Here’s How One Doctor-Turned-IPS Officer is Using Kindness to Counter Naxalism

In 2017, Dr Abhishek Pallava made headlines by treating a wounded Naxal. He now hopes his new initiative will change the lives of thousands in LWE affected Dantewada!

In March 2017, as additional SP of Bastar, Dr Abhishek Pallava made headlines for saving the life of a Maoist, Somaru, shot during an operation.

“Time was the key to saving his life as he was losing blood profusely and I being a trained doctor could not have looked the other way,” said Dr Pallava, in a conversation with Hindustan Times.

Earlier in January 2018, during a search operation to locate Pohru, the commander of a local Maoist unit with a Rs 3 lakh bounty on his head, Dr Pallava took the compassionate step of treating the fugitive’s ailing wife and malnourished children.

Suspecting that they were suffering from TB, Dr Pallava even managed to convince the family into getting treatment at the local district hospital.

Noble deeds for sure. So, it should come as no surprise that such thoughts, and actions, are part of a long string of efforts by Dr Pallava.

Here is an officer fully immersed into the area over which he holds jurisdiction. His wife treats patients in the local Dantewada district hospital, while his five-year-old son Avik, studies in a local school. One step after another, Dr Pallava is looking bring a healing touch to this strife-torn land.

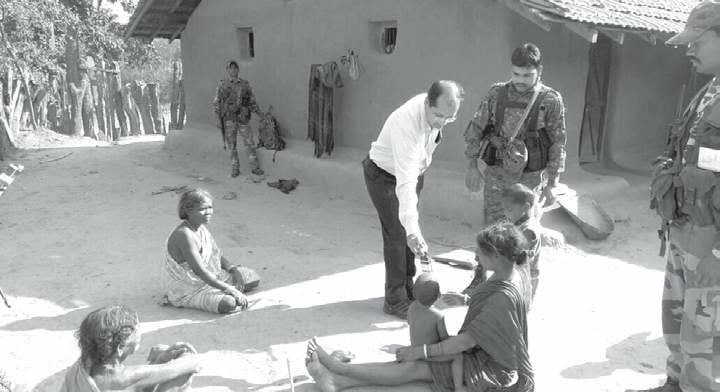

The Better India caught up with him to find out more about one such effort currently ongoing – medical camps.

Dr Pallava is a 2012-batch officer of the Indian Police Service – currently serving as the Superintendent of Police in the insurgency-affected Dantewada district in Chhattisgarh.

Alongside his official duties, since May 2016, Dr Pallava, a psychiatrist by training from the prestigious All India Institute Medical Sciences (AIIMS), has also been conducting health camps for locals residing in remote Naxal-affected villages of his district, alongside his wife Dr Yasha Pallava, a dermatologist.

“Over the past two and a half years, we have conducted 70-80 formal camps and about 100 small informal camps in remote areas where doctors are not available, health infrastructure is non-existent and areas where health workers do not wish to venture for fear of Naxals.

Both husband and wife treat small illnesses and offer necessary medication. They also impart information about the types of medication available, basic hygiene and address the problem of malnutrition by advising parents about the kind of food they and their children can consume.

People are screened for health issues and referred to either the district hospital in Dantewada or to the Apollo Hospital. Patients are transported to hospitals in police ambulances.

“We offer basic treatment and distribute government-supplied medicines from primary health centres (PHCs) depending on the specific ailment of a patient. For example, my wife is a dermatologist, and skin infections and allergies are pretty rampant in these parts, particularly in the local boarding schools,” he says, in a conversation with The Better India.

“We have treated 25,000 people over 2.5 years in Dantewada district, which has a population of just 2.5 lakh. Growing trust has resulted in locals coming into our district headquarters for various issues – like land agreements and even career counselling,” he says. And this was precisely the kind of effect the doctor couple was hoping to have.

“When we arrive at a village, we stay for six-eight hours. Initially, people are apprehensive and do not come for treatment out of fear. Within three or four hours, however, people start trickling in. Health is something everyone needs. So, if a child is sick, the parents would want him/her to get better. These initiatives break barriers between the police and locals,” says Dr Pallava.

