Anna Mani Is One of India’s Greatest Woman Scientists. Yet You Probably Haven’t Heard Her Story

A distinguished meteorologist, Anna Mani was the former Deputy Director General of the Indian Meteorological Department and made significant contributions in the field of solar radiation, ozone and wind energy instrumentation. Here's her inspiring story.

One of the most talked about images from India’s Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) was that of ISRO’s women scientists celebrating the success of the mission. While it may have been the very first time many Indians were seeing a visual of women working in the sciences, they definitely weren’t the first ones. Many other brilliant, dedicated and determined Indian women have pursued science over the years.

Here’s the little-known story of one of India’s pioneering women scientists, Anna Mani. A distinguished meteorologist, Mani was the former Deputy Director General of the Indian Meteorological Department and made significant contributions in the field of solar radiation, ozone and wind energy instrumentation.

Photo Source

Anna Modayil Mani grew up in a prosperous family in Travancore, a former princely state in the southern part of India, now part of the state of Kerala. Born in 1918, she was the seventh of eight siblings. Anna Mani’s father was a prosperous civil engineer who owned large cardamom estates in the region.

The Mani family was a typical upper-middle class professional household, where sons were groomed for high level careers from childhood while daughters were primed for marriage. Back then, there was a consensus in society that education for women should be tailored to their particular roles as mothers and homemakers. But little Anna Mani would have none of it. Her formative years were spent engrossed in books.

By the time she was eight, Mani had read almost all the Malayalam books available at her local public library. On her eighth birthday, when she was gifted with diamond earrings- as was the custom in her family- she opted instead for a set of Encyclopaedia Britannica.

By 1925, Travancore had become the epicentre of the Vaikom Satyagraha. People of all castes and religions across the princely state were protesting the decision by the priests of a temple in the town of Vaikom to bar dalits from using the road adjacent to the temple.

![019PHO000430S45U00046000[SVC2]](https://en-media.thebetterindia.com/uploads/2017/01/019PHO000430S45U00046000SVC2.jpg)

Photo Source

It was during this time that Mahatma Gandhi came to Viakom to lend his support to the civil disobedience movement. The satyagraha movement, the swadeshi philosophy and especially, Gandhi’s visit in its support, made a deep impression on the young and idealistic Anna. Drawn to Gandhian principles, the little girl took to wearing only khadi as a symbol of her nationalist sympathies.

Her strong sense of nationalism also instilled in her a fierce desire for personal freedom. Instead of following the footsteps of her sisters (who got married in their late teens), she insisted on pursuing higher studies. While her family did not oppose her wish, they offered little encouragement.

Mani wanted to study medicine but when that was not possible, she decided in favor of physics because she happened to be good in the subject. So, she enrolled in the honours programme in physics at Presidency College in Madras (now Chennai).

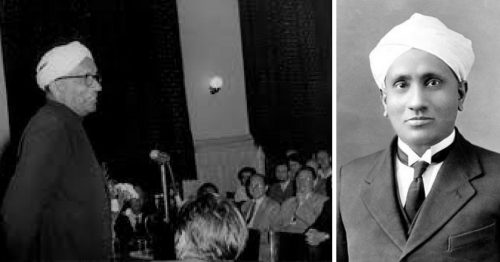

In 1940, a year after finishing college, Anna Mani obtained a scholarship to undertake research at the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. She was accepted in no less than Nobel laureate C V Raman’s laboratory as a graduate student and worked on the spectroscopy of diamonds and rubies.

Photo Source

During this period, Raman’s laboratory housed a collection of 300 diamonds from India and Africa; practically all his students worked on one aspect or the other of diamonds. Mani recorded and analysed fluorescence, studied absorption and temperature dependence, and the Raman spectra of 32 diamonds.

The experiments were long and painstaking, sometimes requiring 15 to 20 hours. Mani spent long hours at the laboratory, often working through the night. Between 1942 and 1945, she published five single-authored papers on luminescence of diamonds and ruby. In August 1945 she submitted her PhD dissertation to Madras University and was awarded a government scholarship for an internship in England.

Also Read: 7 Incredibly Smart Indian Women Scientists Who Make Us All Proud

The scientific institutions, however, perpetuated their own gender biases. Madras University, which at that time formally granted degrees for work completed at the Indian Institute of Science, claimed that Mani did not have a M.Sc. degree and therefore could not be granted a PhD. They chose to overlook that Anna Mani had graduated with honours in physics and chemistry, and had won a scholarship for graduate studies at the Indian Institute of Science on the basis of her undergraduate degree.

