‘Hostile’ Sentinelese? Here’s What The First Anthropologist to Meet Them Has to Say

Following a trail of foot marks, Pandit and his team walked one kilometre into the forest. But here's why they weren't attacked.

The death of John Allen Chau, a 26-year-old American evangelist, who was on a self-driven mission to spread Christianity in the isolated island of North Sentinel 700 miles off the Indian coast, has thrust the Sentinelese under an unwelcome spotlight.

Who are the Sentinelese?

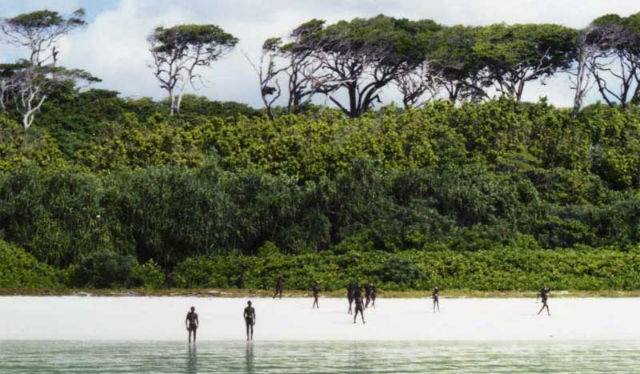

They are among the few remaining isolated tribes in the world. According to Survival International, a global organisation that champions the rights of tribal people around the world, “They are thought to be directly descended from the first human populations to emerge from Africa and have probably lived in the Andaman Islands for up to 60,000 years. The fact that their language is so different even from other Andaman islanders suggests that they have had little contact with other people for thousands of years.”

Chau’s death was deeply unfortunate. However, the notion of the Sentinelese being primitive people driven by an intense hostility of outsiders, so much so that they are hell-bent on killing them, is a patently false view, according to Trilok Nath Pandit.

Pandit is the first Indian anthropologist to successfully enter this isolated Andaman island back in 1967 along with a team of 20 members.

In a series of interactions with the press, Pandit has one permanent position on the Sentinelese—they want to be left alone—and in fact, expressed surprise at the killing of Chau.

“They are not hostile people. They warn; they don’t kill people, including outsiders. They don’t raid their neighbours. They only say, ‘leave us alone.’ They make it amply clear that outsiders are not welcome in their habitat. One needs to understand that language,” Pandit told Economic Times.

Pandit had first ventured onto the island in January 1967.

Posted with the Anthropological Survey of India in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands as its regional head, he led a team of 20 researchers, government officials and even Navy personnel, to explore North Sentinel, a 20 square-mile island, and develop contact with the tribesman there.

TN Pandit is among the leading authorities on the tribal communities living in the Andaman islands. Coming from a family of traditional scholars, Pandit initially had an interest in zoology, completing his BSc in the mid 1950s, before going onto studying cultural anthropology from the University of Delhi. Finishing his post-doctoral studies on a Government of India research, he took up a position on the faculty in the University of Delhi. In March 1966, he joined the Anthropological Survey of India, where he served for the 26 years before retiring towards the end of 1992. He also wrote an exhaustive account of the isolated tribes folk called The Sentinelese in 1990.

When Pnadit and his team first landed on the island, the Sentinelese hid behind the cover of the forest, silently observing these ‘aliens’ landing on their shores. There was none of that hostility, Pandit says. Following a trail of footmarks, Pandit and his team walked one kilometre into the forest and came across an open area consisting of 18 huts.

“Those (huts) were occupied, not abandoned, ones. I noticed a fire and cooked food items. We saw roasted fish, wild fruits. There were bows, arrows and spears all around. There were half-made baskets, too. They don’t wear any clothes. They don’t collect any stuff and keep it in their homes. But their houses are nicely built. Those were open lean-to huts made of tree branches and leaves with no doors or windows,” Pandit tells the Economic Times.

One of his team members did briefly see a Sentinelese tribesman, but there was no meeting and the entire hour spent on the island went off without incident. During subsequent visits, however, there was resistance. Before their boats could hit the shore, the Sentinelese would confront them with hostile gestures, bows and arrows.

Thus, these teams decided to maintain a safe distance and devised a strategy of dropping gifts like coconuts and utensils, among other things, before they hit the shore and then turn back.

In 1991, Pandit talked about how for the first time the Sentinelese came and collected gifts of coconuts from their hands in the water, but the teams were still not allowed to enter the island.

“They had decided that we weren’t dangerous, so they opened up to us a little. They also knew we had no intentions of staying on the island. Our languages might be different, but we understood them perfectly, they didn’t want us here,” Pandit tells The Print.

Estimates of the number of Sentinelese range from 15 to 500, but Pandit argues that 80 would be a more accurate figure.

It’s little surprise that these people harbour such hostility to outsiders considering its history. In the late 19th century, a British naval officer Maurice Vidal Portman landed on the island and kidnapped an elder couple, along with a few children.

He took them to his quarters on a nearby, yet bigger island, where the British ran a prison. The elder couple soon passed away, and it is unclear about what he did to the children. He soon returned them to the island and deemed his “experiment” a failure.

“We cannot be said to have done anything more than increase their general terror of, and hostility to, all comers,” Portman reportedly wrote in his 1899 book, describing this failure.

In other words, Chau’s evangelistic misadventure was only going to end in disaster going by the notings in his diary recovered by the international media.

Only if he had read Vidal’s writings.

“Two armed Sentinelese came rushing out yelling,” he wrote. “They had two arrows each, unstrung until they got closer. I hollered, ‘My name is John, I love you, and Jesus loves you.'” He goes onto write, “I felt some fear but mainly was disappointed. They didn’t accept me right away.”

Also Read: This Indian Island Is Home to the World’s Last Isolated Humans

Of course, what did he expect?

The news of his death was undoubtedly sad, but it’s a lesson to those seeking to forcibly interact with the Sentinelese without even a basic negotiation of terms with them along the lines of what Pandit and his team did.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra & Vinayak Hegde)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.