Barking Up The Right Tree: The Fascinating History of Tree Conservation Movements in India

Enshrined in folklore, documented in historical texts and reflected in the daily lives of people is a multitude of evidence that supports the fact that coexistence with nature has been an integral part of Indian culture since time immemorial.

As Rabindranath Tagore once wrote in his essay Tapovan, Indian civilisation grew from the forest and learnt its principles of democracy and diversity from it. Enshrined in folklore, documented in historical texts and reflected in the daily lives of people is a multitude of evidence that supports the fact that coexistence with nature has been an integral part of Indian culture since time immemorial.

In ancient India, environment was not an isolated entity, independent of mankind.

Photo Source

The relationship between people and the environment in ancient India was one of harmony, coexistence, mutual care and concern – the two supporting and complementing each other in their own way. For instance, some of the fundamental principles of ecology – the interrelationship and interdependence of all life – are reflected in the ancient scriptural text, the Isopanishad. It says:

“Each individual life-form must learn to enjoy its benefits by forming a part of the system in close relation with other species. Let not anyone species encroach upon the other’s rights.”

The concept of participatory forest management was also prevalent in ancient India as illustrated by the examples of village committees overseeing the maintenance of panchavatis (a cluster of five types of trees) in the ancient Indian forest texts or Aranyakas. Vedic-era traditions also affirm that every village will be complete only when certain categories of forests are protected i.e mahavan (the natural forest), shrivan (the forest of prosperity) and tapovan (the forest of religion).

The post-vedic period saw the evolution of various ethno-forestry practices and cultural landscapes for conservation as agriculture emerged as the dominant economic activity. The most prominent ruler in ancient India who focused on clean environment and wildlife conservation was Emperor Ashoka.

Photo Source

Under him, the Mauryan state maintained the empire’s forests, along with fruit groves, botanical pharmacies and herbal gardens that had been established for the cultivation of medicinal herbs. Hunting certain species of wild animals was banned, forest and wildlife reserves were established and cruelty to domestic and wild animals was prohibited.

In one of his minor edicts, Ashoka states:

“Wherever medical herbs suitable for humans or animals are not available, I have had them imported and grown. I have planted mango groves, and I have had ponds dug up and shelters erected along the roads at every eight kilometers. I have had banyan trees planted on the roads to give shade to man and beast.”

One of the finest examples of tree conservation practices that arose in ancient India has been the maintenance of certain patches of land or forests as “sacred groves” dedicated to a village deity. Protected and worshiped, these sacred groves are found all over India, especially along the Western Ghats.

In Kerala, there are hundreds of small jungles called sarpakavus dedicated to snakes.

Photo Source

In Kodagu district in Karnataka, the Kodava tribe has maintained over a thousand Devakadu groves dedicated to Aiyappa, the forest god. Along river Tamraparani in Tamil Nadu, there are 150-odd temples, each with a sacred grove called nandavanam that provides a window into an ecosystem’s past. Devrais in Maharashtra, kovilkadus in Tamil Nadu and pavitraskhetralu in Andhra Pradesh are other examples of sacred groves in south India.

The Gujjars of Rajasthan have a unique practice of planting neem trees and worshiping the groves as the abode of their deity, Devnarayan. Interestingly, Mangar Bani, the last surviving natural forest of Delhi, is also protected by Gujjars of the nearby area.

Photo Source

Among the largest sacred groves in north India are the ones in Hariyali, near Ganchar in Chamoli district of Uttarakhand, and the Deodar grove in Shipin near Shimla in Himachal Pradesh. There are several other sacred groves as well called deobhumis in Himachal, beeds in Haryana, sarnas in Jharkhand, jaheras in Odisha and harithans in West Bengal.

Northeast India too has a well-documented culture of sacred groves. The most famous of these are the law kyntangs of Meghalaya – two large groves being in Mawphlang and Mausmai – that are associated with every village to appease the forest spirit. The thans of Assam, mauhaks of Manipur and gumpa forests of Sikkim and Arunachal Pradesh too act as reservoirs of rare fauna, and more often rare flora, amid rural and even urban settings.

Photo Source

Handed down through the ages, this love and respect for nature pervaded community life across India and saw expressions from across the land. The legendary Tamil philosopher, Thiruvalluvar, talks of nature as man’s fortress. If he destroys her, he remains without protection.