Photo Source

Despite her pioneering work, she was never granted a doctoral degree and today her completed PhD dissertation remains in the library of Raman Research Institute, indistinguishable from others. Fortunately, the lack of a PhD never deterred her. Utilising the government scholarship for an internship in England, Mani went on a troop ship to the Imperial College in London to pursue physics in 1945. However, she ended up specializing in meteorological instrumentation as it was the only internship available.

When Mani returned to independent India in 1948, she joined the Indian Meteorological Department at Pune. Put in charge of construction of radiation instrumentation, she had to make do with what was available. Never compromising quantity for quality, she inspired the scientists under her to put in their best. “Find a better way to do it!” was her motto.

Anna Mani standardised the drawings for nearly 100 different weather instruments and started their production. During the International Geophysical Year (1957-58), she set up a network of stations in India to measure solar radiation. She also published a number of papers on subjects ranging from atmospheric ozone to the need for international instrument comparisons and national standardisation.

Photo Source

Furthermore, she undertook the development of an apparatus to measure ozone – ozonesonde. This enabled India to collect reliable data on the ozone layer. Thanks to Mani’s singular contribution, she was made a member of the International Ozone Commission. In 1963, at the request of Vikram Sarabhai (Father of India’s Space programme), she successfully set up a meteorological observatory and an instrumentation tower at the Thumba rocket launching facility.

In 1976, Anna Mani retired as deputy director general of the Indian Meteorological Department and subsequently returned to the Raman Research Institute as a visiting professor for three years. Later she set up a millimetre-wave telescope at Nandi Hills, Bangalore. She published two books, The Handbook for Solar Radiation Data for India (1980) and Solar Radiation over India (1981), which have become standard reference guides for solar tech engineers.

A visionary, Anna Mani knew/foresaw that alternative sources of energy would have a big role to play in India’s future development. She organised round-the-year wind speed measurement from over 700 sites using state-of-art equipment.

Later, in Bangalore, Anna Mani started a small workshop that manufactured instruments for measuring wind speed and solar energy. She hoped that the instruments produced in her workshop would help in development of wind and solar energy in India. Today, as India takes a lead in setting up solar and wind farms across the country, part of the credit goes to Mani.

Photo Source

Asked whether being a woman had any impact on her work, the stoic and proud Anna Mani would insist that she “had worked hard to gain my academic qualifications and was judged fit to carry out the work that was needed.” However, she would recall how even a slight error made by her or other women scientist in handling instrumentation or in setting up an experiment would be immediately broadcast by some men as a sign of female incompetence.

This aside, she gratefully remember the warmth with which a few of her male colleagues, especially their wives, welcomed her into their homes. Mrs Raman, who she had grown close to during her days at IISc, treated her like her own daughter.

Devoted to her studies and research, Mani never married. Passionate about nature, trekking and bird watching, she was a member of many scientific organizations – Indian National Science Academy, American Meteorological Society, and the International Solar Energy Society etc. In 1987, she received the INSA K. R. Ramanathan Medal for her achievements. In 1994, she suffered from a stroke that left her immobilised for the rest of her life. She passed away on August 16, 2001, in Thiruvananthapuram.

In 1913, the year of Amma Mani’s birth, the literacy rate for women in India stood at less than 1 percent. Even in 1930, when Mani went to college, opportunities for women to pursue further studies or a career in science were very limited. A woman who spent her life in the pursuit of science, the pragmatic Mani saw nothing unusual in her pursuing physics in an era where it was possible to count all the women physicists in India on one’s fingertips. It’s time India remembers this amazing woman and her exemplary contribution to the world of meteorology.

Here is an NGO that is working to close the gender gap in STEM fields in India.

A not‐for‐profit organization based in Delhi, Feminist Approach to Technology (FAT) believes in empowering women by enabling them to access, use and create technology through a rights‐based framework. The NGO has started a pilot project called the Jugaad (Innovation) Lab to explore how hands-on STEM learning in a feminist environment can encourage and support girls to pursue STEM education.

The Lab has been created as a space for girls to learn about STEM through doing – a place where they can tinker, build, break and rebuild stuff to learn through hands-on work and experimentation – while also understanding the patriarchal structures and systematic discrimination that prevents them from accessing opportunities in STEM and how they can counter such challenges. As of now, 25 girls between the age of 10 to 15 are enrolled in the Lab.

You May Like: Meet India’s First Woman PhD in Botany – She Is The Reason Your Sugar Tastes Sweeter!

Like this story? Have something to share? Email: contact@thebetterindia.

NEW! Log into www.gettbi.com to get positive news on Whatsapp.

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.