TBI Blogs: How a ₹4,000 Crore Overhaul Is Underway in India’s Courts

India’s Law & Justice apparatus is a fundamental part of the country’s administrative system. Here’s how the Central Government hopes to allocate funding and resources to keep this essential component functioning smoothly.

India’s Law & Justice apparatus is a fundamental part of the country’s administrative system. Here’s how the Central Government hopes to allocate funding and resources to keep this essential component functioning smoothly.

In 2016, ‘vacancy in courts’ and ‘pendency of cases’ became buzz words, with occasional emotional outbursts from the custodians of our rights. In this analysis, let’s look at some of the polemic issues plaguing our justice delivery system, and whether budgetary allocations do justice (pun intended!) to those issues.

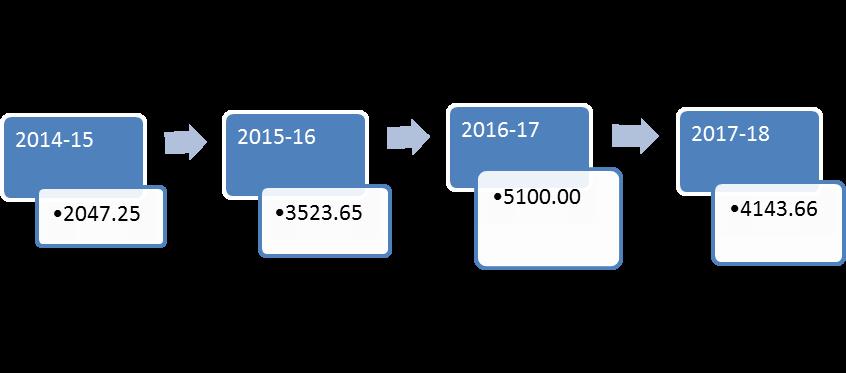

Total Budgetary Allocation for Law and Justice Ministry (in crores)

Overview

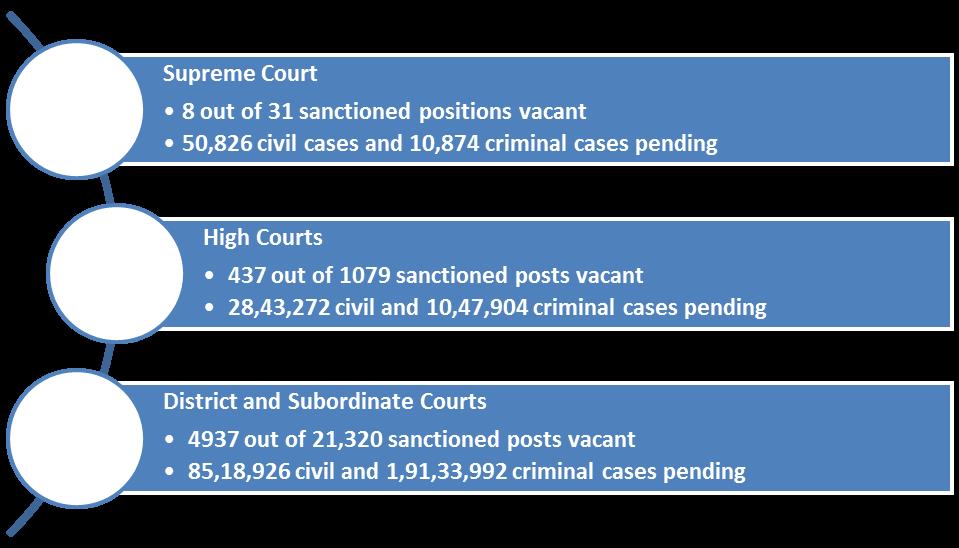

Access to Justice is a multi-faceted concept, and is in turn affected by a number of different variables—vacancy of judges in courts, pendency of cases, adequate investment in infrastructure, alternative dispute resolution means, etc. We look at some relevant statistics below (most recent):

Infrastructure as a barrier to Access to Justice

It cannot be said that if all these vacancies were filled, the pendency of cases will drastically come down. The reasons are that even with these sanctioned posts, the judge-population ratio will be significantly lesser for our country as against the ratio of 50 judges for every 10 lakh people found in some developed countries.

At present, India has an average judge-population ration of 17.8 judges, with most of the bigger states – Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Andhra Pradesh – recording a ratio even less than the average.

It was reported that Chief Justice T.S. Thakur had asked for creation of 70,000 more posts to reach the ideal ratio. In questions asked in Parliament, the government goes all out in dismissing these clams by citing a Law Commission Report (245th) in which it found the Judge-Population Ratio an unscientific mean to ascertain the number of additional courts required to clear backlogs, even as it anticipates an increase in the number of cases as more and more people become literate and aware of their rights.

That being said, till we gain more clarity on how many additional courts are required, it is a no-brainer that every year, for the next many years, new courts are required, especially as we keep adding to the burden of the courts by enacting new laws which create new offences and penalties.