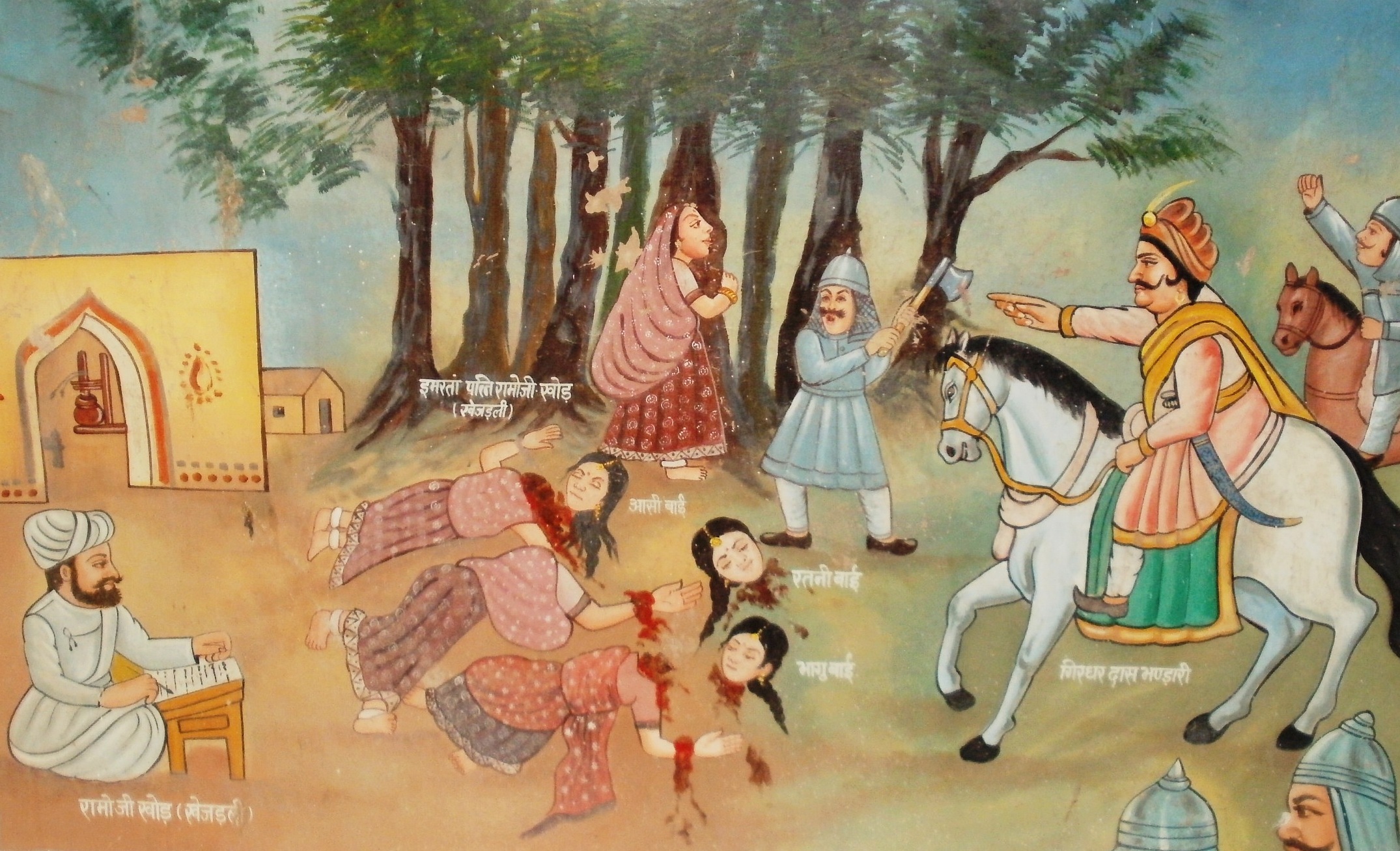

However, nowhere is this deep ecological consciousness better exemplified than in the supreme sacrifice of the Bishnois in Khejarli a village in Jodhpur district of Rajasthan. The name of the town is derived from Khejri (Prosopis cineraria) trees, which were in abundance in the village.

Photo Source

In 1730 AD, the then-ruler of Jodhpur, Maharaja Abhay Singh, had ordered the felling of the village’s khejri trees in order to bake lime for the construction of his new fort. A royal party led by Giridhar Bhandari, a minister of Jodhpur, arrived at the village with the intention of cutting trees for the said purpose. A local woman called Amrita Devi was the first one to refuse to acceded to this demand. She famously said,

“Sar sāntey rūkh rahe to bhī sasto jān (If a tree is saved even at the cost of one’s head, it is worth it).”

Having said this, Amrita Devi and her three young daughters hugged the trees to protect them from being felled and were axed along with the trees. The news spread like wildfire, sparking off a strong collective protest from the local Bishnoi community. Nearly 363 Bishnoi men and women, young and old, placed their heads against the trees to prevent them being cut and were axed along with the trees.

