Periyar, The Firebrand Pioneer Who Shaped The Dravidian Revolution

A feminist, an egalitarian and a true social activist, the legend etched his mark on public discourse about women’s rights, rationalism, and caste.

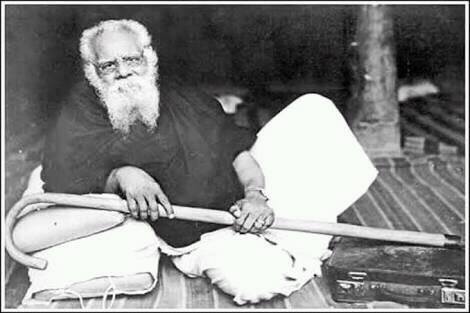

Born on September 17, 1879, in the city of Erode, Tamil Nadu, Erode Venkata Ramasamy Naicker, popularly known by his followers as Periyar (‘elder or wise one’) or Thanthai Periyar, was a radical social reformer.

Popularly known for extensively speaking out and fighting against the evils of caste discrimination with his famous Self Respect Movement, he also espoused rationalism and women’s rights—ideas that were way ahead of their times.

In a public life spanning over 70 years, it is nearly impossible to encapsulate in a few hundred words why Periyar is still held in such high regard, especially among the Tamils.

His pilgrimage to the holy Hindu town of Kashi in 1904 to visit the Shiva temple of Kashi Vishwanath is a good place to start. His experiences during this pilgrimage profoundly shaped his politics.

His disgust at the sight of prostitution, cheating, looting, floating dead bodies and rampant begging on the streets of Kashi conflicted with the romantic notions that many had held of this holy town.

There was one particular incident, however, which scarred him for life.

At the choultries (resting places) adjoining the temple, free food was on offer to Brahmin pilgrims. When Ramasamy stood in line to partake of these meals, he was refused because of his caste.

One day, out of desperate hunger, he decided to go in disguised as a Brahmin, wearing the sacred thread. Unfortunately, his moustache gave away his identity since temple authorities believed that holy texts did not permit Brahmins to have moustaches. He was denied food and pushed out into the streets.

Afflicted by unbearable pangs of hunger, Ramasamy had no choice but to eat the leftovers thrown into the streets. He realised, in shock, that the choultry which had refused him entry was built by a wealthy non-Brahmin merchant from Tamil Nadu!

“Why and how can Brahmins obstruct Dravidians from taking meals in the choultry, although the choultry was built with the money of a Dravidian philanthropist? Why have Brahmins behaved so mercilessly and fanatically as to push the communities of the Dravidian race even to starvation – death by adamantly enforcing their evil casteism,” asked Ramasamy.

On his return to Erode, Ramasamy took over his father’s business. When a deadly plague broke out in Erode in 1904, which claimed the lives of hundreds, he refused to leave unlike other local merchants and instead devoted his time to carry the dead for their last rites.

In the following decade, his business grew, besides acquiring many positions in public institutions.

All that changed in 1919, when he joined the Indian National Congress, where he extensively participated in the Non-Cooperation Movement. He was even arrested twice for his troubles. In April 1924, he earned greater acclaim for leading a successful agitation for the right of the lower castes to walk on roads near a Shiva temple in the holy town of Vaikom in present-day Kerala, despite strong opposition from the local priestly class and the Travancore royalty.

“In fact, the real public opinion in favour of the temple entry was created only by the Dravidian movement. The temple entry agitations were actually conducted by the followers of Thanthai Periyar from the 1920s. The Vaikom agitation under his leadership was not launched originally for the temple entry of untouchables. It was to give the oppressed the rights to approach and access the streets adjoining Sri Mahadevar temple at Vaikom,” writes K Veeramani, a social worker who worked closely with Ramsamy, in a blog for the Times of India.

In the following year, he left the Congress citing that it wasn’t doing enough to address the evils of caste discrimination within the party. In fact, this is something even BR Ambedkar had alluded to many times during his long-standing struggle for the emancipation of the Dalit community. Nonetheless, the Vaikom episode enhanced his position in the public eye.

In the following year, Ramasamy joined the historical Self Respect Movement started by another social reformer S Ramanathan. What Ramasamy did was propel the movement to new heights.

It espoused a vision of a society where so-called backward castes enjoyed equal rights while encouraging its members to attain self-respect despite the prevalence of a caste-hierarchy that did oppress them. Imbued with the spirit of rationalism and atheism, it wasn’t necessarily a movement against Brahmins, but the system of Brahminism. However, there are those who vehemently oppose this narrative.

What the movement sought was to end the scourge of pernicious superstitions, rituals, customs and traditions that perpetuated the dynamic of caste-based subjugation. “When others of his day loved to chant of political freedom, spiritual upliftment and other ‘bigger’ things of life, Periyar was down to earth enough to see that his people needed first and foremost their dignity to be salvaged and their self-respect to be restored. That was Periyar’s diagnosis of the society,” writes K Veermani.

“Self-respecters performed marriages without Brahmin priests (purohits) and without religious rites. They insisted on equality between men and women in all walks of life. They encouraged inter-caste and widow marriages [besides advocating property rights for women]. Periyar propagated the need for birth-control even from the late 1920s. He gathered support for lawful abolition of Devadasi (temple prostitute) system and the practice of child marriage. It was mainly due to his consistent and energetic propaganda, the policy of reservations in job opportunities in government administration was put into practice in the then Madras Province in 1928,” says this note in Counter Currents.

