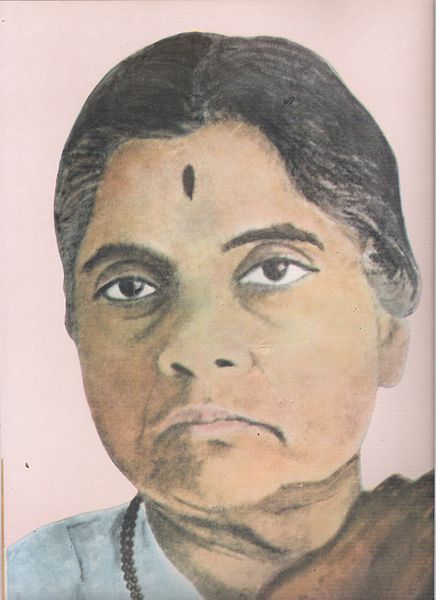

Durgabai Deshmukh: How a Child Bride From Andhra Became the ‘Mother of Social Work’!

Durgabai walked out of her own child marriage, helped draft the Constitution, set up key institutions and led the emancipation of women from the front.

There is no question that Durgabai Deskhmukh remains one of India’s most dynamic freedom fighters, a defender of social welfare and champion of women’s rights.

Married off at the age of eight to a wealthy zamindar, she had courage and wherewithal to successfully negotiate the terms of her withdrawal from that marriage at age 15 before the couple could consummate it; a decision supported by her father and brother. In ending her own child marriage, Durgabai set the tone for a life that would take her through the freedom struggle, drafting of the Indian Constitution, and a dogged battle for women’s emancipation.

Born on July 15, 1909, in the coastal Andhra Pradesh town of Rajahmundry to social worker BVN Rama Rao and his wife Krishnavenamma, Durgabai was raised in Kakinada. Despite the family’s limited means, the influence of her father’s spirit of selfless social service was evident. In her autobiography, ‘Chintaman and I,’ she describes a particularly poignant episode.

“Plague and cholera were prevalent those days. He was not afraid of helping those suffering from these dreaded diseases. He must have attended to hundreds of such victims. He used to take me with him on many of these occasions. Few would volunteer to carry the bodies of those who had died of plague or cholera, and ambulances were unknown. My father, along with three of his friends, used to be the pall-bearer. Though the streets of Kakinada were deserted, my father would take my mother and the two children — I had a younger brother, Narayana Rao — to the church, the mosque, or the burning ghat to show us how the bodies were disposed of, perhaps with a view to making us courageous enough to face the inevitable event of death,” she wrote.

She goes onto write about how her father’s “only mistake” was to marry her off as an eight-year-old.

Deeply influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, she soon immersed herself completely in the freedom struggle. When Gandhi was slated to visit Kakinada to address a town hall gathering in 1921, a 12-year-old Durgabai was determined to arrange a meeting between the great man and members of the local Devadasi and Muslim women community.

Those hosting the event demanded Rs 5,000 from Durgabai and her team of Devadasi-Muslim women, although she felt “they said this in a lighter vein, thinking that I would not be able to raise such a big amount”. The sum would be presented to him in pursuance of his struggles for freedom. Undeterred, she collected Rs 5000 with assistance from her Devadasi acquaintances, besides booking a venue for the meet despite the threat of arrest.

Following Gandhi’s visit, the entire family gave up all forms of Western wear and restricted themselves to only donning hand-spun Khadi. Additionally, Durgabai decided to quit school, arguing against the imposition of English. All this happened at the height of the Non-Cooperation Movement.

Nearly nine years later, she led the Salt Satyagraha movement in Madras after another freedom fighter, T Prakasam, was arrested by the British. However, she subsequently courted arrest and spent nearly three years (1930-33) in jail. In fact, she spent a year in solitary confinement.

Her time in prison would open her eyes to the circumstances under which many illiterate women were incarcerated for crimes they did not commit, but would confess to, due to the lack of access to education or a social network. This was the spark that inspired her not only to become a criminal lawyer in the future who would work pro bono but also take up numerous initiatives dedicated to the cause of women empowerment through education.

