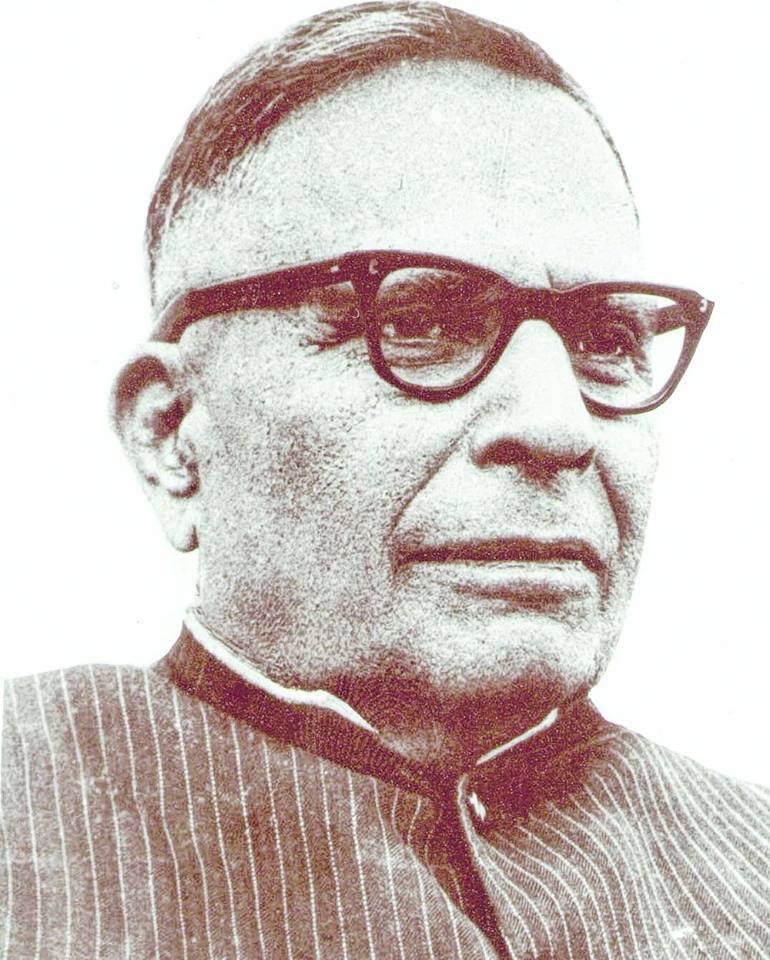

How This ‘Lion of Odisha’ Took On the British & Helped Sardar Patel Unify India!

From breaking barriers of untouchability to building modern-day Odisha, Harekrushna Mahatab left behind a truly remarkable legacy. Yet few Indians know about this freedom fighter. It's time this changed. #ForgottenHeroes

To honour this nation’s Independence Day, we bring you the fascinating stories of #ForgottenHeroes of #IndianIndependence that were lost among the pages of history.

Mainstream media in India has done a shoddy job in its coverage of Odisha. Like Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, the Northeast and the other frontier regions of this country, the state usually appears in the mainstream national consciousness only if there are major elections, a natural disaster, a Maoist attack, or a gut-wrenching tales of poverty.

Is it any surprise that many of you know little about Harekrushna Mahatab, the architect of modern-day Odisha (and its first chief minister), freedom fighter, social reformer, literary figure, Gandhian and the man who kick-started the delicate process of merging princely states into the Indian Union?

As a major figure of the Indian National Congress, he was also a minister in India’s first Union cabinet and a member of the Constituent Assembly.

Born on November 21, 1899, in the Agarapara village of the state formerly known as Orissa’s Balasore district, Mahatab came from an aristocratic Khandayat family. Finishing his matriculation from Bhadrak High School, one of the state’s oldest schools, he enrolled into Ravenshaw College in Cuttack.

