TBI Blogs: The Little Grain That Could – a Journey of Promoting Sustainable Agriculture in India

Lakshmee Sharma takes us on a journey of promoting sustainable agriculture in Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh through the William J. Clinton Fellowship for Service in India.

Lakshmee Sharma takes us on a journey of promoting sustainable agriculture in Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh through the William J. Clinton Fellowship for Service in India.

I completed a Bachelor of Arts (Triple Major) in Psychology, Sociology, and Literatures in 2014. No, that’s not a typo—I meant to say “Literatures“. One of the first things I learnt during this time was the importance of pluralism, especially of narratives. What I also learnt was that it is easy to politicize almost anything. The risk of sequestering oneself in the academic bubble is the tendency to problematise everything. This can be great in some occasions, but it’s a pain at parties. Trust me.

Of all the endeavours I’ve attempted thus far, the one I’ve gained from the most is choosing to study Sociology and Literature simultaneously. Oh yes, it offered me more than the ability of sounding passably erudite on a daily basis.

The curriculum was designed to offer bits and pieces of literatures from around the world. The biggest chunks, of course, were British, American, and Indian. I had a whole semester of American Literature, beginning from Whitman and ending with Ginsberg, with the Harlem Renaissance along the way. This semester was followed by Indian Literature, where we had Mahashweta Devi, Aijaz Ahmed, and a very informative piece by Amartya Sen about India and the so-called “West”.

What I’m trying to illuminate here is that the course went beyond looking at texts as mere texts. It implored the importance of context, history, politics, and culture when analyzing a text, because these factors determined whose narrative it was. This led me to Social Anthropology and its unique approach within the pantheon of social sciences. Anthropology gave me a new perspective to how development can be practised, and how single words can set the course of history (Person: Truman; Word: “Underdeveloped”).

It also taught me concepts of “positionality” and “ethnography”, which are equivalent to the proverbial “Alohamora” and “Accio” of Harry Potter fame, because I do believe they open doors and summon opportunities.

Anthropology and development should go hand in hand. A multiple narrative approach to understanding and eventually tackling development issues is gaining traction in both academia and practice today. “Heterodox” (I’m looking at you, economists) seems to be the buzzword, and I’m 100 % behind that!

At this point, you, the reader, might be wondering, “What’s this got to do with your millet obsession?” I’m glad you asked.

Understanding the context of an issue opens new channels of solutions. This is one of those instances where it is good to problematise. Applied anthropology is one way of going about this, and I thought I’d use this space to talk about the connotations of millet consumption in India through my own experiences, Fellowship and prior.

March 2016: Field Site, Karnataka

I’m on a scouting visit by myself to pick potential interviewees from a Kannada farming community to talk about State-led land acquisition and how it’s affecting them. I am invited in by a family of three, an elderly gentleman who has spent 40 years growing rice and millet, his wife who has done the same, and his brother.

After offering me some water, they ask if I’d like to have lunch.

The staple diet in most South Indian (particularly Karnataka and Tamil Nadu) agricultural households is finger millet (ragi) balls, and a spicy curry made of lentil and greens. I politely refused as I’d had a big breakfast.

The gentleman immediately tells his wife, “She doesn’t look like she eats ragi.” I interject, almost indignant, that my grandmother insists on eating ragi at least once a week, and I love it. The family immediately warms to me, and we spend almost two hours talking.

For those of you who’ve had the chance to read about the Indian Caste System, you might know how food is deeply entrenched in its maintenance and reproduction. Now, I don’t mean to generalise or reduce the practices of a heterogeneous South to one vignette, but finger millet is traditionally the diet of the farming classes and castes. The so-called “upper castes” (Brahmins) or land-owning castes usually consume rice and wheat as it is more expensive to grow (this is before the public distribution system’s implementation in India).

The availability of rice to all sections of society is more prevalent and normal today, but the caste and class associations of rice and ragi still underlie thought.

