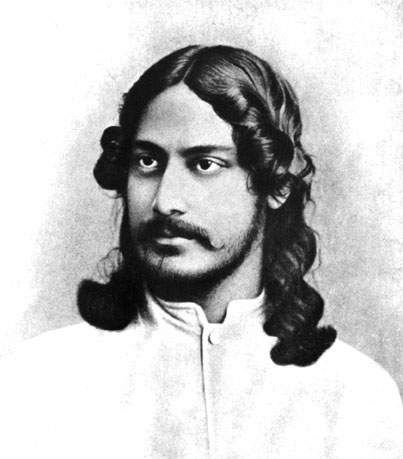

Death, Grief, Wanderlust and Love : How Rabindranath Became ‘Gurudev Tagore’

Tagore was 14 when his mother, Sharada Devi, passed away. Later in life he had to encounter the death of many loved ones, one after another.

“I know not who paints the pictures on memory’s canvas; but whoever he may be, what he is painting are pictures; by which I mean that he is not there with his brush simply to make a faithful copy of all that is happening. He takes in and leaves out according to his taste. He makes many a big thing small and small thing big. He has no compunction in putting into the background that which was to the fore, or bringing to the front that which was behind. In short, he is painting pictures, and not writing history.”

These lines are from ‘Jiban Smriti’ (My Reminiscences), Rabindranath Tagore’s autobiography, which he wrote when he was only 50 years old.

Tagore, who was also known as ‘Gurudev,’ was born on 7 May 1861 in Jorasanko Thakur Bari, the ancestral home of the Tagore’s, in Kolkata, which was then known as Calcutta and was the capital of British India.

As a child, he was left in the care of cooks and maids, except on Sunday mornings when his mother would make him take a bath with the homemade fairness scrubs.

Even though he grew up in a large family, alongside his siblings and many cousins, he would spend most of his time alone, which made him a loner and an introvert. However, this gave his mind a fair chance to fly the wings of his imagination.

This also led him to notice the minute details of nature which inspired him to turn to poetry. As he recalls his first poem was—

“Brishti Pode, Paata node..” (The rain patters, the leaf quivers)

His first step at Shanti Niketan

PHOTO SOURCE

In February 1873 after his upanayan (coming-of-age) rite at the age of eleven, Tagore and his father left Calcutta to tour India for several months.

This tour was when Tagore visited ‘Shanti Niketan,’ his father’s estate, for the first time. Little did he know that this place was going to be associated with his name forever.

“I was never tired of roaming about among those miniature hills and dales in hopes of lighting on something never known before. I was the Livingstone of this undiscovered land which looked as if seen through the wrong end of a telescope. Everything there, the dwarf date palms, the scrubby wild plums and the stunted jambolans, was in keeping with the miniature mountain ranges, the little rivulet and the tiny fish I had discovered.”

Tagore’s first encounter with death

Tagore was 14 when his mother, Sharada Devi, passed away. Later in life he had to encounter the death of many loved ones, one after another—his sister-in-law Kadambari Devi, who was a dear friend and a significant influence, his wife Mrinalini Devi, his daughters Madhurilata and Renuka, and his son, Shamindranath.

“Jibono Moroner Shimana Chadaye…Bondhu he aamaar royecho dadaye…”

(Beyond the bounds of life and death,

There you stand, Oh! my friend)

After his mother’s demise, Tagore mostly avoided classroom schooling and preferred to roam the manor or the nearby areas of Bolpur and Panihati. He loved to spend time walking and connecting with nature, and this was perhaps the reason why he eventually set up an open school many years later, to emphasize the joy of learning in a natural environment.

Poetry to the rescue

Photo Source

At the age of sixteen, Tagore wrote—

“… It was a cloudy afternoon, rejoicing with the overcast interval I eased on the bed with my face down and wrote a couple of words on a slate –

Gahan kusumakunja-maajhe

It was a kind of euphoria I felt after that.”

Tagore immersed himself into writing to forget everything else and feel this joy again and again, but his father wanted him to become a barrister, and he was soon sent to England to study law. However, Tagore’s poetic mind could not grasp the ifs and buts of law, and he returned home without a degree.

He shared this love for literature with his sister in law, Kadambari Devi, and the two became close friends.

However, tragedy struck for the second time when Kadambari committed suicide on 21 April 1884, just four months after he married Mrinalini Devi, and he was left devastated. His novella ‘Nastanirh’ (The Broken Nest) is believed to be the story of Kadambari Devi.

To busy his mind and help him come out of the grief, his father ordered him to visit Shelaidaha (today, a region in Bangladesh) and manage the family’s vast ancestral estates. For the first time, Tagore experienced the real world and came in touch with people who were struggling to live but were content with whatever they had.

