Sikkim School Teacher Earns Money From Waste, Sponsors Education of Village Kids!

In a brilliant experiment, he upcycled 50000 plastic chips packets into 3000 book covers that were sold to schools of neighbouring villages. And that's just one of his many ideas! #Education #Innovation #CleanIndia

Lomas Dhungel, a 34-year-old science and mathematics teacher at the Government Senior Secondary School in Sikkim’s Makha village, is doing something few in this country are.

Under his ‘Hariyo Makha–Sikkim Against Pollution’(‘Hariyo’ is a vernacular word for green) project started in 2015; he is working towards a sustainable future with the help of his students by recycling waste through multiple initiatives.

But that is not all. He is also generating revenue from the project and using the money to sponsor the education of five local students.

Can it get any better?

“I grew up in a village 15 km away from Makha where I never saw pollution. That changed when I grew older and moved to cities. I could see the distinct difference between polluted and non-polluted areas,” recalls Lomas, in an exclusive conversation with The Better India.

In 2001, Lomas was in Gangtok when he found out for the first time that disposable polythene bags had been banned all over the state. This prompted him to learn more about the ill-effects of plastic, particularly of the single-use variety.

“These two memories form the basis of my motivation to tackle pollution,” states Lomas.

In 2013, he began exploring the idea of recycling all that waste. He soon followed up by collecting garbage from his neighbours, segregating it and selling the dry waste to scrap dealers and recycling units. “However, there wasn’t much success here. I had to think bigger,” he says.

Lomas noticed that Makha had no formal system of waste collection. He was particularly peeved by the locals and tourists, who would litter the streets with empty packets of chips. These had no resale value, so ragpickers would often burn them, resulting in the emission of toxic pollutants.

