How Suchitra Sen Used Indian Cinema to Revolutionise the Public Image of a Woman in the 1960s

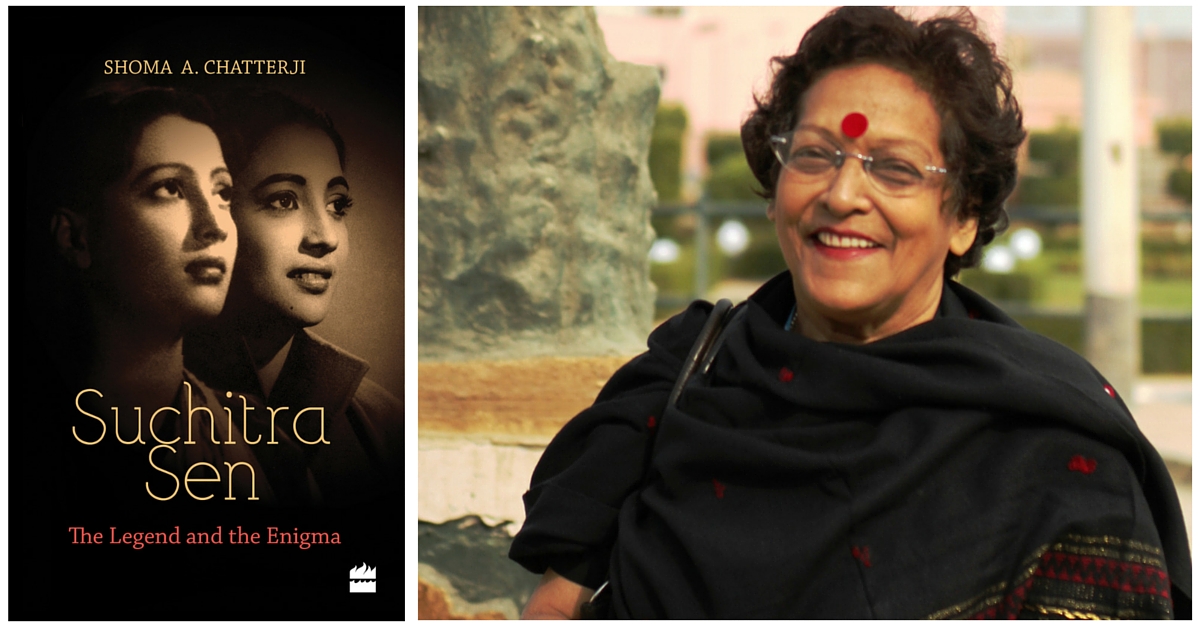

This excerpt from Suchitra Sen: The Legend and the Enigma by Shoma A Chatterji looks at Sen as the quintessential working woman, who effortlessly portrayed the dedicated professional woman in many of her films, someone who attempted to create a balance between the demands of love and romance and work.

Suchitra Sen’s persona has many dimensions – as the legendary romantic star, who created mushy magic on 700mm; a powerhouse performer, who portrayed a working-woman on screen, at a time when women artists were seen as mere appendages to the narrative; and a woman who suddenly called it quits and willfully withdrew from public gaze completely. This excerpt from Suchitra Sen: The Legend and the Enigma by Shoma A Chatterji, published by Harper Collins, looks at Sen as the quintessential working woman, who effortlessly portrayed the dedicated professional woman in many of her films, someone who attempted to create a balance between the demands of love and romance and work.

Within Bengali cinema, traditional gender roles and a renewed emphasis on the value of the home contributed to what might be called a ‘domestic revival’ in the mid-1950s. Suchitra Sen was a product of this time and was a living celluloid evidence of sexist gender representation in the films that saw her rise to the top. But looked at in retrospect, if one were to look closely enough, one could perhaps be able to discover finer arguments within the narrative and the characterization of the leading lady that supported a woman’s right to choose the way she wanted to lead her life.

If she sacrificed her terms for her love for a man such as in Harano Sur, that too was her choice. If she refused to abort her unborn child because she was not married in Hospital, she did that, too, and led the life of a single mother, supporting herself and her son with her earnings as a qualified doctor.

Therefore, even within the framework of a strongly patriarchal ideology, the films of Suchitra Sen were not degrading to women and by and large, beneath the surface, tried not to reinforce patriarchal values.

Courtesy: Subhash Chheda

The dignified persona of Suchitra Sen, on screen and off it, helped uphold the dignity of a woman even when she was a courtesan in Uttar Phalguni.