“I had then decided to take up the study of law so that I could give such women free legal aid and assist them to defend themselves,” she wrote in her autobiography following her incarceration, when she shifted focus from politics to her own education. Durgabai studied law, and in 1942, at the height of the Quit India Movement, she was accepted into the Madras Bar.

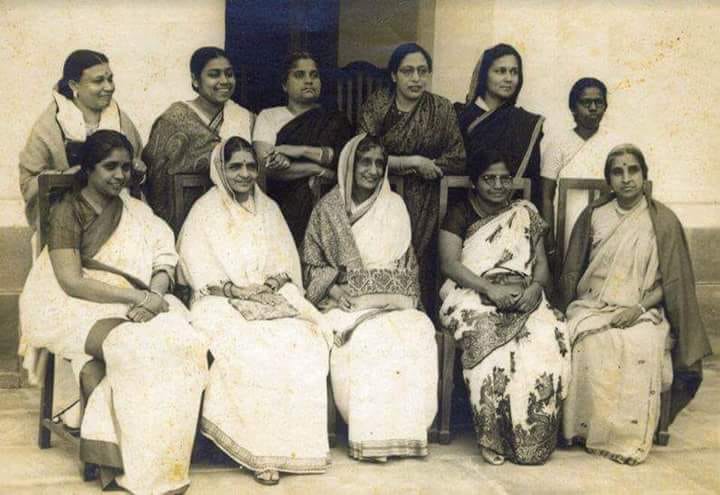

Around the same time, she also started an adult literacy programme for widowed, deserted or destitute women, helping them obtain their high school degree. As a consequence of such initiatives, she founded the now famous Andhra Mahila Sabha, a voluntary organisation for women that works across various fields, including health, disability, rehabilitation, legal aid and old age support among others.

Taking note of her extensive work in social service and her rising career as a criminal lawyer fighting for those wrongly convicted, she was inducted into the Constituent Assembly in 1946.

As a member of the Steering Committee, she actively participated in Constituent Assembly debates, fiercely defending property rights for women under the Hindu Code Bill, independence of the judiciary, selection of Hindustani (Hindi+Urdu) as the national language and for lowering the age bar for those seeking to hold seats in the subsequent council of states from 35 to 30.

On the subject of property rights for women under the Hindu Code Bill on April 8, 1948, she said, “The main argument in favour of limiting the estate in the case of women is that they are incapable of managing it and also that they are likely to be duped or exploited.

Also, it is said that they are illiterate and they do not understand the principles of management, and hence, there will be a strong inducement to designing male relatives to take away her right.

“My answer to all this is this. The house is aware that the daughter has an absolute estate in Bombay today. Therefore, on that ground, I do not think they are exposed to any risk. The other argument is that we have scores of instances where women have proved better managers than men,” she concluded.

Meanwhile, while presenting the case for an independent judiciary, she said, “The independence of the judiciary is a thing which has to be decided, and this independence to a large extent depends on the way in which these judges are to be appointed.

They should not be made to feel that they owe their appointment either to this person or that person or to this party or to that party,” she added. “They have to feel that they are independent.” Her words on the need for an independent judiciary have stood the test of time. Through her tenure in the Constituent Assembly, she reportedly moved 750 amendments alongside other members. Following Independence in 1950, she was inducted into the Planning Commission.