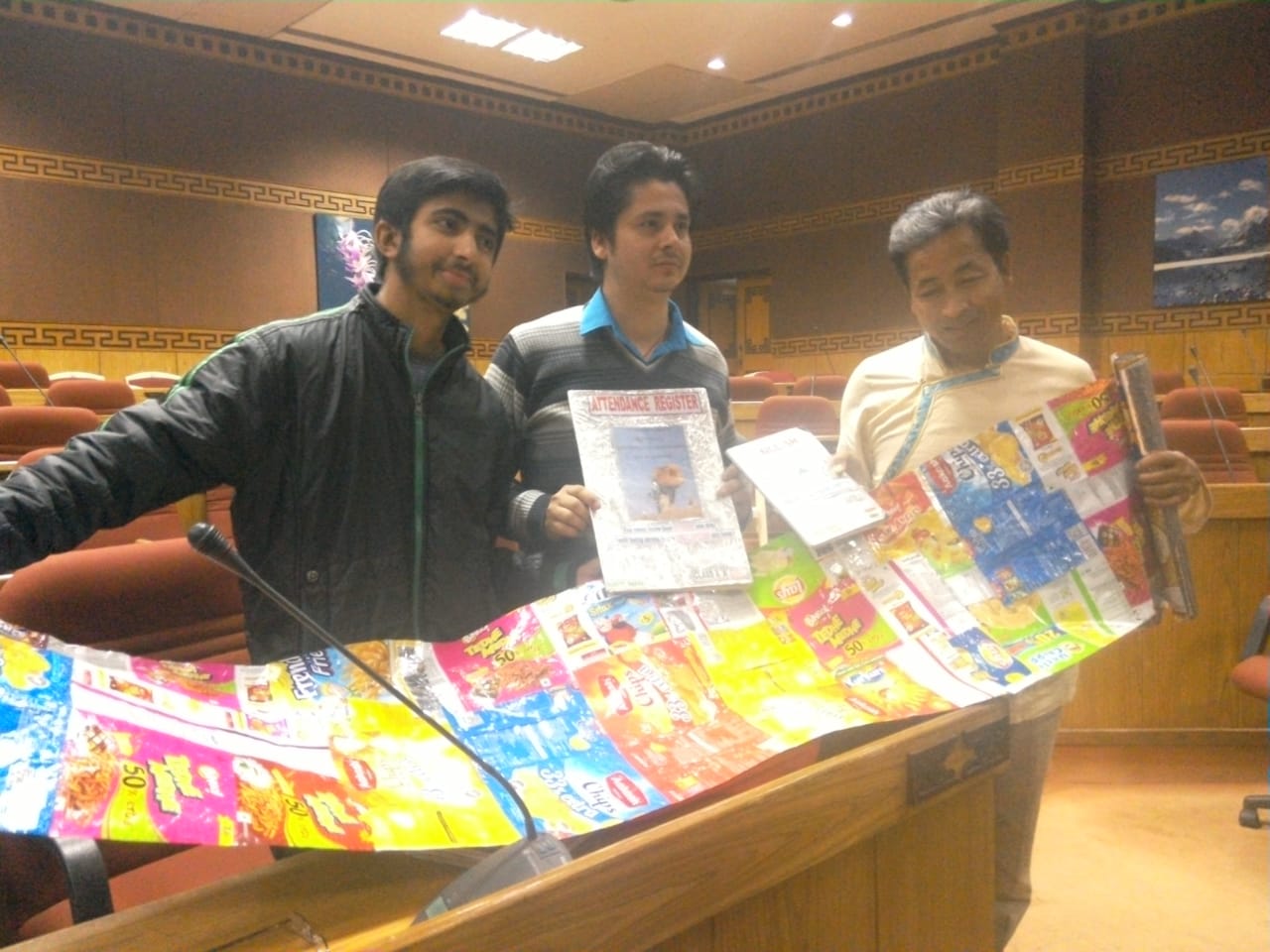

“In 2015, I came up with the idea of collecting these packets, cleaning them, and sticking them together with cello tape to make book covers. I presented this idea to my students and school authorities, and after receiving their approval, I approached students from Class 6 to 8, asking them to bring waste packets to school, while requesting my students from Class 9 and 10, whom I taught physics and mathematics, to clean the packets. We stuck the plastic packets together with high-quality cello tape, and fashioned them into book covers,” says Lomas.

This initiative was a major hit with school students.

So far, students from the school have converted around 50,000 packets of chips into 3,000 book covers, and these are sold to schools from nearby villages.

Through this initiative, they even helped a student, who had dropped out of school because of financial constraints, to resume her studies.

“In fact, we were able to fulfill the book cover demands of one entire school. We are looking to take this further by collecting 50,000 more plastic covers and converting them into book covers.”

In 2017, Lomas began another eco-friendly initiative with motivation coming from seeing students using a single side of A4 papers for their assignments. “All this paper was getting wasted. These sheets are often sold to scrap dealers or burnt without anyone using them,” says Lomas.

He reached out to his school and others in neighbouring villages to give them assignments of students who had graduated.