These camps also act as a stress buster for police personnel – particularly the those in the lower rungs functioning in an intense environment.

“Their participation in these health camps also help the local population move away from stereotypes associated with us, and realise that these people are just like us and come from the same society,” says Dr Pallava.

The camps also help the police “establish contact with on-ground officials from other civil departments like health and education.”

On their return from these health camps, that information is relayed to the District Collector as feedback.

In districts like Bastar and Dantewada, where there have been multiple allegations of human rights abuses by the police and Central Reserve Police Force (CRPF), these health outreach camps also help counter Naxal propaganda.

“Treating locals’ spreads goodwill not only in the villages we visit but in nearby habitations as well. Earlier, very few people would come, but today in a village approximately 400-500 people turn up—a big deal in an area with very low population density. There is clear outline and plan in what we do,” he says.

“On certain occasions, we even take along local tribal faith healers, who help us communicate our message. We tell them that for small illnesses, they could approach a faith healer but for larger and more complicated ailments they need doctors.

This helps us to integrate the tribal community with modern medicine better. If we approach them directly, they will have suspicions. Yes, these medicines can have side effects, and thus we tell the local sarpanch or representatives to approach the nearest PHC, call us on our number or get in touch with the nearest doctor available for treatment,” he says.

Villages are chosen at short notice since they do not want to alert the Maoists – whose presence can create a security hazard for not just for the police, but the locals as well.

Particularly in Naxal-infested villages, there are fears among villagers that they could be targeted as ‘police informants’ if they accepted the medical treatment.

“If we don’t keep these things in mind, the consequences for villagers could be devastating. That’s why we keep local public representatives in the loop, who then convey to the Naxals that the police had arrived on their own accord and that no one brought them to this village,” he says.

More importantly, the police ensure not to collect any intelligence on Naxal-related activity during treatment. Any suspicion otherwise could have a detrimental effect on villagers.

“Intelligence will come by itself once there is trust, which in turn, assists our counter-insurgency efforts. If we ask them questions about Naxals in front of the village then their situation becomes dicey. Generally, we keep these two tasks separately,” he says.

‘Threat exists, but we have to do our job’

Venturing deep into Naxal territory comes with its own set of risks. Dr Pallava is no stranger to these them.

Just three months ago, a convoy of three journalists under the protection of seven police personnel came under attack from 150 Naxalites, despite assurances for their safe passage.

Dr Pallava and his team arrived onto the scene 15 minutes after the convoy came under the attack. The standoff lasted for around 45 minutes. Two policemen and one journalist tragically lost their lives.

“We waited for an ambulance. They were beyond our power to save,” he said, struggling to hold back tears in a video that went viral on social media.

“You can’t stop doing good things out of fear. We will have to take some calculated risks. More than police personnel, I often fear for the villagers over allegations of being police informers. They are often caught in the crossfire,” says Dr Pallava.

Having said that, the satisfaction of helping local tribal villagers often outweighs the risk, he adds.

“My father (a former Army officer) served in places like Assam and Nagaland. I’ve grown up seeing this kind of insurgency. With my training in psychology I believe that smart, intelligence-based, humane operations will get me better results,” he says.

“Some of my colleagues had told me nothing would come of these health camps. But each problem has its own peculiarities, and not all regions can adopt the Punjab model of policing you saw in the early 1990s,” he says.

“We need to change the stereotypes associated with the police. We need to be accountable to the public, even in Naxalite-affected areas. Whenever there are complaints of human rights abuses, we conduct a thorough enquiry within 24 hours. Such abuse complaints have come down in the last five years and the people share a better relationship with us today,” he says.

Also Read: Kerala Custodial Death Case: Here’s Why Capital Punishment For Cops is a Landmark

And his methods are paying off.

“Our soft approach has won over villagers in some parts. Naxals are scared that if they go to them, they’ll be caught,” he told The Print.

“They sense their end is near.”

(Edited by Vinayak Hegde)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167