002,” according to the Hindustan Times.

Also Read: Meet the IIT-Grad-Turned-IFS-Officer Who Helped Save Sikkim’s Forests & Dying Springs

For the residents of the Aarey Milk Colony, who suffered the brunt of these attacks, basic civic amenities remained out of their grasp, with multiple infrastructure projects were eating into the forest area.

If anything, authorities across different levels of government could learn a thing or two from the model set by the Mumbaikars for SGNP initiative.

(Edited by Saiqua Sultan)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.