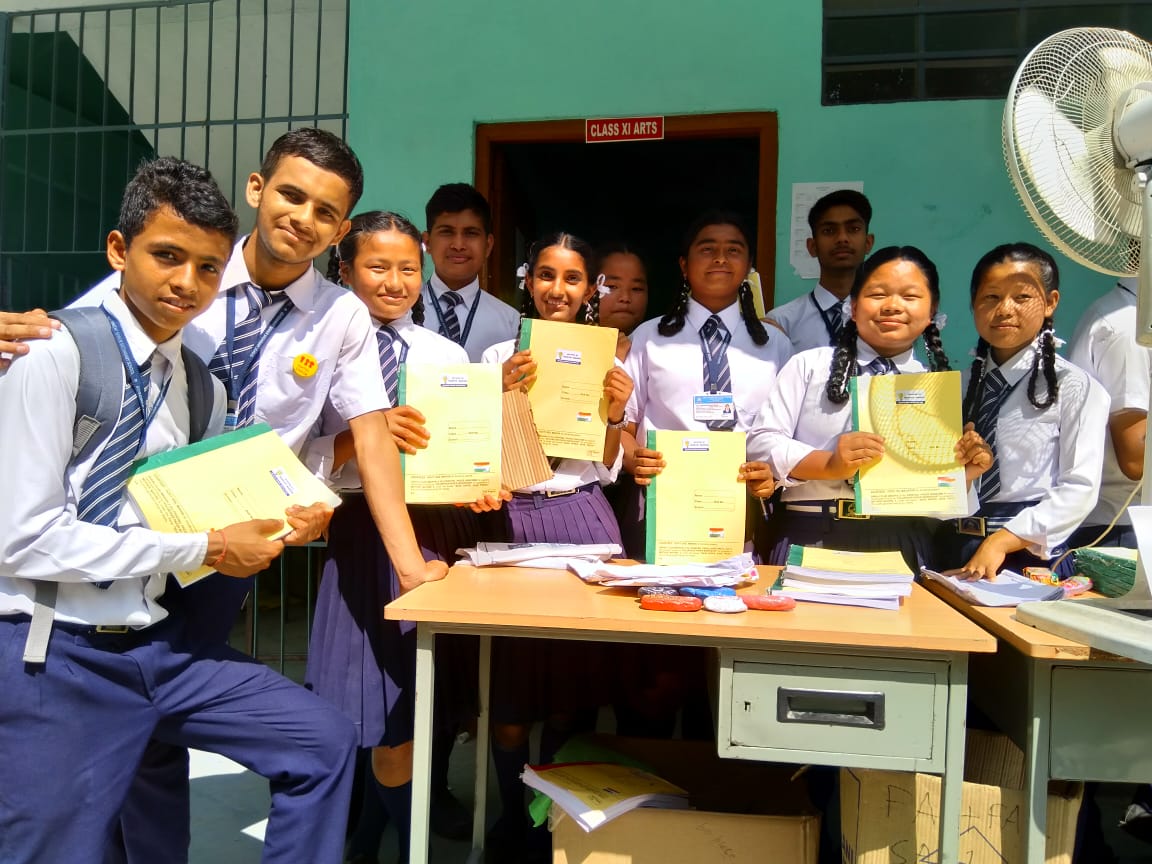

“Initially, the initiative wasn’t generating any interest. However, consistent efforts eventually led 20 schools to donate more than 30,000 waste pages by the end of that year. These were converted into 300 notebooks by 82 students in the first phase and 53 in the second. Each student had to spend 15 minutes every day on this project,” says Lomas.

For nearly every 100 books the school sold, the money collected helped sponsor one student’s education. Of course, not all that money came from sales—Lomas contributed half the amount.

However, thanks to these efforts, two female students were able to gain admission into the BA programme of IGNOU, Gangtok.

Besides papers, however, students also segregated the stapler pins attaching them together. “In total, we collected 10,000 pieces of stapler pins, which we sold to scrap vendors for recycling purposes,” he adds.

Also Read: Meet The Woman Whose Orchard Will Give Ladakh’s Stunning Handicrafts a New Home

His latest project, which he started last year, is called the Golden Rupee.

For Lomas, his battle against pollution isn’t all about generating alternative means of revenue, and the Golden Rupee initiative, he believes, is symbolic of this belief. For him, this is a civic duty.

So, what does this initiative entail?

Every three months, Lomas and his group of students collect dry waste from various households, including plastic, tin, glass (particularly bottles), and sell it to scrap dealers and recyclers for a grand total of Re 1 irrespective of the amount of waste collected.

Total amount scrap donated by school: More than 500 kg

No of ‘Golden Rupees’ earned: 4

“These initiatives are not only protecting the environment but also introducing a sense of civic study in the students, and helping them with their studies. The one condition I have set for students who want to join me in this work is that they must attend school and perform better in their academics. Many of them have taken up this challenge,” says Lomas.

Thanks to his initiatives picking up steam, Lomas receives invitations from various non-profits, hospitals, government offices and others to spread awareness about waste management.

His efforts are finally bearing fruit, and with the entire village community invested in his initiatives, Lomas is doing his part to make Makha better than he had found it.

What about you?

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167