This was an interesting positional moment for me. I’m from a Tamil Brahmin family from urban Bangalore. However, the paternal side has some roots in agricultural life, as most families across castes had some farmland for subsistence. I spent most of my summers as a child in paddy fields with my grandfather. I grew up eating ragi like my family, and never once realised that what I ate could have so many connotations to it.

October 2016: Pokhrar, Uttarakhand

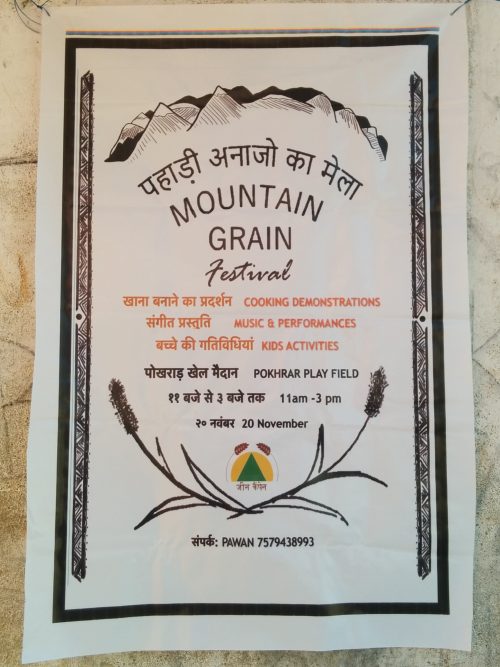

A few weeks before the Gene Campaign’s Pahadi Anajon Ka Mela, or The Mountain Grain Festival, my colleagues and I visited Pokhrar village to discuss options with local women farmers. The aim of the festival was to illuminate and reinforce the benefits of consuming millet in the hope that it would make an active comeback in their daily diet. We would do this through interactive and informative sessions on millet nutrition value, music, dance, and a real-time cooking demonstration session brought to them by yours truly (my Nigella Lawson moment, if you will).

During the initial discussions, I asked some of the women why the popularity of millet had taken a hit. There were a lot of interesting and practical reasons that surfaced—the Public Distribution System (PDS), cooking time, gas consumption, etc. The one that struck me, however, was when a lady said that children refuse to eat finger millet rotis because it is “black” in colour. They fear that consuming it would turn them dark, taking the “you are what you eat” adage quite literally. Now, what can I say to that?

My first internal reaction was anger. How can we have such prejudice about race, and towards our own people? Is the colonial hangover so strong that we’d imbue it to food, at the risk of losing out on precious nutrition? This is where an anthropological approach comes in handy. Understanding my own context, and the larger context of a nation in the process of forming its own post-colonial narrative, helped me greatly.

I couldn’t very well have a chat with them about race and caste relations in the world, and how it is wrong. That would be condescending and insensitive of me, especially when I could also be guilty of implicitly (sometimes explicitly) partaking of this way of thinking. Who am I to pontificate my own thoughts, acquired after years of conditioning and textbooks, in the reality of others? I think most fellows fresh out of academia would identify with this.

The theoreticians scoff at this reality, but the pragmatist finds a way around it.

The mela’s immediate plan of action was to pictorially, and through theatre, establish strong positive associations to finger millet. The power of the arts is long-standing and effective. Another way was to market our millet sweets as “barfis” or “chocolates” to appeal to the youngsters. I am very happy to say that the mela attendees polished off my 40 thick sweets in seconds.

Race and caste are just two contextual aspects of my experiences with millet. These are only some issues we are attempting to navigate. Now that we know the many contextual nuances of something like millet consumption, we have multiple approaches to tackle issues. This is just one of the facets of my work here.

Gene Campaign, my host organisation, promotes sustainable agriculture in Uttarakhand, Jharkhand, and Uttar Pradesh. I work in Orakhan village, Nainital district. The primary focus of my Fellowship is to promote millet consumption in Kumaoni villages. We create products using mountain grains which the women farmers of Kumaon would eventually manufacture and market.

Find out more about the Gene Campaign and how you can help here.

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167