Power off, Nature On! How India Is Reconnecting With Her Wild, Organic, Responsible Side.

In which we unearth stories of homegrown vegetables, organic cafes and eco-warriors finding new ways to incorporate the natural into everyday living.

In which we unearth stories of homegrown vegetables, organic cafes and eco-warriors finding new ways to incorporate the natural into everyday living.

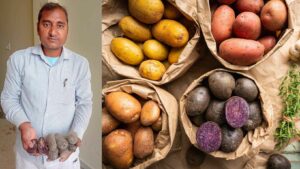

Green is starting to peek through crevices in the concrete jungles of India’s cities. In her villages, where just a few years ago tired soil was being ploughed for yet another annual crop, locals are finding new ways to till the earth using only the natural.

More and more adults admit to feeling the collective guilt of not being able to provide the next generation with things that they took for granted in their own childhoods; a game of football on the local maidaan, vacations spent riding bullocks or chasing through coffee plantations, or the simple luxury of tossing a handful of fresh kadipatha into simmering oil straight from the herb garden outside the kitchen.

Burgeoning economic development has connected remote villages with metropolises and provided many with the sort of financial security their parents never knew.

But progress has come at a price, and those that recognise the opportunity cost are making an active effort to find alternatives.

Slowly, urban India is seeing a resurgence in plant life. Olive green creepers now spread across the awnings of airy, city restaurants and balcony gardens lend life to previously cramped flats.

In the south, the Garden City of Bengaluru is striving to live up to it’s moniker. In the shadow of a monstrous skyscraper being erected on Sampige Road, across a traffic-clogged street, an organic terrace garden filled with tulsi, chilli, lime and rosemary pumps oxygen into air tainted by the coughing of blackened exhaust pipes. This is The Green Path Organic State, an eco-initiative that houses an eco-store and organic cafe.

The quiet, green space, cocooned amidst the worst of city life, is testament to changing priorities and a newfound balance that civilisation is seeking with nature. Here, one can buy herbs for Rs. 50 a pot, have a wholesome lunch of raagi rotis and beetroot fresh from the farm and stock up on organic alternatives at the in-house store.

I speak to Sriram Aravamudan of My Sunny Balcony, a company that sets up gardens in urban spaces, who reaffirms the shift.

Photo Credit: My Sunny Balcony

“Considering that the average vegetable travels 400 km from farm to table, even growing a single tomato plant at home can reduce the global carbon footprint significantly,” he says. “Modern gardening trends steer clear of ornamentals and exotic plants, and opt for trendy, designer vegetable gardens instead. At MSB, we always make it a point to include vegetables and herbs in all our garden projects. Our clients too are very keen on growing as much produce as they can at home. Aside from having direct control over what they put into the food they eat, they also get the satisfaction of reaping the fruits of their labour.”

One of their recent projects involved setting up a Square Foot planter bed at the Munchkins Montessori & Day Care so that gardening could be incorporated into their early learning curriculum.

Today, toddlers at the school grow their own mint, lemongrass and coriander plants in boxes made with recycled wood, and filled with an easy-to-dig organic mixture of garden soil, cocopeat and vermicompost.

Photo Credit: My Sunny Balcony

This isn’t a standalone case.

Kapil Mandawewala of Edible Routes, a Delhi-based eco-initiative that has set up similar vegetable patches at the Happy Model School in Janakpuri, Commercial Secondary School in Daryaganj and The Lotus Petal Foundation in Gurgaon, says, “As people living in cities we’ve lost a connection with our food. We don’t know where it comes from and who’s growing it. Most people don’t know how to go about growing their own food: what to grow where, or how much to produce. Once those initial hurdles are crossed, and as a person grows their first basket of spinach or first pot of tomatoes, they really start connecting with it.”

On the research front as well, going back to the basics is being recognised as vital to sustainable development.

For example, Dr Anil Kumar Sharma, Professor at Uttarakhand’s G. B. Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, studies how microbes can be used to improve existing organic farming techniques.

“There is a major focus on organic farming here [Uttarakhand]. The government also promotes it by giving farmers incentives to go organic and creating markets for organic produce within the state,” he says proudly.

***

It’s Only Natural

“My cousin was seven, and he thought that tomatoes came from supermarkets.”’

When Janani Eswar found herself confronted with a generation of children who didn’t know rhizome from tuber, she decided to do something about it. She herself had been homeschooled as a child, so the garden was as much her classroom as anywhere else. When she discovered that her experiences — of being reared amidst nature — were more privilege than practice, she began GRIN (Growing in Nature), an initiative that spearheads programmes to provide children with a good dose of the Great Outdoors.

“Children today actually need to be told that it’s okay to get dirty!” she exclaims. “I’ve made it my mission in life to connect children to nature.”

Now she spends the weekends tramping through Bangalore’s Cubbon Park with a troupe of wilderness explorers and works with government school kids to set up and care for their own organic gardens on campus. Janani speaks of connecting with nature as a tactile, sensory experience, pointing out tangible side-effects to deprivation.