However, Mahatab’s time in college came to a premature end after he joined the Indian National Congress. His time as an observer of the 1920 Calcutta and Nagpur sessions of the INC left an indelible mark on him, and inspired by the likes of Mahatma Gandhi, Mahatab joined the movement for Independence starting off with the Non-Cooperation Movement.

During his early days in the freedom struggle, he served as secretary of the Balasore District Congress Committee, coordinating the boycott of foreign made clothes and products—one of the defining features of the Non-Cooperation Movement. He was imprisoned and charged with sedition for his troubles. Nearly a decade later in 1930, he was elected president of the Utkal Pradesh Congress Committee, where he directly oversaw the party’s operations.

Driven by Mahatma Gandhi’s famous Dandi March, an act of nonviolent civil disobedience in colonial India to produce salt from the seawater in Gujarat, Mahatab oversaw the successful salt satyagraha in Orissa.

Initially, local Congress leaders were apprehensive about how they would carry out their foot march from the Swarajya Ashram of Cuttack towards Inchudi to break the British salt laws, but alongside Pranakrushna Padhiary, Mahatab convinced the local leadership that this act of protest was feasible.

Eventually, the local Congress leadership led by fellow freedom fighters Gopabandhi Chaudhury and Acharya Harihar Das, along with 21 other satyagrahis, proceeded to break the British salt laws. He was imprisoned but released from prison in July 1932.

In 1923, and with the purpose of spreading the gospel of freedom and democracy, he successfully started a weekly named ‘Prajatantra,’ which went onto become a full-fledged daily newspaper in 1930. Although its publication was suspended in 1932 following coercive action by the British colonialist, it reappeared on the eve of Independence. The newspaper remains in circulation even today. He also edited the ‘Jhankar’ monthly since its inception, founded the ‘Prajatantra Sudhar Samiti’ and remained dedicated to this noble task well after retiring from politics in 1977.

Elected General Officer Commanding of Congress Seva Dal (INC’s grassroots fronts organisation) the same year during the 1932 Puri session of the INC, Mahatab led a major social reform movement against untouchability. Inspired by Gandhi, he sought to bring them into the mainstream.

“He visited many areas of the district and organised meetings on the issue. In a meeting at Bhadrak, he advocated the idea of allowing the ‘depressed classes’ to the inner shrines.

During October (1932), Mahatab led a group of outcasts to his family temple in Agarpara and made them touch idols, for which, of course, his family suffered social boycott by the orthodox Hindu elements. Under his initiative, a night school for the outcasts came into function in Bonth area,” says this biography by Professor MN Das and Dr CP Nanda.

Impressed by his revolutionary zeal and work, the then INC president Subhash Chandra Bose nominated him to the Congress Working Committee in 1938 and stayed a member till 1950.

