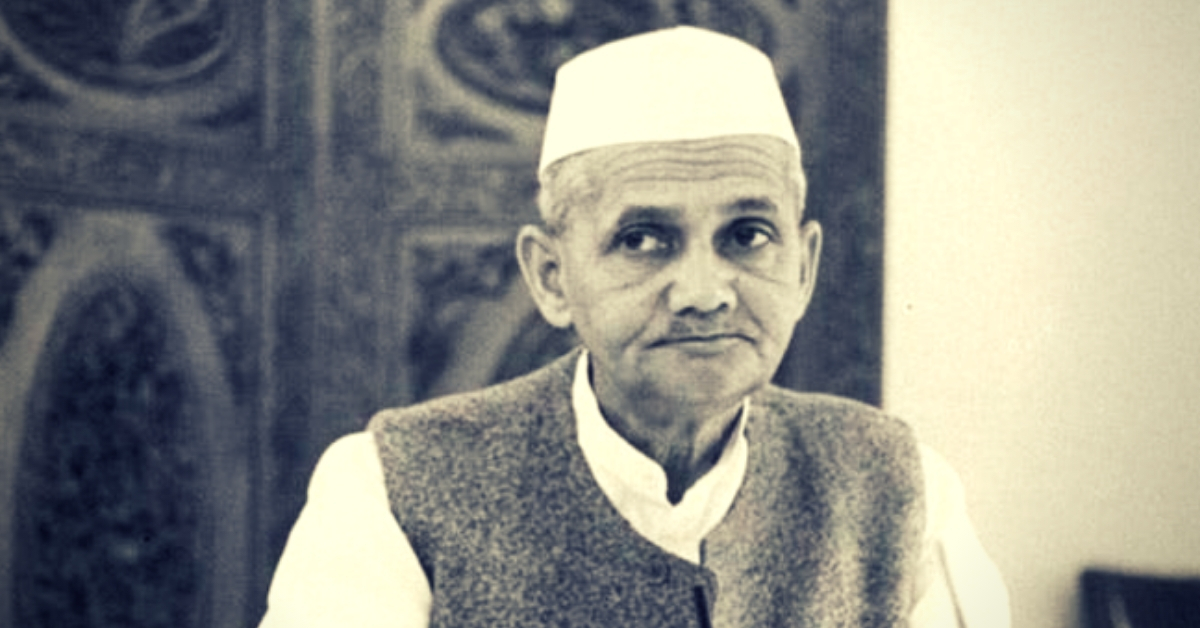

Lal Bahadur Shastri is India’s Original ‘Accidental Prime Minister’. Here’s Why!

Shastri's 18-month tenure showed the world that he was no puppet — he led India through what was probably its most difficult period in the Post-Independence era.

‘The Accidental Prime Minister,’ a feature film based on a tell-all memoir by Sanjay Baru, former prime minister Manmohan Singh’s chief spokesperson, is slated for release on December 21, 2018.

By most accounts, the film will present its version of events from Manmohan’s tenure as prime minister (2004-2014)—a period initially marked by high economic growth, which soon devolved into a slew of corruption scandals, instability and a naked power struggle within the coalition government. The accusation against Manmohan Singh was his inability to exercise real political power and that he was being propped up by former Congress president, Sonia Gandhi.

After his tenure ended in political disaster for the Congress, Manmohan came out saying that history will be kinder to him. Perhaps he was looking back at the life of Lal Bahadur Shastri while making this assertion, considering how the general political discourse in India no longer views the latter as the original ‘Accidental Prime Minister.’

Whenever Shastri’s name is brought up, many hark back to his famous ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan’ slogan, while forgetting that his rise to the top political office was facilitated by the political machinations of veteran Congress party leader K Kamaraj following the death Jawaharlal Nehru.

After 17 years of overseeing the growth of a nascent democracy, Nehru’s death had brought a great deal of uncertainty, and the world was looking at India for answers.

“The burning question is: How much was India’s devotion to democracy, to communal harmony and to nonalignment due solely to Jawaharlal Nehru? Not only the internal peace of India but the peace of Asia and perhaps of the world hangs on the answer,” said a New York Times op-ed dated June 3, 1964, a week after India’s first prime minister passed away.

Earlier that year, the NYT had written a short profile on the man they considered as the “chosen successor of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru.”

Described as a “colourless, self-effacing, teetotaling, vegetarian peacemaker,” the profile on Lal Bahadur Shastri is largely positive—there is even a reference to his sense of personal responsibility in resigning as Minister of Railways and Transport following a disastrous railway accident for which he took the blame personally.