Dr. Vandana, who runs the Urban Mali Network, recognises communities of agriculturists whose skills are often wasted because they move to cities in search of lucrative careers. Through the network, she employs them to set up urban farms for clients across her city, using the principles of natural farming. She makes a deliberate effort to use only native plants that attract more urban biodiversity. She, too, observes a growing trend in organic vegetable farming within homes and apartment complexes, citing the example of a project that involved setting up an aesthetic, but functional, vegetable garden for a family that now only consumes what they grow.

Both GRIN and the Urban Mali Network operate under ArtyPlantz, a platform whose stated mission is to “incubate social entrepreneurs who heal lands and minds.”

Organic farming has taken root, so to speak, in the most unlikely of places.

Kapil’s initiative, Edible Routes, also runs a full-fledged farm on a leased 2-acre plot that grows over 50 varieties of greens and vegetables. The organisation conducts workshops to handhold amateur gardeners, sells plant boxes and landscaping material, and sets up and maintains terrace gardens and organic farms in homes, schools and corporate spaces in and around the NCR region, as far as Meerut and Ludhiana.

He says, “There is so much that can be done with home gardens or even public parks and spaces being used as dump yards. We want to encourage that.”

***

To Dust Returnest

The Marudam Farm School sprawls across eight acres of an organic farm in Tiruvannamalai, Tamil Nadu. Education here is as much about training the body as the mind.

Students and teachers start their day early, tending to the campus farm and vegetable gardens.

Once a week, the troupe looks forward to a walk on the nearby Arunachala hill, where the land is viewed as an educational resource. Often, these trips involve learning important lessons about local flora and fauna, making an effort to retain a physical connection with nature. The school operates under the aegis of The Forest Way, a registered non-profit charitable trust, so students also have the benefit of engaging with the organisation’s programmes such as lending a hand during planting season, filling packets with soil for the nursery, conducting surveys and working on landscaping.

I speak to V. Arun, founder of the school, on his approach to alternative education. “It’s not being done enough,” he says straight away. “Aside from lip service programmes where organisations conduct one or two workshops in schools, schools are not really incorporating the environment into their teaching. A few workshops won’t help. It needs to be a way of life.”

He tells me how his students assist labourers working on their farm, where — depending on the rain — upto 85% of the rice, lentils and vegetables consumed on campus are grown.

A few years ago a new student arrived at Marudam, after having dropped out from school at his hometown in Andhra Pradesh. Despite being the son of a farmer, he had never taken an interest in agriculture. His stint at Marudam was supposed to be two months; he ended up staying two years, dabbled in organic farming and returned to his village where he took over his father’s land and trained him in organic farming methods such as heavy mulching, not typically practiced by rural farmers. He also set up a tree nursery and encouraged his younger brother to enrol at Marudam.

Similarly, several other schools have begun to recognise the importance of imparting life skills to students. Institutions the Prakriya Green Wisdom School and the Bhoomi College are eco-friendly, renewable energy-operated spaces that ensure their students and faculty tune into nature on a daily basis, contribute to the garden and kitchens.

The Tamarind Tree school in Dahanu brings nature into the classroom and takes the class outdoors, acting as a watchdog for the local environment. The Good Shepherd International School in Ootacamund has been called India’s Greenest School for it’s efforts in soil management, organic farming and organic waste management.

While the impact individual organisations such as these have is noteworthy, their scattered nature makes it difficult for them to reach more than a few students.

That’s where initiatives like Pune-based Lend a Hand India come in.

The NGO began informally in 2006 with $500 and is a $1,00,000 company today, funded by the likes of JP Morgan and the MacArthur Foundation. Founders Raj Gilda and his wife Sunanda Mane believe the reason the organisation has such widespread impact is because it chose to work with existing channels rather than subvert them. Today their staff members have representation in State Education Departments and indirectly help shape policy.

“We realised that we would only impact large numbers if we could get our programme established within the system,” Raj explains. “It has now been approved by secondary school State Boards in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Andhra Pradesh and is soon to be recognised elsewhere too. Our programmes were first introduced under SUPW classes, but in 2014 they were recognised as full-fledged 100-mark subjects.”

Lend a Hand believes in providing students with a whole gambit of life skills — not necessarily vocational — right from engineering skills like welding, electrical wiring and carpentry to skills required for basic healthcare, agriculture, gardening, landscaping and the usage of renewable energy. As part of their programmes, they recruit local farmers, welders and electricians and train them to instruct at local schools weekly.

Raj describes how farming programmes are among the most popular, especially in urban areas where students otherwise have little opportunity to get their hands dirty.

“The biggest challenge in the country today is that no one wants to do farming. The next generation of farmers’ kids are college graduates, who want to leave the business. But they’re not necessarily getting jobs. We’re trying to promote a love for working with your hands and the soil. Through our programmes students learn things like soil testing and drip irrigation. They’re not experts at the end of it but it does give them practical orientation.”

Initiatives like Gilda’s could go a long way in changing the way the next generation incorporates nature into their quotidian lives. While programmes such as his are a contrived effort for many today, for the current generation of millennials, there is real glamour in the dirt.

***

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter.

NEW: Click here to get positive news on WhatsApp!

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.