At Age 64, She Adopted Her First Orphan. And Then Her Story Began.

Thousands of orphaned children in India never find loving homes because the authorities take too long to declare them ‘free for adoption.’ By the time they can be legally adopted, they have grown, and prospective parents in search of newborns pass them over. Prabhavati Muthal, 79-years-old and mother of to two adopted orphans herself, has been fighting to get justice for these children all her life.

Thousands of orphaned children in India never find loving homes because the authorities take too long to declare them ‘free for adoption.’ Prabhavati Muthal, 79 years old and mother of two adopted orphans herself, has been fighting to get justice for these children all her life. We appeal to all our readers to support her by signing her petition.

“We are guilty of many errors and many faults, but our worst crime is abandoning the children, neglecting the fountain of life. Many of the things we need can wait. The child cannot. Right now is the time his bones are being formed, his blood is being made, and his senses are being developed. To him we cannot answer ‘tomorrow,’ his name is ‘today’.”

― Gabriela Mistral

“Aai tu Aai saarkhi nahi disat, Aaji sarkhi diste. Mala ‘Mummy Papa’ hawa aahe”

(Mom you don’t look like a mom, you look like a grandma. I want my Mummy Papa!)

Mohini often used to say this to Prof. Prabhavati Muthal. Mohini was 5-years-old now and she had heard from her schoolmates that she had not come out of her mother’s womb but from a dirty sack, and because of that, her right arm was paralyzed.

Photo Credit: Tawheed Manzoor/Flickr

On November 30, 1996, Prof. Prabhavati Muthal had retired and was all set to relax for the rest of her life in Chandrapur, Maharashtra, after working for 35 years as a history professor. Her son was a well-known paediatrician at the local government hospital.

There was no orphanage in the town. Thus, unwanted and orphan (mostly newborn) babies landed in Dr. Muthal’s ward. Like all government hospital wards, this too was crowded. The nursing staff were always overloaded.

On March 30, 1997, a lady sarpanch from a nearby village brought a brutally battered newborn girl to Dr. Muthal. The baby was just 3 days old. She had been tied in a gunny bag and thrown in the garbage to die. Someone had found her and informed the sarpanch.

The girl was visibly injured. Her skull was fractured. Yet, for three days, the lady sarpanch had not provided her with any treatment nor had she informed the police. Consequently, the child became critically sick, developed a high fever and started convulsing.

Even then, the lady was reluctant to let the hospital keep the child and treat her. Dr. Muthal had to threaten her and force her to admit the child to the government hospital. On seeing how serious the child’s condition was, the lady sarpanch disappeared from the scene.

For weeks, the child hovered between life and death. One usually associates government staff with impersonal and callous behaviour, but the nurses at this government hospital rallied together to save the child. One of the sisters told Dr. Muthal: “God will not forgive us if we cannot save this child.”

Due to their untiring efforts, the child survived. But the prolonged battle for life had taken its toll. She was badly emaciated and cranky due to constant pain. She had major neurologic deficit, which left her right side paralysed. Feeding and cleaning her was an ordeal.

Prof. Prabhavati Muthal willingly took over this daunting task. With her selfless love and care, the child gradually improved. As she grew healthier, a beautiful face emerged. She looked so attractive that she was called ‘Mohini.’

Her story attracted a journalist’s attention and she became well known. Many people, including a doctor, came forward to adopt her. Suddenly, the lady sarpanch re-entered the scene and demanded custody of the child.

The custody of orphan children is decided by the JWB or Juvenile Welfare Board (the name for the Child Welfare Committee before the year 2000). To everybody’s surprise, the local JWB gave Mohini’s custody to the same sarpanch, ignoring better claimants and the lady’s past suspicious behaviour.

Alarmed, Prabhavati approached the Sessions Court. After a prolonged struggle lasting over 2 years, the Sessions Court finally overturned the JWB’s order.

Prabhavati then decided to establish an orphanage so that Mohini had a place to stay. The orphanage, called Kilbil (chirping of birds), is now 16 years old.

However, Mohini’s agony did not end here. The infuriated JWB avenged the situation by blocking her transfer to the orphanage for a year. Finally, her case was cleared by special order of the state government. The JWB continued to obstruct her rehabilitation. She was finally declared ‘free for adoption’ by the Session Court under section 7.3 of the Juvenile Justice Act after one more year.

‘Free For Adoption’ means that a child’s parents or guardians have relinquished their parental rights or have had them terminated in a court of law. Once this has occurred, a child is then ‘legally free’ to be adopted by another person or family member. Any orphan or abandoned or surrendered child, declared legally free for adoption by the Child Welfare Committee (CWC), is eligible for adoption.

“Most of the couples prefer small babies so that they can enjoy each milestone of the baby while growing up. If a child is not made ‘free for adoption’ soon, then mostly they don’t get adopted and lead an affectionless life,” says Prabhavati Muthal.