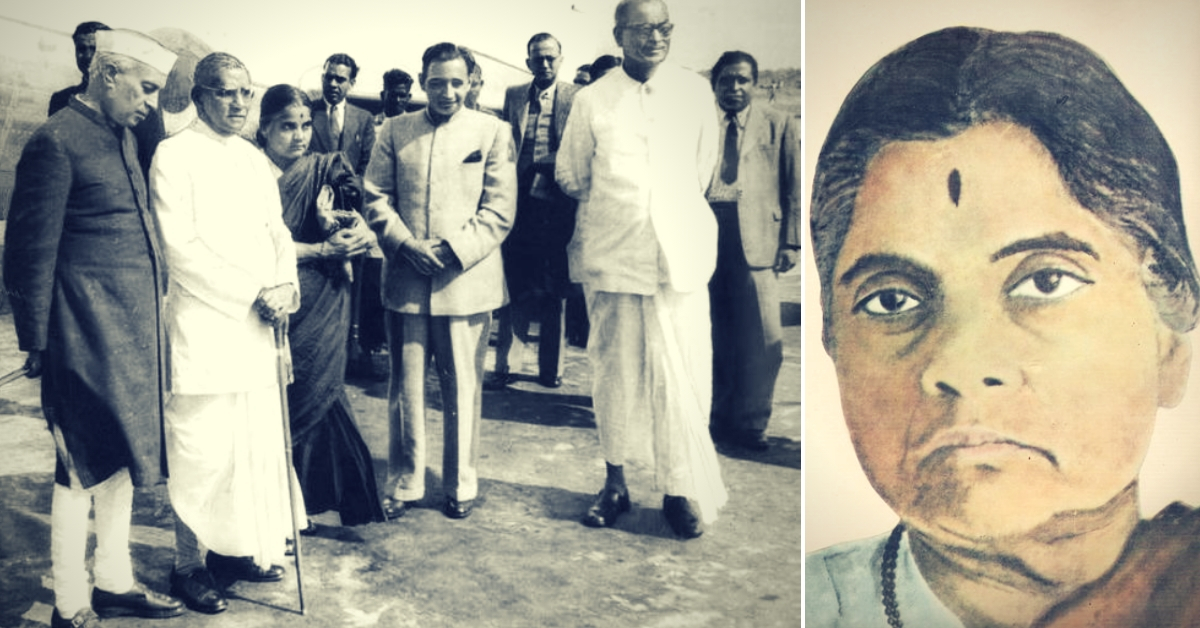

At the age of 44, she married her second husband, Chintan Deshmukh (the inspiration behind the title of her autobiography ‘Chintaman and I’), who was the first Indian to be appointed Governor of the Reserve Bank of India. At the time of their marriage, however, Chintaman was India’s Finance Minister. They had a civil marriage with India’s first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Sucheta Kriplani, India’s first woman Chief Minister, as witnesses.

They were a unique couple dedicated to the cause of nation building, and by some accounts, both Durgabai and Chintaman had decided, that if one of them, kept earning, the other would render their services to the country for free. Post-Independence, she dedicated her life to the law and social service. In fact, she is known as the ‘mother of social work’ in India due to her immense contribution.

Speaking to The Indian Express, Devaki Jain, an economist, said:

“As the first chairperson of the Central Social Welfare Board (CSWB), she set up things which are really enabling to women on the margins. Durgabai recognised that increasing welfare and better status for women would not be possible without budgetary provisions for them. At any time, the CSWB would be networked to more than 30,000 small NGOs, perhaps the biggest civil society network and all funded by the Government of India. They were organising Small Economic Programmes, and today we call them Self Help Groups.”

Interestingly, she was also one of the leading advocates for the establishment of family courts in India, an idea that emerged from her travels as a member of official Indian delegations to countries like China, Russia and Japan.

“I thought that for a country of India’s size, the establishment of family courts as part of its judicial system would be of immense help in many ways. It would not only reduce the workload of the High Courts and the Supreme Court but also provide a good forum for preventing family break-ups and restoring happiness to men, women, and children, making it possible for them to remain united,” she wrote in her autobiography.

The Parliament eventually enacted the Family Courts Act in 1984, setting up the institution three years after she had passed away on May 9, 1981.

Also Read: Warrior Begum of Awadh: The Untold Story of Hazrat Mahal’s War on the British

The legacy she leaves behind is of an institution builder, who selflessly worked towards the idea of an equal society where social and economic welfare would underpin development policy.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167