The NYT profile was prescient in describing Shastri’s acceptability across all ideological factions of the Congress party. With the spirit of the freedom coursing through his veins, after spending nearly a decade in prison, giving up formal education to attend a nationalist college, following Mahatma Gandhi into a battle of passive resistance against the British and becoming a loyal soldier for Nehru post-Independence, Shastri was a highly respected figure.

“Mr Shastri is known as one of the most adroit among Indian politicians at not making enemies. His solid reputation in the ruling Congress party is based on his services as an arbitrator and a conciliator among innumerable rivalries and feuding personalities. Politically Mr Shastri is known as a man of the centre, who moves with ease and apparent impartiality among almost all the diverse elements of Indian political life,” wrote the American publication.

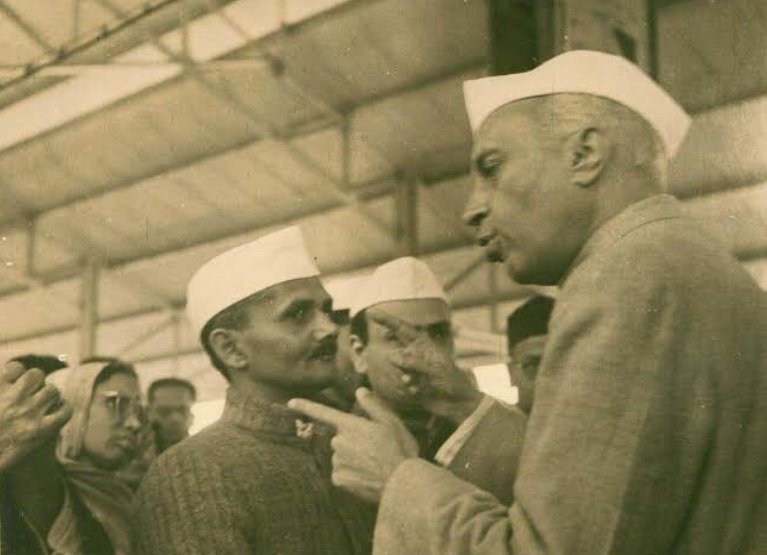

However, Nehru had not anointed a successor before his death, and the battle for supremacy was on with Kamaraj pulling the strings under his famous “Kamaraj Plan” to reinvigorate the party.

With Moraji Desai as the senior-most leader in the party, there was an assumption that he would take over the reins but his “trademark obstinacy” wasn’t very appealing to vast sections of the party. In his book ‘Succession in India’ (1966), author and journalist Michael Brecher narrates how Kamaraj and his allies in the party sought to supplant Desai’s bid and “support the man who was least likely to divide and most likely to unite the party.”

Nonetheless, Kamaraj and his team had to navigate a real power struggle in the week following Nehru’s death with many senior leaders throwing their hat in the ring for the top job stitching up alliances on regional and caste considerations. However, there were two who stood above the rest—Gulzarilal Nanda, caretaker PM, and Moraji Desai, who declared his candidacy a mere day after Nehru’s death, a move which many had thought showed no tact.

Despite the lobbying, leaders like Nanda and Defence Minister Yashwantrao Chavan knew that the world’s eyes were upon India and whether this nascent democracy could transition from Nehru and keep his vision alive. Even though Nanda had thrown his hat in the ring, he was “conscious that the world’s eyes were upon us, and we did not want to display too open a fight.”

Kamaraj, meanwhile, was “consulting” hundreds of Congress parliamentarians and attempting to create a “consensus” around Shastri. As Nehru’s trusted lieutenant VK Krishna Menon once said, this wasn’t really a consultation. “When the Congress president calls you unless you are a fool like me, you more or less express his opinion,” he said. Soon, Shastri became the party’s “official” choice for prime minister, and the likes of Nanda and Desai had to withdraw.

India’s second PM, who himself had made no claim for the top job, took over the reins of this country at a very critical juncture, and as historian Manu S Pillai argues in this article, “a man who in 18 months made a mark not as a puppet, but a leader worthy of respect and admiration.”

In his first broadcast as Prime Minister on June 11, 1964, Shashtri said:

“There comes a time in the life of every nation when it stands at the crossroads of history and must choose which way to go. But for us, there need be no difficulty or hesitation, no looking to right or left. Our way is straight and clear—the building up of a secular mixed-economy democracy at home with freedom and prosperity, and the maintenance of world peace and friendship with select nations.”