Unfortunately, in Mohini’s case too, all the prospective adoptive parents had given up by the time she became ‘free for adoption.’ No one was willing to wait for years and fight court battles just to adopt a physically impaired child.

When nobody came forward to adopt her for more than a year, Prabhavati decided to adopt Mohini herself and become a mother to a 4-year-old child at the age of 64.

Kilbil had now become the home of many abandoned children. Vasundhara (Vasu) was one of them. Just a few days old, Vasundhara was found in one of the movie theatres of Chandrapur. She did not have one ear. Every adoptive couple wanted a beautiful and flawless child and so did not adopt Vasu. It was Vasu’s 11th year in Kilbil. She was supposed to go to a remand house for juveniles once she became 12. Prabhavati couldn’t let this child go and so, once again, she took the legal guardianship of Vasundhara.

Vasu and Mohini are sisters with the same mother now!

At the time that Prabhavati was looking to adopt Mohini, the law required that to contest a case, you must be the ‘aggrieved party.’ This means you should be affected somehow by the case — it is only then that you have the ‘locus standi,’ that is, eligibility to participate in the judicial dispute.

Prabhavati had none, but she could participate in the dispute because lawmakers then (1986 version of the Juvenile Justice Act) had wisely put in Sec 7.3, which said:

“The powers conferred on the board or juvenile court by or under this act may also be exercised by the high court and the court of session, when the proceeding comes before them in appeal, revision or otherwise.” – Juvenile Justice Act 1986. Sec. 7.3 Chapter II

The word ‘otherwise’ opened the window for any conscientious citizen to seek redress from the Sessions Court purely on merit of the case, bypassing technicalities like ‘locus standi.’ The same clause also allowed the Sessions Court to declare Mohini ‘free for adoption.’

It is vital to keep this window open for the orphans, because they have no one to look after them. The orphanages that keep the children and the parents who adopt the children are really ‘beneficiaries’ and not truly ‘aggrieved.’ They have no real stake in any individual child.

The only victim of a wrong decision (or lack of decision) is the orphan child. The child is therefore, the only truly ‘aggrieved. ’