Yet, we find that the amount allocated for a Centrally Sponsored Scheme under which the Central Government gives grants to States for creating Infrastructure Facilities in High Courts and District and Subordinate Courts came down drastically a few years ago, and is increasing only gradually.

| Year | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 |

| Budgetary Allocation for Infrastructure Facilities in Judiciary | 936 | 562.99 | 600.01 | 629.21 |

| Actual Release of Funds (might not be the same as amount utilized) | 933 | 562.99 | 518.74 (upto 15.12.2016) | — |

What must also be noted is the fact that over a period of five years (2015-2020), ₹4,144.11 crores is supposed to be earmarked for creation of 1,800 fast-track courts. With negligible increase in the budgetary allocation since 2015, this amount is not likely to be met from grants given to state governments by the Centre. States will be left to fend for themselves and that doesn’t give us much hope, as explained later.

But, it is curious to note that despite maintaining a near perfect allocation-release balance, the scheme was cut down. One explanation could be the 14th Finance Commission recommendations, which the government accepted and implemented in the 2015-16 budget. As per this report, states would receive a larger share of the untied funds from taxes, and as a result, the Central Government cut or reduced many Centrally Sponsored Schemes.

Now, even till 2016, many of the bigger states recorded a poor judge-population ratio, indicating that, on the face of it, states don’t seem to have spent the extra untied funds coming in on creating more courts and appointing more judges. This becomes problematic when we look at the next segment.

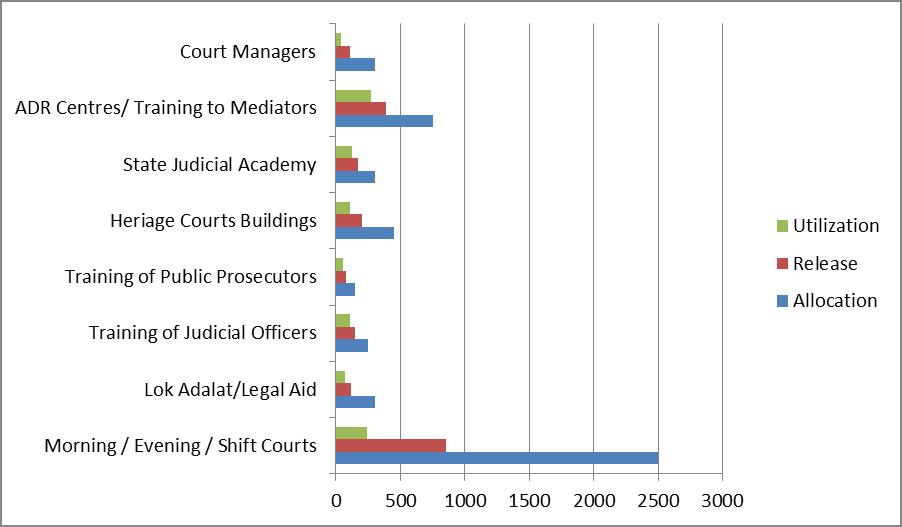

13th and 14th Finance Commission Reports

The 13th Finance Commission recommended a total allocation of ₹5,000 crore to the Justice Sector for the period 2010-2015. At the end of the five-year period, the government released only ₹2,067.93 crore, and out of that, utilised only ₹1,010.16 crore. The break-up for different items is provided below:

The extremely poor utilization rate is enough to show that law and justice isn’t exactly a priority for the government. Yet, in a document supplementing the Budget, the government notes with pride that at the end of 2015, “more court halls were available than the working strength of judges.” It seemed more like a justification for low utilization, as it’s not productive to keep creating infrastructure when there aren’t enough judges to use that infrastructure—almost a vicious circle.

Even then, considering the need for expansion required in this sector, the government made a comprehensive proposal to the 14th Finance Commission to increase the allocation of this sector to ₹9,749 crore, which the Commission accepted as well.

But what is shocking to note is that because the states received increased untied funds, the Central Government made no allocations to the states for the Justice Sector under the 14th Finance Commission, expecting them to incur these expenditures themselves.

As already pointed out, the motivation of states – even the more developed ones – to incur these expenditures doesn’t always translate into action.