The Self Respect Movement had a tremendous influence on the future course of Tamil politics, deeply influencing the likes of CN Annadurai, MG Ramachandran, M Karunanidhi, and the two key political parties they started—the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) and All-India Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK). When the DMK government under CN Annadurai came to power in 1967 on back of the anti-Hindi agitation, it passed legislation legalising these ‘self-respect marriages’ much to the chagrin of many upper castes.

Read also: CN Annadurai: How a Schoolteacher Became Tamil Nadu’s First Political Stalwart

In the late 1930s, Periyar joined the Justice Party, which stood in opposition to the Congress in the Madras provincial elections. When the British conducted provincial elections in 1937, the Congress won, and C Rajagopalachari took charge. This began another critical chapter in the life of Ramasamy, who according to Ramachandra Guha in his book “Makers of Modern India”, “was increasingly known as Periyar”.

As soon as it took office, the Congress-led provincial government in the Madras Presidency, introduced compulsory Hindi instruction in schools.

This was a step, which would resonate with greater force in the violent anti-Hindi agitations of the 1960s. As the new president of the Justice Party in 1938, Periyar and members of the Self Respect Movement led protests to restore Tamil in schools. What brought greater political force to this demand was that these protests attracted even those opposed to Self-Respect Movement because of its emphasis on atheism. The provincial government soon had to withdraw this law.

During this time, Periyar’s politics began to shift significantly, and this is where we see his legacy on Tamil Nadu politics taking shape. “As Indian independence approached, Periyar grew apprehensive about the treatment of Dravidian people, a linguistic group including the Tamils, and he founded the Dravidar Kazhagam (Dravidian Organization) in 1944,” writes Ryan Shaffer, an American historian.

This split from the Janata Party also marked a definitive shift away from electoral politics for Periyar, while he further immersed himself in social reform. Unfortunately, his protégé CN Annadurai split ranks after a series of differences, especially over the question of participation in electoral politics.

Anna went onto establish the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) party. Despite breaking away from Periyar, Anna remained close to his ideals. Although the initial years saw the DMK following in the footsteps of Periyar, things began to change with the evolution of national politics and more pertinently, the Indo-China war of 1962, by which time Anna dropped his demand for secession from North India—an idea Periyar continued to advocate post-Independence. It’s hard to deny Periyar’s imprint on the historical anti-Hindi agitations of the 1960s.

Post-Independence he continued on his path of social reform—speaking out against the caste system, emphasising on the importance of Tamil while stressing the need to establish English as the national language instead of Hindi, and of course spreading the word of rationalism and atheism.

When arrested in 1953 on charges of blasphemy, he said, “an atheist is not rejecting the sayings or commandments of God, but the sayings and commandments that men made in the name of God.”

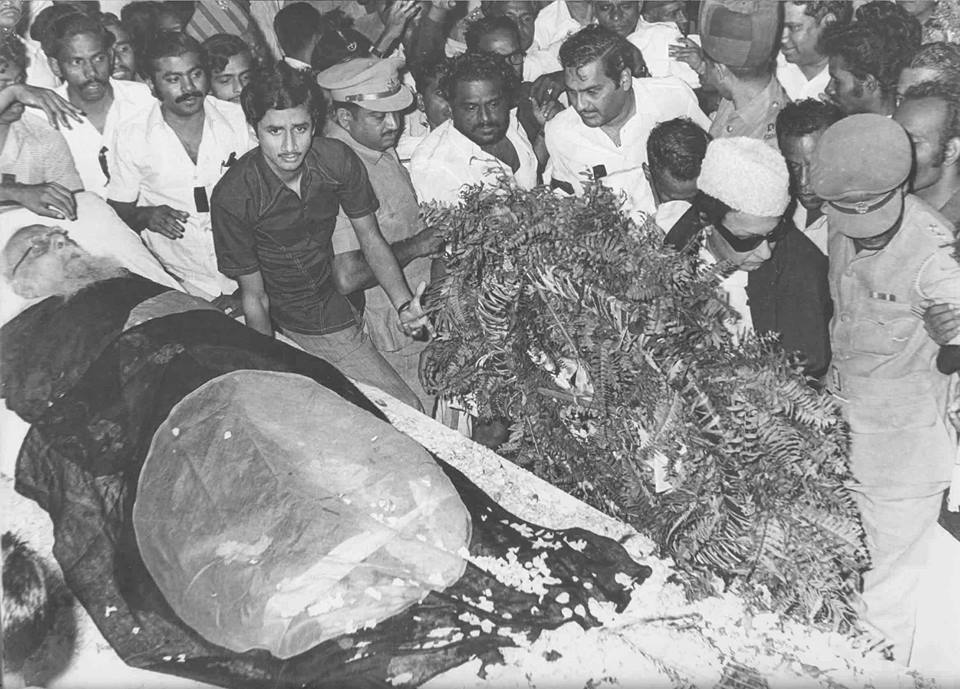

He passed away on December 24, 1973, and received a state funeral. Like any self-thinking maverick, Periyar’s legacy is complicated.

Supporters see Periyar as the apostle of social equality and rationalism. His critics, of which there are many, believe he did little to change attitudes against the caste system, and just partook in anti-Brahmin, anti-Hindu baiting.

However, one cannot deny the influence that Periyar had on not just Tamil politics for the next five decades, but also on progressive public discourse on women’s rights, rationalism, and the caste system. His writings on the subjects are both brilliant and relevant to this day.

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.