Any film about a woman in equal partnership with the man she loves—be it her husband or her lover—in strength, intelligence and independence, would not have been accepted by the audience in the 1950s through the ’60s and ’70s in Bengali or Indian cinema. In spite of the optimistic image, it would not have reached the audience because it would have seemed foreign, and somewhat unacceptable at the time.

Looked at from this point, it becomes interesting to read some significant films of Suchitra Sen against the grain, trying to show that she is as independent and as modern as today’s women are, though she fits into the moral and socially acceptable framework for women at the time. Her arrival in Bengali cinema predates the time-space paradigm of feminist readings of Indian cinema. Yet, her films taken together form a focal point.

The term ‘working women’ specifically refers to women whose work is economically productive and involves exchange value in cash or kind or both.

In this sense, the term would apply to the courtesan in Uttar Phalguni as much as it would apply to the single mother who works to bring up her child in Hospital.

Courtesy: Subhash Chheda

‘Working women’ would refer to the widest range of economic and productive activities from a nurse in a psychiatric ward in Deep Jele Jai, to a sex worker in Mondo Meyer Upakhyan (2002) or a saleswoman as in Satyajit Ray’s Mahanagar (1963).

There are at least three terms, namely female participation in labour market, labour force and workforce, which are used interchangeably while analysing women’s participation in economic activities. These terms are indeed related, but denote different dimensions. … Notwithstanding the significance of unpaid work, paid work is associated often with certain characteristics, mainly immediate economic rewards and hence associated decline in economic dependency together with social recognition and standing, which are considered to be critical inputs to women’s empowerment and well-being. Paid work has, therefore, attained some prominence in the policy discourses on gender and development in the South Asian region, where social norms, religious practices and legal entitlements restrict or deny women’s access to, and their claims on familial, economic resources.

Before embarking on an analysis of Sen’s representation on screen as a working woman, one may point out that Suchitra Sen was a working woman right through her adult life that spanned nearly three long decades. One does not quite know at first hand whether there was some intercutting between her real life as a working woman and her screen roles as working women.

One is, however, aware that she slowly became a single working mother to her daughter along the way during her career after her separation from her husband and after his demise.

She was independent in the sense that she made her own decisions about her career choices and on how she would bring up her only child Moon Moon Sen. But this very ‘independence’ also vested her with the financial, emotional and social responsibility of running her family alone, all by herself. According to her close family members, including her daughter, she was against her daughter joining films. Her emphasis was on a strong and solid foundation in education which she herself did not get but ensured that her daughter did. But when her daughter joined films after she was married and became a mother, Sen could do nothing about it and refrained from interfering.

Sen has portrayed the working woman in several films opposite Uttam Kumar. Notable ones among them are Indrani, Harano Sur, Saptapadi, Sabar Uparey, Haar Mana Haar, etc. But in most films where she was paired with Uttam Kumar, the ‘working woman’ identity was almost rendered invisible in the narrative except in two major films, Indrani and Harano Sur. …

The films in which she played a single working woman chosen here include Deep Jele Jai, Hospital, Uttar Phalguni/Mamta and Aandhi.

Source: Facebook

These films do not necessarily back feminist readings of the texts because the female protagonist is not a slogan-raising, flag hoisting feminist by any stretch of imagination. However, she is a working woman, and the protagonist’s working life is presented in different manifestations in these four films.

It is not accidental that she was repeatedly cast as a dedicated professional woman in many of the films—doctor, teacher, nurse—committed to her work and attempting to create a balance between the demands of love and romance and work. So if she is the ‘mahanayika’, that stature is hers not because she compromised on her values and morals, but because she had the conviction to reach the top without resorting to easily available publicity stunts and negotiating her position and status. The contours of this model of stardom successfully deployed a certain image of this modern young woman/star who performs and enacts both tradition and individuated desires.

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter (@thebetterindia).

If you found our stories insightful, informative, or even just enjoyable, we invite you to consider making a voluntary payment to support the work we do at The Better India. Your contribution helps us continue producing quality content that educates, inspires, and drives positive change.

Choose one of the payment options below for your contribution-

By paying for the stories you value, you directly contribute to sustaining our efforts focused on making a difference in the world. Together, let’s ensure that impactful stories continue to be told and shared, enriching lives and communities alike.

Thank you for your support. Here are some frequently asked questions you might find helpful to know why you are contributing?

This story made me

-

97

-

121

-

89

-

167