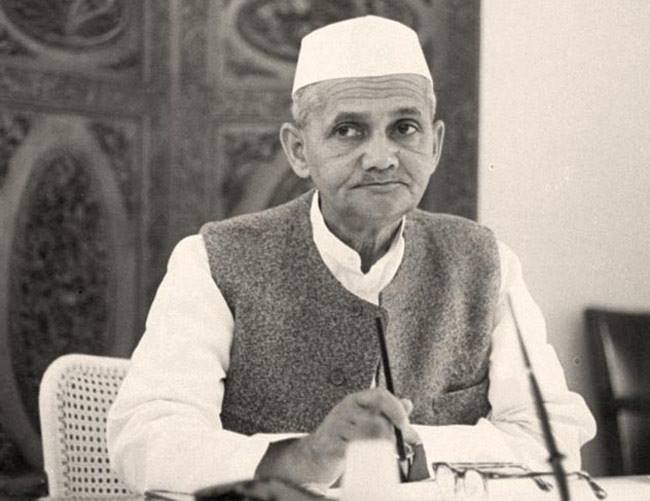

His 18-month tenure as prime minister was extremely eventful. Showing real leadership, he helped India navigate through probably its most crisis-ridden period.

From calming the violent anti-Hindi agitation that erupted across the southern states to taking the first steps in resolving India’s biggest food shortage by promoting the Green Revolution (and convincing people to voluntarily give up one meal so that the food saved could be distributed to the affected populace) and the White Revolution (Amul cooperative), Shastri also oversaw India’s first major shift away from Nehru’s socialist economic policies based on central planning.

However, his crowning moment was leading India in the 1965 war against Pakistan, delivering probably one of the most iconic slogans of Independent India, ‘Jai Jawan, Jai Kisan.’

“In the utilization of our limited resources, we have always given primacy to plans and projects for economic development. It would, therefore, be obvious for anyone who is prepared to look at things objectively that India can have no possible interest in provoking border incidents or in building up an atmosphere of strife… In these circumstances, the duty of Government is quite clear, and this duty will be discharged fully and effectively… We would prefer to live in poverty for as long as necessary, but we shall not allow our freedom to be subverted,” he told the Lok Sabha prior to the war, which officially began in the first week of August 1965, before an UN-mandated ceasefire brought it to an end on September 23, 1965.

Following the war, Lal Bahadur Shastri and his Pakistani counterpart General Ayub Khan signed the Tashkent Declaration on January 10, 1966, bringing all hostilities to an end for the being, although back home it was criticised for not compelling Pakistan into agreeing to stop all attempts in fomenting discontent in Kashmir.

Shastri died in Tashkent after signing the agreement, reportedly due to a heart attack, but many believe that there was a conspiracy behind his death.

Also Read: CN Annadurai: Karunanidhi’s Mentor & Tamil Nadu’s First Political Stalwart

In his book, Patriots and Partisans, noted historian Ramachandra Guha, presents a scenario had Shastri not tragically passed away.

“Had Shastri continued as prime minister until the end of the 1960s, the economic history of India would have turned out very differently. In the 1950s, under the direction of the state, India had nurtured a robust domestic industry. It was now time to allow for the free play of market forces.

In speeches made in 1965, Shastri clearly indicated that he would like to open up the market to enterprise and free competition. Sadly, he died soon afterwards. Instead of trusting to the energy of the private sector, Indira Gandhi strengthened the control of the state over the economy.

Had fate given Shastri longer innings as prime minister, the Indian economy could have been more robust and resilient, but he was also a pragmatic reformer.

He would have freed the processes of production from state control and also initiated welfare measures to ameliorate poverty. As a man of vision and integrity, he would have also sought to improve the performance of India’s public institutions.

Had Shastri lived for another five or ten years it is highly unlikely that Indira Gandhi would ever have become prime minister and it is certain that her son would have never occupied that office.

Had Shastri been given another five years on earth, there would have been no Nehru-Gandhi dynasty. Had Shastri lived another five years, Sanjay Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi would almost certainly have been still alive. Sanjay Gandhi would have been a failed entrepreneur and Rajiv Gandhi, a recently retired airline pilot with a passion for photography.

Finally, had Shastri live another five years, Sonia Gandhi would still be a devoted and loving housewife and Rahul Gandhi, a middle-level manager in a private sector company.”

Following this passage, it’s fair to suggest that had Shastri lived for another five to ten years, Sonia Gandhi may not have taken over the reins, leaving Manmohan Singh to his academic pursuits.

Yes, both Manmohan and Lal Bahadur Shastri were ‘Accidental Prime Ministers’ and reformists in their own right, but one took the opportunity to establish himself as a leader with moral courage, while the other dithered at critical junctures. Maybe history will be kinder to Manmohan, but Shastri requires no such kindness. The only question history would pose to us is ‘What if Shastri lived on?’

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167