Making Justice Accessible – Legal Aid and Gram Nyayalayas

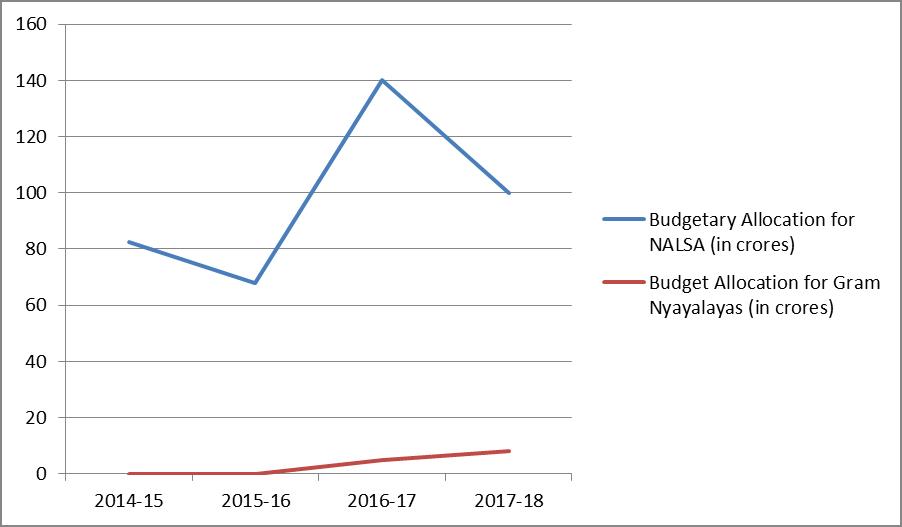

The National Legal Services Authority (NALSA) is a central authority which works to provide legal aid to eligible litigants, establish legal aid clinics, and organize lok adalats. Since it’s a central authority, it receives funding from the Central Government, and in turn allocates funds to Legal Service Authorities in states. As per the law, any member of Scheduled Caste, Scheduled Tribe community, a woman, a child, a mentally or physically disabled person, a victim of trafficking, an industrial workman, etc. is eligible for legal aid by the government (i.e. the state will pay legal counsels to represent them).

Gram Nyalayayas are essentially a manifestation of last-mile delivery of justice, where courts in villages settle disputes there itself, saving time, money, and the effort of travelling to cities. The Central Government provides grants to state governments for Gram Nyayalayas on the basis of intent shown by the state. Only 19 states have established Gram Nyayalayas, and out of 291 notified ones, only 175 gram nyayalayas are functional.

UP has the worst record, as just 2 out of 104 notified nyayalayas are functional.

Some relevant statistics related to these two initiatives are below:

53.4057.0455.57 (upto July 2016) – with 18 states and UTs not receiving any allocation

| 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | |

| Amount Allocated by NALSA to states (in crores) | |||

| Number of beneficiaries | 21,07,192 | 3,11,670 | 83,185 (upto March 2016) |

| Amount Released for setting up gram nyayalayas (in crores) | 3.00 | 2.11 | 5.00 |

There is scope for more funds for gram nyayalayas, but the initiative needs to come from the states. 72 % of the amount released for gram nyayalayas since 2009 is of a non-recurring nature. It seems that after their establishment, the onus is on the state governments to run and maintain the same. There isn’t much incentive for the state governments to take up this exercise. If the Centre made higher allocations and covered up more recurring expenditures, more states would open gram nyayalayas.

Curiously, between 2014 and 2016, the allocation for legal aid went up, but the number of beneficiaries came down drastically. The cut in allocation for NALSA in this year’s budget is also not understandable.

NALSA also helps establish and maintain Legal Aid Clinics in law colleges. But as of January 2016, only 1,575 such clinics were operating in the country. Further, a total of 2,901 legal aid institutions operate at various levels – state, district, and taluka levels – across the country. Again, there is a much larger scope for increasing budgetary allocation for NALSA. Any budget cut is unjustified, even on the back of the “higher devolution under 14th Finance Commission” argument.

Judicial Reform and E-courts

Judicial reform again is a multifarious exercise. Let’s look at some budget-related components which are likely to make justice swift and less burdensome in India.

The government has been making allocations for the National Mission for Justice Delivery and Legal Reforms. The Mission undertakes structural changes and capacity enhancements to reduce arrears and delay in the system. E-Courts is one major step in this direction. We look at budgetary allocation for E-courts:

| Budgetary Allocation (In crores) | 2014-15 | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 |

| e-Courts | 58.00 | 2.00 | 256.00 | 416.00 |

The Ministry undertook computerization of Courts on a mission mode in 2007. At a cost of ₹441 crore, it decided to computerize about 13,000 district and subordinate courts over two years. The period kept extending, and so did the cost. Eventually, at a budget of ₹935 crore, the government said it would computerize about 14,000 courts by 31st March 2015. As per the government’s own estimate, it more or less achieved this with a completion rate of 94 %. In July 2015, the government launched Phase II at a budgetary outlay of ₹1,670 crore spread over four years.

It seems that between 2015 and 2016, the government didn’t achieve much under the Phase II Mission. Even the completion rate for Phase I remained constant between March 2015 and March 2016. Even for the 2017 allocation, the Ministry wants to computerize 1,000 courts which the Mission couldn’t cover in Phase I. The government must not repeat the mistakes it made in Phase I, and incur time and cost overrun again.

Conclusion

The overall drop in budgetary allocation doesn’t bode well for the justice administration, struggling with its vacancies and pendencies.

If you have any inputs on the above analysis that you’d like to get to MPs, fill an online form here.

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.