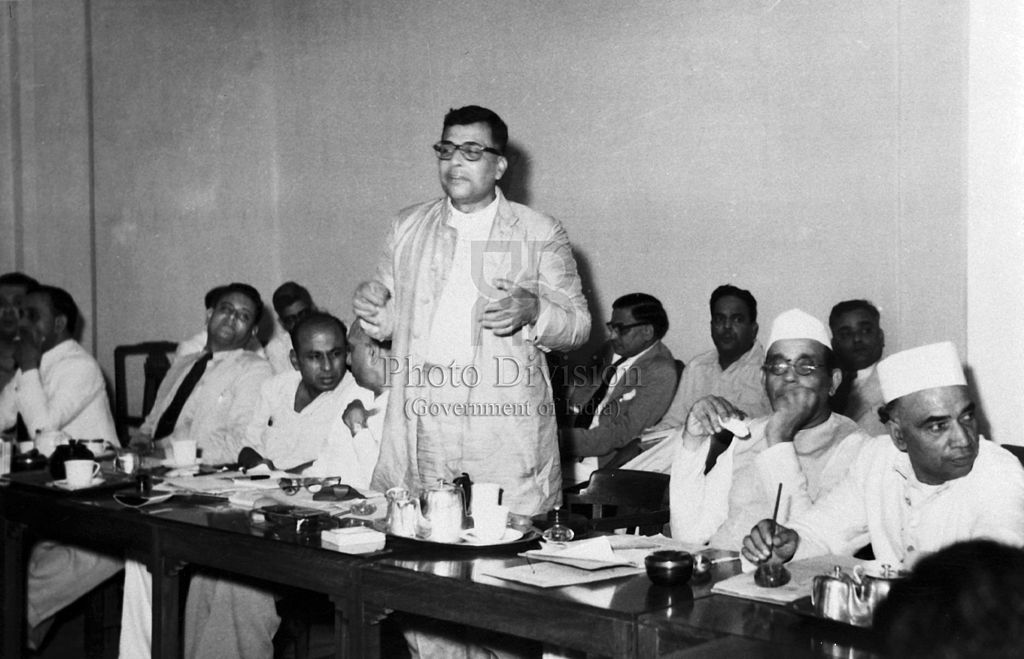

It is during this period when his position on princely states, which would have significant implications, later on, came to fruition. As President of State People’s Enquire Committee, he recommended the withdrawal of state support for erstwhile princely states and their merger with Odisha Province, besides leading a people’s movement to achieve the same.

He subsequently joined the Quit India Movement, and along with major INC bigwigs like Jawaharlal Nehru and Abdul Kalam Azad, he was arrested. He spent more than two years in the Ahmednagar Fort Jail before his release in May 1945.

During his final stint in prison, he wrote a novel ‘Nutan Dharma,’ a play ‘Swarajya Sadhana’ and a book on the complete History of Orissa, besides continuing to write for Prajatantra. Among other things, he also started a weekly journal called ‘Rachana’ inspired by Gandhi’s weekly publication Harijan. The objective here was to disseminate Gandhian thought.

His most critical contribution to Independent India was his work in merging the 26 Oriya speaking princely states with the Indian Union, a process which began in 1946 when elections for the provincial Legislative Assemblies were held under the aegis of the British colonialists.

Elected as the Chief Minister of Orissa on April 23, 1946, he issued two notification to all the princely states seeking their cooperation for a merger.

“So far as Orissa is concerned, considering its geographical, linguistic and ethnological affinity with the states, it is desirable that there should be one administration for both the states and the province; otherwise both the province and the states can have no efficient planning in the absence of which each part will be weak in comparison with the other states of India,” he said in a meeting with the rules of the respective princely states on October 16, 1946.

Little surprise, the monarchs were not thrilled with the idea of a merger with Orissa, and they set up the Eastern State Federation under the aegis of the Maharaja of Patna.

The federation didn’t last too long, with demands for accession to Orissa province starting in the erstwhile princely state of Nilgiri. The local Maharaja responded to these demands with brutal force, but the local freedom fighters fought back. When constitutional methods bore little fruit, Mahatab sought military assistance from the interim Indian government.

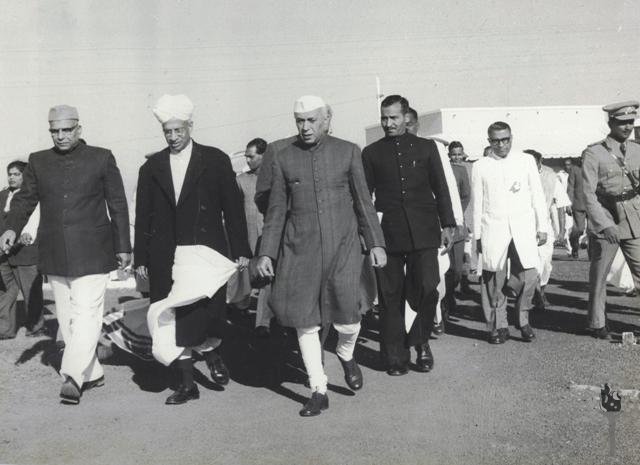

Home Minister Sardar Patel, who was the chief architect of merging the princely states into the Indian Union, agreed and authorised the Orissa government to take over Nilgiri. However, Patel warned Mahatab that any failure in fulfilling this merger would be on him. Fortunately, the takeover was complete by November 14, 1947, with minimal bloodshed.