When the Maharaja heard about their sacrifice, he was so moved that he immediately apologized for the mistake committed by his officials and issued a royal decree that prohibited the cutting of green trees and hunting of animals in and around Bishnoi villages.

You May Like: How One Determined Woman Single-handedly Electrified Her Village and Took on the Timber Mafia

At a time when the world had scarcely become aware of ecological consequences of deforestation, the Bishnois laid down their lives to protect their beloved trees in probably the first and most fierce environment protection movement in the history of the country. In 1970s, this sacrifice became the inspiration behind the famous Chipko Movement.

Chipko – “to stick” in Hindi – was a people’s movement against mindless deforestation. Poor village women in the hills of northern India determinedly hugged trees to prevent them from being cut down by the very axes of forest contractors that also threatened their lives.

Photo Source

Chipko’s first battle took place in early 1973 in Chamoli district, when the villagers of Mandal, led by Chandi Prasad Bhatt, Sunder Lal Bahuguna and the Dasholi Gram Swarajya Mandal (DGSM), prevented an Allahabad-based sports goods company from felling 14 ash trees. The movement quickly spread across the villages in the region, with simple yet effective action eventually saving 12,000 sq.km. of a sensitive water catchment area from deforestation.

The Chipko protests in Uttar Pradesh achieved a major victory in 1980 with a 15-year ban on green tree felling in the Himalayan forests of that state. The success of Chipko movement gave rise to many similar resistance groups in India, including Appiko in Karnataka, as well as laws that restored some control over forests to the people living in and around them. Started by Pandurang Hegde in September 1983 at Salkani, the Appiko movement had a ripple effect not only in Karnataka but also in parts of Kerala and Tamil Nadu.

The next major milestone in the history of tree conservation movements in India was the Save Silent Valley protest, a remarkable people’s movement that saved a pristine evergreen forest in Kerala’s Palakkad District from being destroyed by a hydroelectric project.

Photo Source

When nature-loving citizens and conservationists learned that the proposed hydroelectric dam would submerge a part of the forest, they campaigned for more than a decade to prevent it from happening. Although the campaign did not have any centralized planning, it was highly effective.

Also Read: One Man Helped Create One of India’s Most Famous National Parks 32 Years Ago. This Is His Story.

The sustained pressure exerted on the government by citizens using every possible means available at the time – letters to the editors of newspapers, seminars, widespread awareness programmes, petitions in court and finally direct appeals to the Prime Minister – proved ultimately successful. In 1986, Silent Valley was declared a National Park, a striking testimony to the power of peoples’ action.

Another iconic tree conservation movement was Jungle Bachao Andolan, which took shape in the early 1980s. When the government proposed to replace the natural sal forest of Singhbhum district in Bihar with commercial teak plantations, the local tribals rose up in protest. The movement, which spread to nearby states, highlighted the gap between the aims of the Forest Department and the local communities.

The story of tree conservation in India would be incomplete without the mention of two truly inspiring green crusaders – Saalumarada Thimmakka and Jadav “Molai” Payeng.

Photo Source Left/Right

Now 105, Thimmakka earned the prefix Saalumarada, meaning a ‘row of trees’ in Kannada, for planting and tending to 400-odd banyan trees along a 4 km stretch between Hulikar and Kudur. The centenarian has said she and her husband began planting and taking care of the banyan saplings after relatives and neighbours ostracized her for being unable to bear a child.

Assam’s Jadav Payeng has single-handedly grown a sprawling forest on a 550-hectare sandbar in the middle of the Brahmaputra. It now has many endangered animals, including at least five tigers, one of which bore two cubs recently. It was in the summer of 1978 when Payeng, then a teenager of the Mishing tribe, decided to grow a forest on a barren sandbar to help the animals of the area. Read more about him here.

Today, conservation movements throughout the country have moved beyond just protecting trees: they integrate waste management, preservation of wildlife, cleaning of water bodies and more. Nonetheless, there is an urgent need to refocus on conserving the fast-eroding green cover in urban landscapes.

And that’s precisely why in Bengaluru, a group of concerned citizens have come together to honour trees through a unique festival called Neralu.

The third edition of this citizen-driven urban tree festival will be held on February 18 and 19 at the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) and other venues across the city. Naturalists, ecologists, artists, authors, photographers and homemakers have been meeting every Sunday at Cubbon Park to plan the two-day event which is crowd-funded; there’s no entry fee. Know more here.

Like this story? Have something to share? Email: contact@thebetterindia.

NEW! Log into www.gettbi.com to get positive news on WhatsApp.

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167