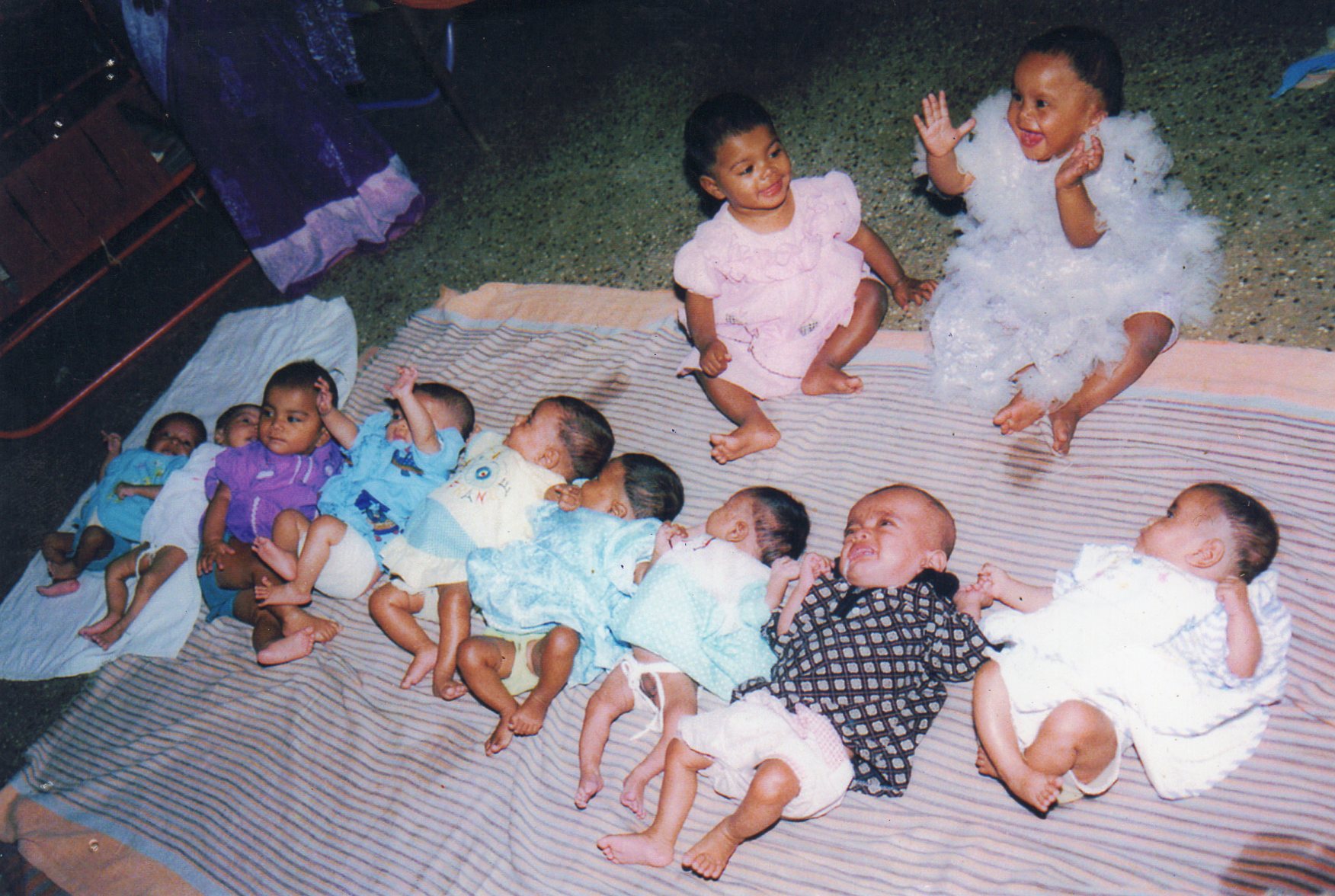

Picture for representation. Credit: J P Davidson/Flickr

Unfortunately, this Section was deleted only for orphan babies in the newer editions of the Act. The implications are tremendous for the orphan children, because now the CWC has absolute power over orphan children. There is no effective, accessible mechanism to correct its mistakes, misdeeds and inaction.

Please help Prabhavati make a representation to the government authorities to suitably amend the Juvenile Justice Act and include a clause like Sec. 7.3 of 1986 Juvenile Justice Act in the present Bill for orphan children by signing this petition.

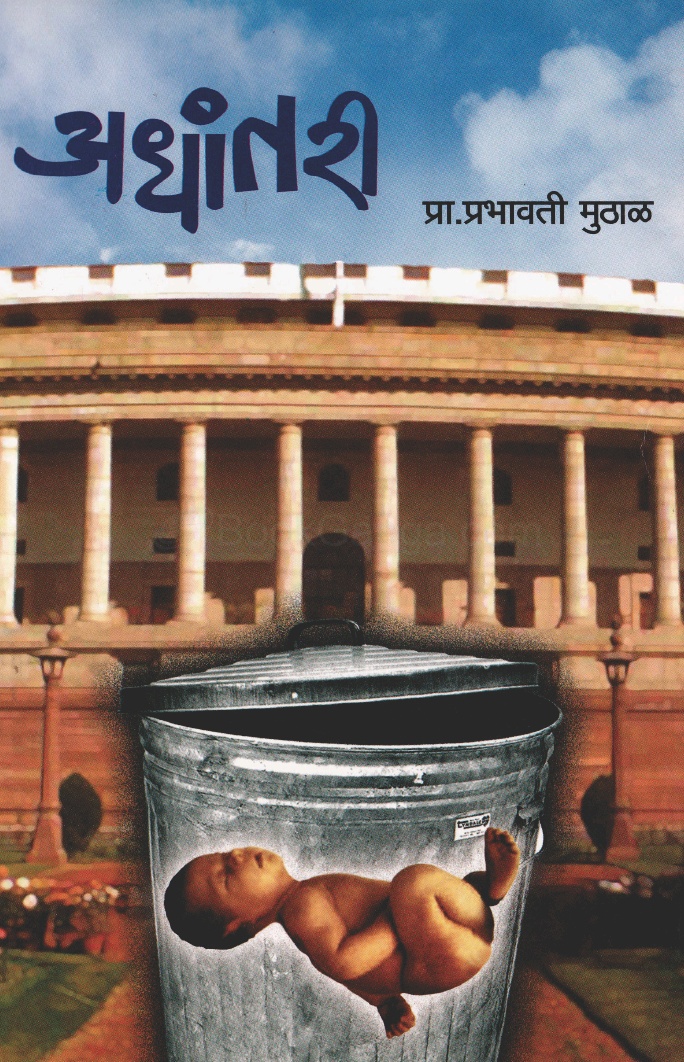

Prabhavati has also penned the story of her struggle in a book titled Adhantari. This book has bagged an award from the Maharashtra government.

If you wish to help Prabhavati in her struggle for justice for these kids, or wish to donate for Kilbil, please email at [email protected]. You can buy Adhantari (the book is in Marathi) by writing to the same email address. Prof. Muthal is also looking for writers who can translate the book into English.

Like this story? Or have something to share? Write to us: [email protected], or connect with us on Facebook and Twitter (@thebetterindia).

This story made me

- 97

- 121

- 89

- 167

Tell Us More

We bring stories straight from the heart of India, to inspire millions and create a wave of impact. Our positive movement is growing bigger everyday, and we would love for you to join it.

Please contribute whatever you can, every little penny helps our team in bringing you more stories that support dreams and spread hope.