This incident further motivated Mahatab to pursue this process of establishing the contours of modern-day Odisha, and eventually India.

Challenging civil servant VP Menon, a central figure in the merger process, Mahatab argued against any attempt to allow princes any degree of administrative powers—a suggestion Patel agreed to. In fact, Mahatab was also instrumental in bringing Patel to meet the rulers of various princely states and persuade them of accession.

“If you do not accept our proposal (for a merger) I don’t take responsibility for law and order in your state. You take care of that yourself,” Patel reportedly told rulers in a meeting. With local groups comprising of key figures in the freedom movement ready to overthrow these rulers, the erstwhile princely states had little choice but to acquiesce. This is what kick-started the merger process.

During his tenure as chief minister, he was also instrumental in shifting the state capital from Cuttack to Bhubaneshwar and the sanction and construction of the multi-purpose Hirakud Dam Project.

Eventually, Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, invited Harekrushna Mahatab to become his Union Minister for Industry and Commerce in 1950. It was an odd choice since his economic views were in direct contrast to Nehru’s.

As a staunch Gandhian, he wasn’t big on central planning and believed that every Indian village could be converted into a little self-sufficient republic.

“After Patel’s death, differences—over foreign aid and abolition of the privy purses of the rulers—started to arise between Nehru and Mahatab and he was dropped from the next cabinet.

Mahatab was not an enthusiastic supporter of American aid and wanted its usage to remain restricted to capital projects like industries. He didn’t want any aid to be used for community projects as he believed that it would initiate a propaganda war between the Americans and the Soviets in India’s hinterland.

Also, Mahatab wanted the privy purses of rulers scrapped while Nehru felt that the government could not so easily renege on its commitments,” writes Achyut Mishra for The Print.

Despite leaving the cabinet, he remained very active in politics, serving as Governor of Bombay in 1955-56 and earning a second run as chief minister of Orissa from 1956 to 1960.

During his tenure as chief minister, he was also instrumental in establishing the famous Rourkela steel plant, Utkal University in Bhubaneshwar, Odisha High Court and the Cuttack Wireless station. Elected to the Lok Sabha in 1962 from Angul Constituency, he also served as vice president of the INC in 1966. However, turmoil in the party following Lal Bahadur Shastri’s untimely demise, its move to the political left under Indira Gandhi and general disenchantment with the party drove Mahatab to leave the INC the same year.

Also Read: Martyred at 26, This Naga Freedom Fighter Has a Story Every Indian Must Know

He went onto establish the Orissa Jana Congress and elected three consecutive times starting in 1967 to the state assembly. The Orissa Jana Congress and Swantantra Party formed a coalition government in 1967 to upset the INC, although it lasted only two years.

Harekrushna Mahatab was also among veteran freedom fighters who were also sent to prison during Emergency, as he challenged the Indira Gandhi regime. After a string of failures, the Orissa Jana Congress merged with the Janata Party in 1977.

Aside from his politics, Mahatab was a prolific literary figure as well. In fact, he won the Sahitya Academy Award in 1983 for his famous three-volume work, Gaon Majlis, in Odia. He retired from active politics after the end of Emergency in 1977, and passed away a decade later on January 2.

There is a lot more to Mahatab’s life, and this piece just skims the surface on the life of a remarkable figure. It’s safe to assume that poor mainstream coverage media of Odisha has meant ignorance of some of its most prominent figures. Starting with Harekrushna Mahatab, it’s time to change that.

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167