“I am a townsman, city born… it was the first experience of village life for one who had remained from childhood inside his city residence.”

Chhinnapatra

Photo Source

Although this new experience helped him get over the intense grief of losing his friend, Tagore longed for a companion who would share his interests, and he found one in his well-read and well-educated niece, Indira Devi. Between 1889 and 1895 he wrote almost 250 letters to her and bared his sensitive soul.

These letters are more than letters. They are a sort of diary and reveal intimate details of his daily life, experiences and sensibilities. Fortunately, the letters were not lost, because Indira had copied them all in two notebooks and were eventually published as ‘Chhinnapatra’ (Torn Letters).

The letters give us a glimpse of Tagore’s growth as an artist. He writes of experiencing the beautiful river by whose bank, and in a boat, he spent hours on end, alone, steeped in the beauty of nature, and wrote ‘Sonar Tori’ (The Golden Boat) during this time.

He met several bauls and boatmen, who inspired him to compose some of his most famous songs—their influence is perceptible in both music and philosophy.

The next ten years are considered to be the most productive period of Tagore’s literary career. At this time he also started writing short stories (later collected in Golpoguchha) and created a new genre in Bengali literature.

Patriotism

Photo Source

In real time, however, the country was in turmoil. Protests against British imperialism had begun. While Tagore was a massive supporter of Indian nationalists and wanted to serve the cause, violence was something he abhorred.

Tagore returned to Bolpur and started his dream school ‘Bolpur Brahmacharya Vidyalay,’ an open school on the lines of a ‘Gurukul’ which was drastically different from the British model of education being forced upon Indians, which he believed only created a pool of obedient clerks.

The British government passed the orders for the partition of Bengal in July 1905, which came into effect on October 16 of the same year. However, the date fell in the month of Shravan, when the festival of Raksha Bandhan is celebrated by the Hindu community.

Following Tagore’s call, hundreds of Hindus and Muslims in Kolkata, Dhaka and Sylhet came out in large numbers to tie Rakhi threads as a symbol of unity. The decision to partition Bengal was withdrawn in 1911, after six years of widespread protest by both the communities from West and East Bengal. Tagore wrote around two dozen patriotic songs at this time.

Grief

Photo Source

Tagore’s personal struggles continued. In 1902, he lost both his wife and daughter, Renuka. His father passed away in January 1905, and in 1907, on the fifth death anniversary of his wife, his son Shamindranath died of cholera at the age of 11.

“When his last moment was about to come I was sitting alone in the dark in an adjoining room, praying intently for his passing away to his next stage of existence in perfect peace and well-being. At a particular point of time my mind seemed to float in a sky where there was neither darkness nor light, but a profound depth of calm, a boundless sea of consciousness without a ripple or murmur. I saw the vision of my son lying in the heart of the Infinite and I was about to cry to my friend, who was nursing the boy in the next room, that the child was safe, that he had found his liberation. I felt like a father who had sent his son across the sea, relieved to learn of his safe arrival and success in finding his place. I felt at once that the physical nearness of our dear ones to ourselves is not the final meaning of their protection. It is merely a means of satisfaction to our own selves and not necessarily the best that could be wished for them.”

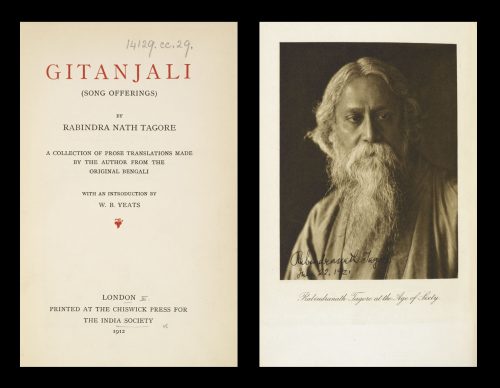

The Nobel Prize

Photo Source

In March 1912, a severely ill Tagore returned to Kuthi Bari, a house built by his grandfather in Shilaidaha. He was too weak to write anything new, but couldn’t sit idle either, so he started to translate his own work ‘Gitanjali’ into English.

A year later, on a November evening, a telegram that had been redirected from Jorasanko (his Calcutta address), arrived at Shantiniketan.

He had won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and the news had travelled all the way from Sweden to the dusty village roads of Bolpur. However, Tagore remained stoic, and handed over the telegram to a colleague at Shanti Niketan and said, in jest—

“Here comes the money for your sewage system.”

He knew how fickle joy and fame could be…

(Edited by Gayatri Mishra)

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected]

Connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let's ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167